Non-Traded REITs: Go Mainstream or Die

Fundraising for the sector fell in 2016 due to the combination of impending regulatory changes and lackluster performance, notes Yardi Matrix Associate Director of Research Paul Fiorilla. The sector must continue to lower fees and improve liquidity to attract new investors.

By Paul Fiorilla, Associate Director of Research, Yardi Matrix

Improving transparency and liquidity, as well as lowering fees, are at the top of the to-do list for the non-traded REIT market in 2017, challenges that will force the industry to transform and usher in new ways of doing business and new types of sponsors.

Improving transparency and liquidity, as well as lowering fees, are at the top of the to-do list for the non-traded REIT market in 2017, challenges that will force the industry to transform and usher in new ways of doing business and new types of sponsors.

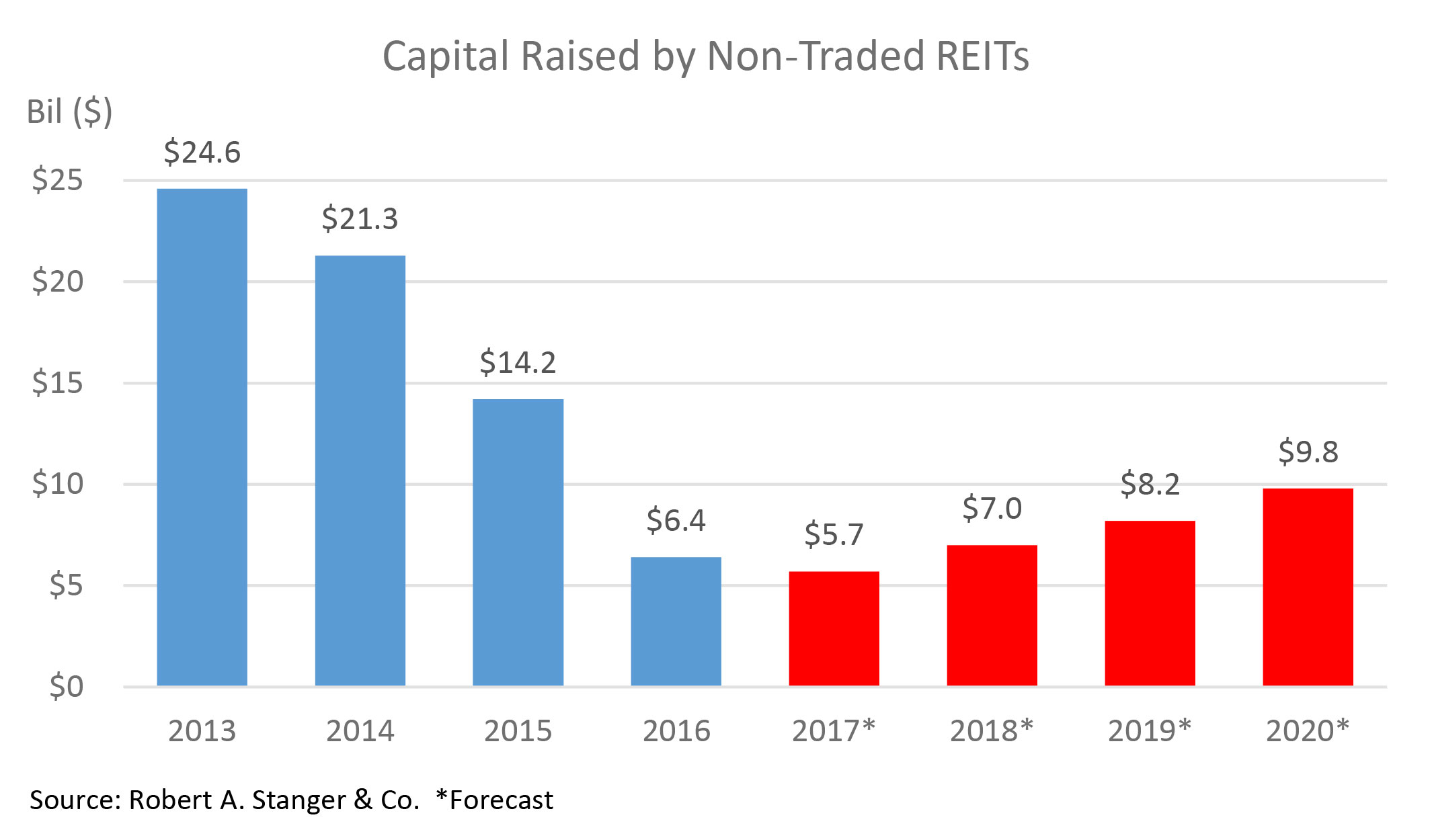

Fundraising for the sector—which began to decline in 2013—plummeted dramatically in 2016 due to the combination of impending regulatory changes and lackluster performance of the sector. Non-traded REITs attracted only $6.4 billion in 2016, down nearly 75 percent from the $24.6 billion raised in 2013, according to Robert A. Stanger & Co.

