ULI Europe: Making Cities Livable

Building on the examples of Vienna and Paris, speakers at the 2021 ULI Europe Conference share the importance of investing in urban development.

What exactly goes into making a livable city and what role does urban infrastructure play? At the virtual 2021 ULI Europe Conference Urban Infrastructure/Transit Orientated Development Forum, speakers Maria Vassilakou and Marc Lhermitte touched on the topic from the perspective of two major European cities—Vienna and Paris. The conversation was moderated by Tom Daamen, associate professor in urban development management at Delft University of Technology.

The Vienna Model

Maria Vassilakou, the first green vice mayor of Vienna and founder of Vienna Solutions, now working worldwide as an independent advisor on urban transformation, shared why Vienna is constantly improving its position within global rankings for livable cities. Urban design—which once meant technical, heavy infrastructure—currently draws on the historical lessons paired with well-established strategies focusing on quality and affordability. Or, in Vienna’s case, “preserving maximal quality of life for everybody … by minimal consumption of resources and by using innovative solutions,” Vassilakou explained.

Vienna’s smart city framework has been in the works for decades now and the key to success is a combination of elements such as new technology, a sustainable transportation network, placemaking, green infrastructure and affordability. Public housing, along with technical and social innovation and cooperative governance, are the main factors behind Vienna’s positive results. An effort that began a century ago, social housing has grown into an annual investment exceeding $700 million. Currently, 62 percent of the Viennese population already lives in public or subsidized housing units and pays affordable rents. And according to more recent regulations, new neighborhoods must include two-thirds of subsidized housing.

When it comes to urban development in Vienna, a city that gains some 25,000 residents per year, authorities partnered with developers and citizens in creating a healthy and safe environment for the residents while also focusing on affordability and sustainability, as new projects are required to follow specific energy zoning.

READ ALSO: ULI Europe Showdown: The Future of Office

One of the main purposes in creating urban quarters is eliminating the need to relocate to the suburbs, and thus avoiding lengthy commutes. But urban development also comes with challenges related to increased density, which calls for vertical housing as a viable solution. While some reluctant residents deem anything higher than two stories “a monster building”, project acceptance and resident contentment can be achieved by involving citizens in negotiations and the design process—in other words, cooperative leadership.

Urban quarters also bring economic development for Vienna. The Main Railway Station, a $1.2 billion development project that stretches across 270 acres, includes a transportation hub, a business district home to some of the largest Austrian banks, as well as a residential area with 5,000 units, a 17-acre park, a school campus, a 3.4-mile network of new streets and pedestrian bridges over the rails. In line with Vienna’s dense and green philosophy, the development doesn’t feature any fences or gated communities, ensuring 24/7 access to everyone, not only residents who live within the quarter.

About 50 percent of Vienna encompasses green spaces. The city’s newly built parks are connected to existing green areas through green boulevards, ensuring accessibility to every resident. Furthermore, Vienna achieved its “five-minute city” status through enhanced transportation options, which must be present before the first residents move in, according to Vassilakou. In fact, the city’s philosophy is that all newly built urban quarters must provide high-level access to public transportation.

Grand Paris

Marc Lhermitte, a partner in the EY consulting practice and the global leader of International Location Consulting Services, has been involved in the Grand Paris mega-project since 2008. As the largest infrastructure project currently underway in Europe, Grand Paris has an estimated cost of nearly $51 billion and is expected to decongest the Paris core area. Société du Grand Paris and Métropole du Grand Paris are the key authorities behind the massive undertaking, along with multiple stakeholders involved. The funding for Grand Paris comes from public-private partnerships.

“The start of the project came when, at the highest level of Government and also in the business communities (and for) a lot of scholars and architects, it became clear that Paris was losing ground, especially … versus the fast-growing global city called London, thanks to the Olympic ramp-up,”, Lhermitte said, adding that London’s status as a financial services hub and home to technology giants and real estate developments was considered superior to many European cities at the time. However, given the ramifications of the U.K.’s separation from the European Union, Brexit is expected to put a dent in London’s domination and Paris is surely catching up.

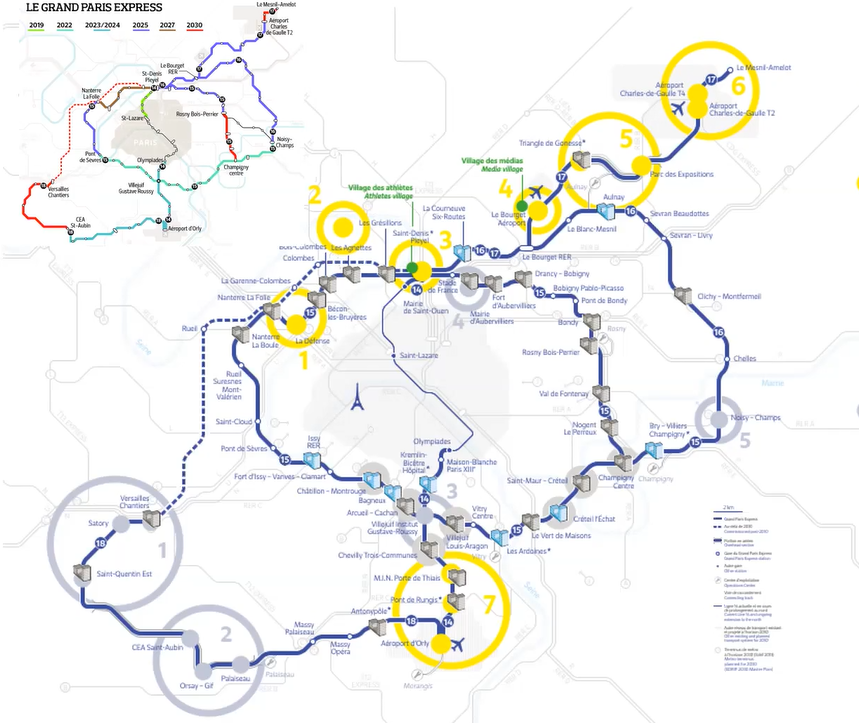

The project, which is still subject to revision, is anticipated to double the metro and rapid transit network by adding some 124 miles of new transportation network and connect communities to the Greater Paris area. Grand Paris Express means innovation in transportation equipment and building a data ecosystem with an emphasis on smart features. Plans call for extending the transit system with the addition of 68 new stations and seven major urban hubs, which will include housing, office and commercial space.

READ ALSO: How TODs Are Bringing People Back to Public Transit

One of the major pain points in France is the gap between housing demand and supply, and Grand Paris intends to address the issue with an elaborate strategy in place, as developers plan to build 70,000 new homes per year. Another challenge for Paris is the fact that, unlike Vienna, population growth in the region has been sluggish and the city still has a ways to go in terms of reducing the social divide, which is also among the project’s purposes. Furthermore, Grand Paris aims to maintain Greater Paris’ position among global cities, attract investment, restore balance in spatial organization and environmental fragility in the region as well as bolster employment.

So, from a big-picture perspective, what does the future hold for French economic policies? According to Lhermitte, a strong focus on improving regulation and lowering taxes is fundamental in driving change and growth. Additionally, when asked what a post-pandemic future and recovery looks like, Lhermitte said that society will not bounce back to pre-pandemic behaviors anytime soon, as people have developed new habits that may be here to stay in the long-term.

You must be logged in to post a comment.