Inflation Fears and Commercial Real Estate

Are the 1970s comparisons overblown? A deep dive into what to expect from Yardi Matrix Research Director Paul Fiorilla.

While the U.S. economy has produced its highest growth in decades, much of the economy-related attention is focused on inflation, which not coincidentally is also running at its hottest level since the 1980s. Are the worries justified, especially for real estate?

Qualms about inflation are typically couched in terms of whether it will spiral out of control and prompt the Federal Reserve to act to reduce growth that leads to a recession. That scenario is based on the experience of the last sustained bout of inflation in the 1970s and early 1980s, but there are important differences between the economy of that era and today that are likely to mitigate the likelihood of “stagflation.”

In any event, whether high inflation is a problem for commercial real estate is another question. A recent study by Greg MacKinnon, research director of the Pension Real Estate Association, found that commercial real estate performance has been good during periods of high inflation and that returns are much more closely correlated to growth than inflation.

READ ALSO: CRE Applauds $1.5T Infrastructure Plan

“The lesson for today’s real estate investors trying to interpret what the macroeconomic environment means for real estate is that overall economic strength is much more important than whether inflation may rise or fall going forward,” the paper said. Or as MacKinnon put it in a recent webinar: “If the economy is doing well, real estate will do well, no matter what happens with inflation. Inflation is not critical in itself for commercial real estate.”

GDP, Inflation Highest in Decades

U.S. GDP is projected to top 5.0 percent for the year, the first time it would reach that level since 1984, when it was 7.2 percent. Inflation growth reached 6.8 percent year-over-year in November, the fastest rate since January 1982, and has been above 5 percent for the last six months.

Growth is good for the economy, and inflation is also considered a positive—up to a certain point. The Federal Reserve sets monetary policy to balance full employment and an optimal level of inflation, which is set at a 2 percent long-term average. Even though the 2 percent number is somewhat arbitrary, given the impact of inflation in the past it is proper to ask whether the current level will persist and inflict longer-term damage on the economy.

The spikes in growth and inflation have been caused by a culmination of events started by the pandemic, the unprecedented halt to parts of the economy and the extraordinary amount of monetary and fiscal stimulus provided by the federal government. Consumer balance sheets have been boosted by roughly $2.7 trillion of additional savings and government stimulus during the lockdown. As cities eased lockdowns in the spring, the combination of pent-up spending, supply chain disruptions, wage increases, and higher energy and commodity prices prompted inflation to soar.

While few expect inflation to recede to the Fed’s target level soon, the prognosis and severity are debated. Optimists say that inflation will gradually ease. In this view, the impact of the stimulus is abating, while energy prices will level off or decline. Meanwhile, the supply chain disruptions are receding, and consumer spending will normalize as the pent-up spending runs its course. Finally, wage growth will moderate as people who left the labor force during the pandemic return and ease the shortage of workers, especially for service jobs.

“In our view, hand-wringing about inflation is both justified and reaching the end of its critical period,” Wells Fargo Bank senior economist Tim Quinlan said during the webinar last week. “While we do (forecast) above-trend growth in inflation for each of the next couple of years, we see the headline rate of inflation coming down perhaps as soon as late in the first quarter (of 2022), certainly by the middle of next year.”

READ ALSO: The Trends Likely to Shape CRE in 2022

Others say inflation may not be so quick to recede. One reason is the rapid growth in housing costs—reflected in the 13.7 percent growth in U.S. multifamily asking rents year-over-year through November, according to Yardi Matrix—which comprise nearly one-third of the CPI. Because of the way housing costs are calculated in the CPI, it can take six months or more to show up in government consumer price index data, which means the rise in housing costs might impact CPI in coming months. To be sure, though, the increase in asking rents only affects vacant units that are released, and rent increases are much smaller for tenants that roll over an existing lease.

It’s also far from clear that the “Great Resignation” is about to reverse—and even if it does, whether that would slow wage gains. Some workers have decided to retire permanently, while others have concerns about health and safety, and still others must care for children or the elderly.

