Charting CRE’s New Capital Markets Landscape: Q&A

Chatham Financial Managing Director Robert Mangrelli on how the capital markets are reacting to higher interest rates.

Impacts of the Federal Reserve repeated interest rate hikes are reverberating across the real estate capital markets. To make some sense of the new landscape, Commercial Property Executive reached out to Rob Mangrelli, managing director of Chatham Financial hedging and capital markets team. He has been with the company for more than 15 years and is currently leading a team advising private equity real estate clients on interest rate and foreign currency risk management strategies.

The Federal Reserve increased its benchmark interest rate by another 75 basis points in June. How is this affecting commercial real estate?

Mangrelli: Given that commercial real estate is an asset class that is inherently capital intensive, it is dependent on credit to help finance the acquisition or construction of commercial real estate assets. Higher yields on risk-free instruments, including the policy rates set by the Federal Reserve, act as a reservation rate for all providers of capital, both debt and equity investors alike, and influence financial conditions. The increases in policy rates augment the cost of debt and equity capital for real estate, and such a rapid repricing in yields will cause a period of readjustment in lending markets. In addition to the impact of the Federal Reserve’s rapid increases in their policy rates and the rapid repricing of the Treasury yield curve over the course of 2022, the impact of higher rates and the general uncertainty over several macroeconomic factors, chiefly inflation, is leading to higher risk premia, including widening of credit spreads.

With recession fears on the mind of many market pundits, lenders will have to remain attuned to the impact of higher interest rates and tightening financial conditions on their existing loan portfolios. Specifically, to the extent rising interest rates lead to lower real estate valuations, reduced cash flow available to service debt, and/or higher vacancies due to higher unemployment or slower economic growth, there is likely to be a reassessment of exposure to commercial real estate from debt providers.

CRE loans are issued by banks, insurers, and non-banks (debt funds) and may be supported by GSEs. Many of these institutions also have exposure to commercial real estate through investments in CMBS and CRE CLOs. These loans may often be syndicated or securitized and there are linkages in this lending ecosystem that can ultimately impact the availability and price of credit.

In the face of heightened uncertainty and increased risk, investors in CMBS and CRE CLOs may require higher returns relative to returns lenders may have foreseen at the time they were underwriting their loans. This could make it more difficult for certain lenders to access the debt capital markets from which they intended to find more permanent financing for their loans and may further constrain bank and other balance sheet’s abilities to fund loans going forward.

It feels hard to believe that we are only a little more than two years removed from the heart of the COVID-19 pandemic that required the use of certain Federal Reserve-supported special lending facilities, like Term Asset‐Backed Securities Loan Facility, to help support lending and specifically supporting CMBS which is part of the nonbank credit intermediation chain. The COVID pandemic is a reminder of how quickly conditions can change.

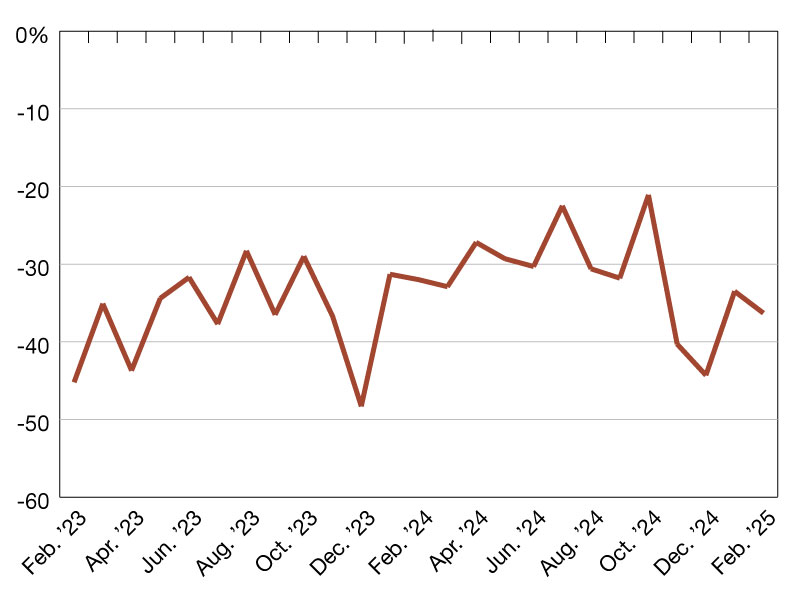

How much have prices and transaction volume been affected by higher rates?

