Analysis: How Biden’s Tax Plan Would Reshape CRE Investment

All investors will feel the impact of some of the changes, but commercial real estate could be hit particularly hard, experts say.

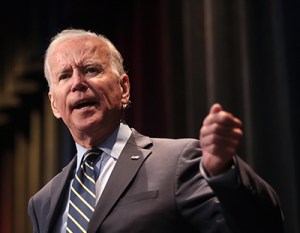

President Biden called on Congress to make tax code changes this week that could hurt commercial real estate investors’ pockets. But the code changes detailed in The American Families Plan could also result in fundamental shifts in how real estate is bought, sold and developed.

One of the major themes of the president’s campaign as well as his first 100 days in office has been equity. Instead of raising taxes on middle-class Americans to pay for the plan’s $1.8 trillion in spending, he is setting his sights on high-earning investors and real estate investors, in particular.

In the real estate industry, he is taking aim at two tax incentives that are baked into a tremendous number of real estate deals: 1031 exchanges and carried interest for private equity fund managers.

“The administration is looking for ways to limit disparity and the wealth gaps we have in this country—the sort of K-shaped economy that we are emerging into more and more that existed before the pandemic but has been exacerbated by it,” said Bradley Tisdahl, CEO of Tenant Risk Assessment. “But it would dampen a lot of the upside for folks of inheriting wealth and making money through investment as opposed to through work.”

1031 Exchanges

1031 exchanges are used in all property types and across the real estate investor universe. Biden is asking Congress to enact legislation that would disallow 1031 exchanges for gains greater than $500,000.

“A lot of 1031s are over the limit of $500,000,” said Jonathan Hipp, principal & head of Avison Young’s U.S. net lease group, “and on the private capital side, they are all going to be above that $500,000 capital gains.”

READ ALSO: The Benefits of Section 1031 No One’s Talking About

Meanwhile, Biden has proposed raising the long-term capital gains tax rate from 20 percent to 39.6 percent for investors with incomes over $1 million.

“It’s a very upsetting proposal for the real estate industry,” said Robert Gilman, co-leader of the Real Estate Group at Anchin. “I think everyone was under the thought (that) tax rates were going up—both capital gains and ordinary rates—but this is a double hit against the industry.”

Without the 1031 exchange option, someone who buys a property for $5 million and sells it for $15 million no longer has $15 million to re-invest, Gilman explained. Instead, that investor will be paying 40 percent federal tax plus other taxes that could add up to 50 percent of the gains from the sale. That would leave them only $10 million to reinvest.

If Congress moves to severely limit 1031 exchanges, experts say, there is likely to be an initial rush to sell properties held in 1031 before the change takes effect. That will probably be followed by a drop in the number of property sales transactions and less liquidity in the market.

“At the end of the day, incentives add investors to real estate, and now you are doing something that has a potentially negative impact on buyer pools,” said Preston Young, national head of office investor services for Stream Realty Partners, a real estate services and investment and development firm.

Carried Interest

The carried interest benefit plays a role in every private equity investment. Carried interest is the fund manager’s share of the profits, when the profits are realized, and it amounts to the bulk of a fund managers’ compensation. It is designed to align the manager’s interests with the investor’s and to incentivize performance.

Under the current tax code, carried interest is considered return on investment, so it is taxed at the 20 percent capital gains rate rather than the 37 percent regular income tax rate, for those who make over $1 million.

READ ALSO: What You Need to Know About Taxation, Valuation in 2021

If Congress approved Biden’s proposal, carried interest would be taxed at the regular income tax rate, which Biden has proposed increasing to 39.6 percent for those earning more than $1 million.

As a result, fund managers may need to find new ways to structure fees and to allocate the increased cost due to the change in carried interest classification.

“Now, that just shifts a lot of business plans that may not be viable when you can’t capitalize on the gains tax cap,” said Young.

But if Biden manages to raise the long-term capital gains tax to 39 percent for all investors, the carried interest change is actually canceled out anyway. “It’s almost moot,” said Gilman.

Biden’s plan would also eliminate the step-up in basis for properties and other assets that are inherited. Currently, the basis on a property that is passed on to heirs is stepped up to fair market value at the time of death. The heirs, therefore, pay no tax on any appreciation in value since the asset was purchased because, technically, there is no gain. Take, for example, a property purchased at $1 million that was worth $10 million at the time of inheritance. Under the change, the estate would have to pay capital gains tax on the $9 million gain, Gilman said.

The Fight Continues

Last month, more than 30 trade organizations signed a letter to Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen extolling the positive effects that like-kind exchanges have throughout the economy. The groups will continue their lobbying while Congress debates Biden’s tax proposals and structures them into law.

Jamie Woodwell, vice president for commercial and multifamily research at the Mortgage Bankers Association, said it is too early to tell what shape the tax changes could take, but the effects on liquidity could be decisive.

“Commercial real estate is probably one of the most capital-intensive industries there is,” said Woodwell. “So any time you start talking about the way that capital is taxed, you are talking about things that could have a significant impact on investment in the sector.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.