Another inflation concern is additional federal stimulus, which includes the newly passed $1 trillion infrastructure package and a second $1.5 trillion package that is being negotiated in Congress. That leads some to contend that even if growth recedes to the 4 percent range in 2022, inflation may remain at unhealthy levels. “It’s hard to see growth of that kind without (high) inflation,” former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers said during a recent interview.

Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell and other Biden administration officials downplayed the potential of long-term inflation for most of the year, dubbing it “transitory.” However, more recently they stopped using that word, and they are now talking about unwinding the Fed’s $9 trillion balance sheet. While Federal Reserve executives are not commenting on raising the fed funds rate, most observers expect rates to increase starting in 2022 (earlier than previously expected).

Are ‘70s Comparisons Overblown?

Since there is consensus that inflation will remain above-trend through 2023 or later, the debate is centered around how bad that is for the economy and whether it sets off a spiral of negative events. Inflation has been very low for a long time, so a short period of running hot isn’t likely to do any permanent damage. But rising wages and materials costs could prompt companies to raise prices to maintain profits, and if consumers feel pressure and lose confidence, they could stop spending.

If inflation does spiral, it could prompt the Federal Reserve to raise rates sharply and throw the economy into a recession, which happened during the last period of sustained inflation in the 1970s and 1980s. To fight inflation, former Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volker increased the federal funds as high as 19 percent in 1981, prompting two recessions.

READ ALSO: Why Office Absorption Will Turn Around in 2022: NAIOP

There are good reasons to think that the 1970s comparisons are overblown. For one thing, price hikes today remain well below levels in the 1970s and ‘80s, when inflation reached as high as 14.8 percent in 1980. Another dissimilarity is that the economy has generally been strong for years, with interest rates and unemployment steadily declining over the past decade (other than the pandemic). The 1970s inflation had multiple drivers, but the main one was the sharp spike in oil and gas prices set off by the 1973 oil embargo by Saudi Arabia and allied Arab nations, which blocked oil exports to the U.S. and set off years of gasoline shortages. Domestic oil production has grown dramatically, and the U.S. is not at the mercy of foreign producers as it was in the 1970s.

What’s more, the U.S. economy is more diverse and resilient than it was in the period leading up to stagflation. The technology industry, which today is the most vibrant sector of the economy and has companies with the largest employment growth and market capitalizations, was barely a glimmer in the 1970s. For all those reasons, the comparisons with inflation in the past seem overblown.

Is CRE a Hedge Against Inflation?

Commercial real estate is commonly believed to serve as a hedge against inflation, because rents and values tend to rise in an inflationary environment. This simplistic formulation, however, doesn’t consider other negative impacts of inflation on the economy.

To test the theory about inflation, the PREA study looked at total returns of properties in the NCREIF Property Index, which comprises core properties owned by institutional managers. The study calculated returns between 1978 and 2020 through periods of low, medium and high GDP and inflation growth. The study found that returns were the highest in periods of high growth and low inflation, but that growth was a much more relevant factor for performance than inflation.