Mangrelli: External data shows transaction volumes are slowing from what was a torrid pace, with price increases moderating. Rising interest rates and tighter financial conditions, coupled with heightened uncertainty over the path for economic growth and inflation, almost certainly had an impact here.

Floating-rate loans are a larger share of the market today than they were a few years ago. But now the cost of buying interest rate caps has skyrocketed. How much has the cost of interest rate caps increased?

Mangrelli: Depending on the economic structure of the interest rate cap, cap pricing has increased by anywhere from double to nearly 10 times the cost for a similar strike and tenor cap from six months ago. Cap purchasers have been confronted with a double whammy of higher rates and a steeper yield curve, increasing the intrinsic value of many caps, as well as heightened volatilities, increasing the time value of many caps.

Are there ways to structure deals to ease the burden of the increase in rate cap costs?

Mangrelli: There are a number of approaches to reduce the financial burden of higher up-front premiums on interest rate caps. The most common approaches include shortening the tenor of the cap and increasing the strike rate of the cap. Any approaches employed by both borrowers and lenders to defray higher cost of caps inherently involve a tradeoff with increased risk exposure to rates exceeding then-current market pricing.

For example, if the tenor of the cap is decreased from three years to two years, there is a risk that the cost of any required hedge two years from today could exceed the cost of that third year today. Similarly, increasing the cap strike can constrain debt service coverage, especially if part of the premise of the lender accepting the higher strike was an expected increase in NOI that fails to come to fruition.

Has the increase in the cost of interest rate caps affected borrower demand for mortgages and does that favor one type of lender over others?

Mangrelli: There are numerous factors that drive borrower demand for mortgages and, specifically, borrower preference for floating- or fixed-rate debt capital. These factors include the amount of risk the borrower may be willing to accept, the cost, including the carry, prepayment flexibility, covenants, and the borrower’s plan of the asset.

Flexibility on interest rate cap requirements may not be a sole determinant for a borrower selecting a lender. Still, the cost of caps is certainly something borrowers need to consider when underwriting their real estate deals. We are seeing more lenders—especially non-bank lenders and those who intend to keep loans on their balance sheet—offering increased flexibility around interest rate caps for certain loans. In some respects, market participants, such as banks, who can offer their borrowers synthetic fixed-rate loans (swapped floaters) or otherwise offer their borrowers more flexibility in derivatives, including deferred premium caps, may find relative favor with some subset of borrowers.

How smoothly has the market transitioned to pricing based off the Secured Overnight Financing Rate as opposed to LIBOR?

Mangrelli: U.S. supervisory guidance declared “no new LIBOR” to start 2022. In general, I would characterize the transition as relatively smooth, though some challenges remain, such as ongoing education around SOFR variations, differences in how lenders have approached the use of CAS (credit adjustment spreads), and the ongoing conversion of legacy LIBOR loans.

In commercial real estate, we see one-month CME Term SOFR leading the market as a SOFR index for loans, but various alternatives such as NY Fed 30-day Average SOFR, Daily Simple SOFR, and Compounded SOFR, are all also commonly used. While all these indexes are based on SOFR, the floating rate lending markets for CRE have been historically accustomed to a single index, 1M USD-LIBOR-BBA. Borrowers and lenders have had to get familiar with varying loan mechanics in these different SOFR alternatives to ensure their systems can support them. It is not much of a surprise that one-month CME Term SOFR has taken a leading market share in the cash market as the index is most similar to LIBOR.

In the early months of 2022, many lenders were quoting loans with a credit adjustment spread, which was an additional number of basis points that was added as a fixed component to the variable SOFR index. The purpose of the CAS was to reflect the difference between LIBOR and SOFR indexes, meaning lenders didn’t need to incorporate that difference in their loan margins. As the year has progressed, increasingly, the use of these CAS has fallen away from new loans with borrowers and lenders negotiating the loan margin over the SOFR index.

