Interest Rates and The End of Quantitative Easing

Real estate investors should prepare for volatility in interest rates and asset values over the next few years, suggests CBRE Vice President Brandon Smith.

By Brandon Smith

After amassing close to $4.5 trillion of assets in the years after the global financial crisis, the U.S. Federal Reserve is signaling that it will begin trimming its balance sheet before the end of this year.

After amassing close to $4.5 trillion of assets in the years after the global financial crisis, the U.S. Federal Reserve is signaling that it will begin trimming its balance sheet before the end of this year.

This balance sheet reduction will likely happen slowly, but its effect on interest rates could be significant. Two months ago, some analysts believed the 10-year Treasury would rise to 2.75 percent or higher by the end of this year. However, given that the 10-year Treasury dropped to 2.07 percent the day after Labor Day, the aforementioned projection looks very unlikely. The impact of a balance sheet reduction remains unknown—mainly because this is the first time any government has tried this. But, given the sheer volume of assets, the impact could be moderate to severe.

The key question for anyone in commercial real estate: what happens to your business with LIBOR at 2.0 percent to 2.5 percent, and the 10-year fixed-rate loans sizing at 4.50 percent to 4.75 percent (compared to 3.8 percent to 4.0 percent today)?

How does quantitative easing affect interest rates?

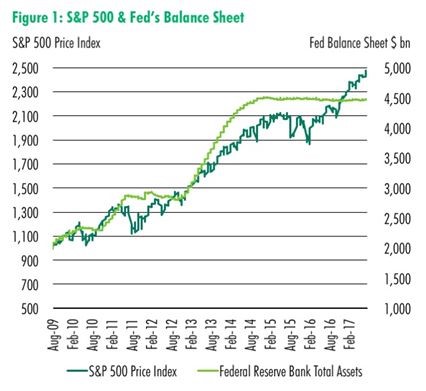

The increase of quantitative easing (QE) has been followed by an appreciation of global asset prices (see Figure 1). The hawkish economists use this relationship to emphasize that QE is propping up the stock market. But correlation does not imply causation—and even if it did, how does this apply to commercial real estate and interest rates?

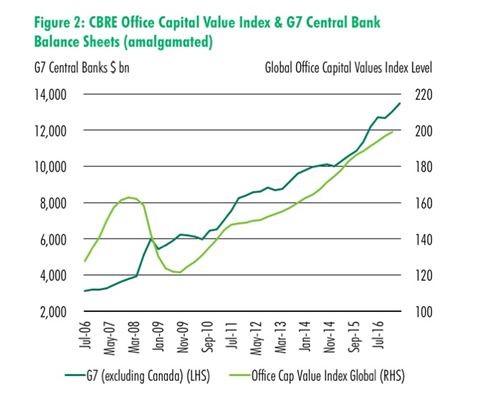

Let’s compare the aggregate balance sheets of the G7 central banks to CBRE’s index of global capital values (see Figure 2). A strong correlation is also apparent. Both of these charts clearly illustrate why the market panics any time a central bank representative talks about raising rates or reducing or eliminating QE. Just Google “Taper Tantrum 2013” for a quick example. Any hint of removing QE has caused stocks to drop, interest rates to spike and property cap rates to increase.

The next question is: once the market loses its crutch, what happens? Don’t worry, it’s not death and destruction because a few things are different from nine years ago.

First, global growth is self-sustaining. QE was an emergency policy the Fed used to “do whatever it takes” to maintain growth. Figure 1 shows that the S&P 500 has now unhitched itself from the central bank’s balance sheet. This is good news for investors and my 401(k).

Second, economic growth is continuing, but it’s not robust. The economy fell short of expectations in August, adding only 154,000 jobs compared to an expected 180,000. Earnings growth remains stagnant at 2.5 percent and has been falling since February. Lastly, the Core PCE—the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation—is only at 1.4 percent. Core CPE has been below 2.0 percent since April 2012, and has been trending downwards over the past 12 months. All of this means that economic indicators will have downward pressure on rates.

Third, uncertainty and volatility at the political level creates a great environment for low rates. The robust economic agenda of infrastructure spending and ending Obamacare has stalled. Congress currently faces a full task list that includes immigration reform, building The Wall, tax reform, emergency hurricane response spending, raising the debt ceiling, and keeping the government open. The odds are low that Congress passes anything meaningful. Plus, North Korea’s saber-rattling sends investors to the safe haven of bonds. Unless there is an aggressive economic agenda with bi-partisan support, inflation won’t increase due to actions in Washington.

Lastly, central bank balance sheets are still expanding globally, with the ECB and Bank of Japan still pursuing QE. However, that may change before the end of the year: look for the ECB to make a specific statement at its October meeting.

Real estate investors would do well to prepare for near-term volatility in rates and asset values—probably over the next 12 to 36 months. Without signs of stronger growth, higher inflation, political will and world peace, rate volatility will be somewhat muted and therefore any imminent fear is unfounded. Nevertheless, as we’ve seen from many of our clients, it is wise to take advantage of historically low rates and refinance assets when possible.

You must be logged in to post a comment.