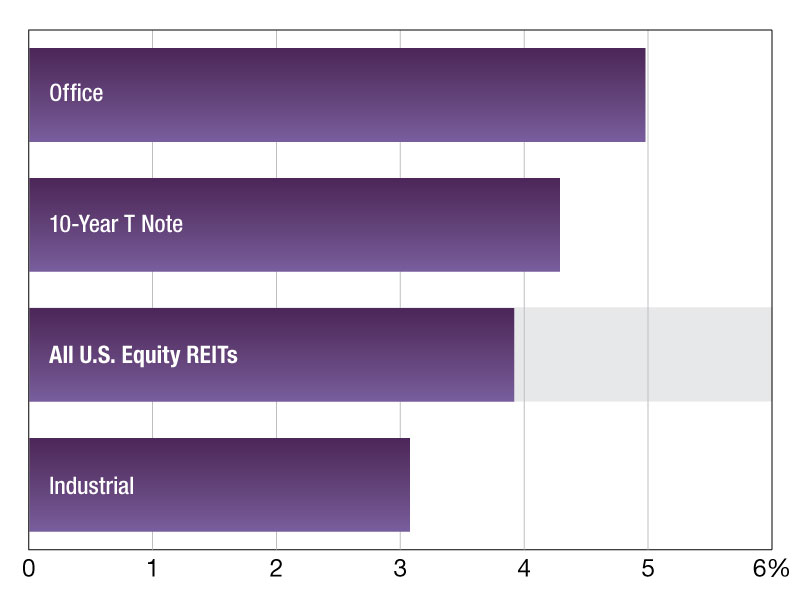

NPI returns averaged 9.3 percent during periods of high inflation, 10.1 percent during periods of medium inflation and 7.2 percent during periods of low inflation, the PREA study found. NPI returns averaged 12.6 percent during periods of high GDP growth, 9.9 percent during periods of medium growth and only 4.3 percent during periods of low growth. By property sector, apartments and office performed better than retail and industrial during inflationary periods.

To some extent the results illustrate the inflation hedge maxim about commercial real estate. A good portion of the return comes from income returns, which represent growth in rent and are consistent over time in the stable properties that dominate the NPI index. Appreciation returns are somewhat more complicated, as they are based on the 10-year Treasury rate plus a risk premium that represents investors’ confidence levels.

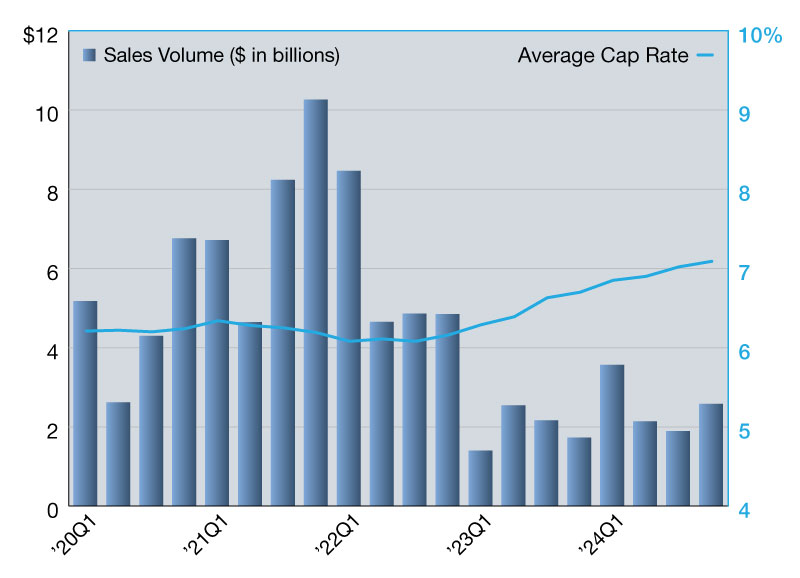

The strength of commercial real estate returns during periods of high inflation might best be explained by the fact that investors will pay higher prices (or lower acquisition yields/capitalization rates relative to Treasury rates) when they feel confident about future rents increasing. As the PREA study put it: “The effect of inflation on property is complicated, depending on how (net operating income) reacts and on how that NOI is valued by the market (i.e., cap rates).”

Still Much to Be Learned

There remains much to be learned about the impact of inflation on the economy and commercial real estate. One reason is that there are so many variables to performance. Another is that periods of high inflation have been relatively rare. The last such period was long ago when the economy and macroeconomic policy were different, so some of the lessons from that period may be less relevant today.

The evidence seems to indicate that high inflation over time is a lesser problem for commercial real estate than low growth. Even so, it is appropriate that policymakers adjust policy sooner rather than later to prevent negative impact to consumer and business confidence. And the real estate industry should not be sanguine about the potential for havoc that inflation could create and plan accordingly.

You must be logged in to post a comment.