Markets are also continuing to adjust to the fact that CME Term SOFR is only to be used in the derivatives market if it is linked to an end-user hedging exposure from a cash market (loan) referencing that index. While this means that end-user borrowers can hedge with CME Term SOFR derivatives, dealers are prohibited from trading CME Term SOFR in the inter-dealer market. The lack of dealer ability to hedge their risk and a lack of central clearing for CME Term SOFR has led to dealers charging customers a spread for derivatives tied to CME Term SOFR. This creates another variable CRE borrowers need to consider when comparing loan alternatives that they may seek to hedge.

The spike in interest rates and increase in bond spreads have increased the cost of hedging for lenders. What types of lenders are most affected by this?

Mangrelli: Lenders that lack the ability to quickly expand balance sheet capacity to retain loans (on their balance sheet) are the most likely to be impacted by the rising rates and spreads. These institutions—typically non-bank lenders—make use of the securitization markets to raise funding for their loans. With rising interest rates and a deteriorating macroeconomic environment, investors in CMBS are requiring higher yields, which directly impacts the cost of funds for certain lenders.

This is not to say bank balance sheets aren’t immune from uncertainty impacting the CMBS funding markets, as banks often take on large loan assignments either on a principal or agented basis. For dealers where dealers are principal, the increased capital markets uncertainty will likely lead them to widen pricing to borrowers or propose “flex pricing.”

Lenders use a mix of interest rate and credit hedging products to manage their exposures on loans they originate intended for securitization, so the exact impact can be hard to tell, other than to say that the longer loans stay on the balance sheet, the lower the velocity of loans is likely to be. Higher costs and the possibility of spreads/margins being repriced prior to closing impact borrowers. They are also impacted in that to the extent there is less balance sheet capacity in the lending system.

What types of investments have become riskier in the current economic environment?

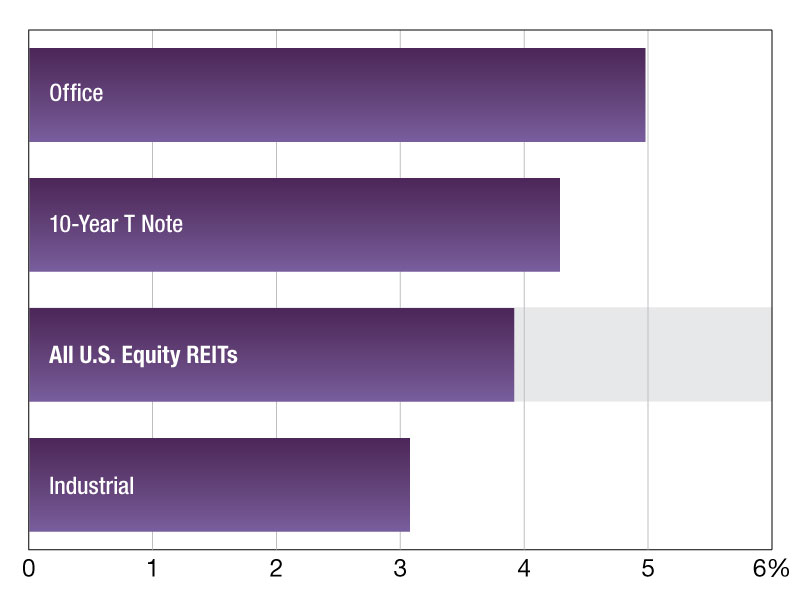

Mangrelli: Investments exposed to higher interest rates have become riskier in the current environment. In commercial real estate, some property types tend to look more like fixed-rate bond assets due to their lease profiles, which make them more sensitive to interest rates. Other investments may be riskier due to their dependence on the availability of cheap debt financing to maintain their originally underwritten levered return objectives.

What advice do you give investors about making safe investments in an uncertain environment?

Mangrelli: As always, investors in all asset classes should understand the various components of their return, including the real risk-free rate, inflation expectations and risk premiums, along with the risks inherent in their investments. Understanding these components of investment return, and how they are impacted by macroeconomic variables—such as the current interest rate environment—coupled with understanding your risk tolerance and having a good risk management framework, is advice that is rarely going to be out of style.

You must be logged in to post a comment.