The situation could get worse before it gets better. Stanger CEO Kevin T. Gannon, speaking at the IMN Non-Traded REIT & Retail Investment Symposium in New York last week, forecast capital raising to decline further to $5.7 billion this year. Another ominous sign came last week, when industry leader W.P. Carey announced it was exiting the non-traded REIT business after more than 40 years to focus on its net-leased real estate portfolio.

New regulations have played a big role in the sector’s demise. One is the Department of Labor’s “fiduciary rule,” which went into effect in June after being delayed by the new administration, and requires investment advisors to justify the high fees they charge retail investors. Another is the Securities and Exchange Commission’s Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) 1502, which requires broker-dealers to provide investors with a fair estimated value of their holdings.

The new regulations have made the traditional broker-dealer network reluctant to steer clients to non-traded REITs. Brokers complain that they don’t get properly compensated, the rules are vague and they don’t protect them from litigation. But that’s just a part of the industry’s problems. Investors are turned off by high fees and illiquidity, and performance has been weak. Gannon said returns for non-traded REITs were 5.6 percent in 2016, compared to 9.6 percent for private real estate and 12.0 percent for the S&P Index.

Outdated fee model

Non-traded REITs are lowering fees, but they still have a long way to go. The traditional model relied on brokerage networks marketing shares to individuals that were seeking high dividends at a fixed share price. The total load for investors was 11 percent to 12 percent, or more. Investors who put $1,000 into a non-traded REIT would thus have $880 in their accounts at the start. But investor statements focused on the original amount of the investment, not the current value.

FINRA rule 1502, which went into effect a year ago, contributed to the fundraising malaise. Speaking at last week’s IMN symposium, FINRA Vice President Paul Matthews said he was not happy to see the industry struggling, but he said it would be in worse shape without the disclosure.

“From our perspective, it is good to see changes in product structure,” he said.

Non-traded REITs are adopting new fee strategies, which have dropped the up-front load. A few new offerings have eliminated up-front fees, while older vehicles still charge around 8 percent for new capital raised. In any event, market players recognize that fees generally remain too high to attract much capital when competing against products with lower fees such as listed REITs or mutual funds. Broker-dealer networks have little incentive to sell the product without the fees they had been getting, and sales from that source have hit an all-time low. Non-traded REITs are left with unpalatable options that include deferring the fees, absorbing the cost of marketing, or raising capital in a different manner.

New York-based W.P. Carey’s decision to exit the non-traded REIT sector rested in part on the high cost of employing a broker-dealer network and the inconsistency of raising capital through retail channels. Mark J. DeCesaris, W. P. Carey’s CEO, noted that the firm looked at structures and products that would be necessary to compete under current market and regulatory conditions.

“Our conclusion was that our shareholders would be better served by focusing on our core net-lease investment expertise,” he said.

Institutional Future?

The fundraising conundrum has opened the door for the participation of institutional sponsors that can raise money independently of broker-dealers and/or have the internal infrastructure to support the cost of capital raising. Institutional firms that include JLL, Cantor Fitzgerald and RREEF are among the players moving into the space. But it is investment giant Blackstone that is lapping the field with a perpetual non-listed REIT targeted at individual investors. Blackstone Real Estate Income Trust, which aims to raise $5 billion, has so far raised about $700 million, or roughly 40 percent of the capital raised by all non-listed REITs to date in 2017.

Besides lowering fees, non-traded REITs also must improve liquidity and transparency. The old model was a closed-end fund in which the share value was unknown until the liquidity event at the end of the investment period, in which case investors were often surprised that the share price was far below par. Non-traded REITs are developing NAV funds that are priced daily or quarterly, which makes them easier to trade. Non-traded REITs also are working on being more transparent and providing more information to investors during the life of the vehicle.

The upshot is that the industry has no choice but to adjust. Fees must be commensurate with competing products. Sponsors must provide features, such as liquidity and transparency, which are available to investors of mainstream securities. And the market must produce competitive returns and better sponsors, avoiding the management conflicts of interests and accounting scandals that periodically occur.

No Going Back

There are questions about whether regulations such as the fiduciary rule or FINRA 1502 will be rolled back by the Trump administration or Congress, but even if that happens, few expect the market to return to the way it was.

“Even if the (fiduciary rule) doesn’t get implemented, the industry is taking a little different view, a little self-introspection of itself, saying ‘you know what, we have to change the way people perceive us and we have to change our fees differently and we have to act a little differently,’ “ Gannon said in a recent interview for the “Focus on Alternatives” video series produced by Real Assets Adviser magazine. “Even if that rule doesn’t go into effect, we’re all better off if we have the investors best interest at heart.”

Some in the industry are optimistic that changes, though painful now, will ultimately be good for the industry. The idea is that a sector with well-capitalized sponsors and products with quality structures will attract investors and create space for a growing number of sponsors. The potential is large, as accredited individual investors have an estimated $45 trillion in net worth.

Stephen Hamrick, president of Terra Income Funds, a debt platform, noted that mutual funds once were a high-fee product that was considered as an alternative investment.

“The advent of ongoing pricing and periodic liquidity will provide the opportunity to expand to a significant portion of folks that are not invested in the industry,” Hamrick said. “That will enable the sector to get out of the box it is in and become more mainstream.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.