What Does It Take to Complete the Transition to Renewable Energy?

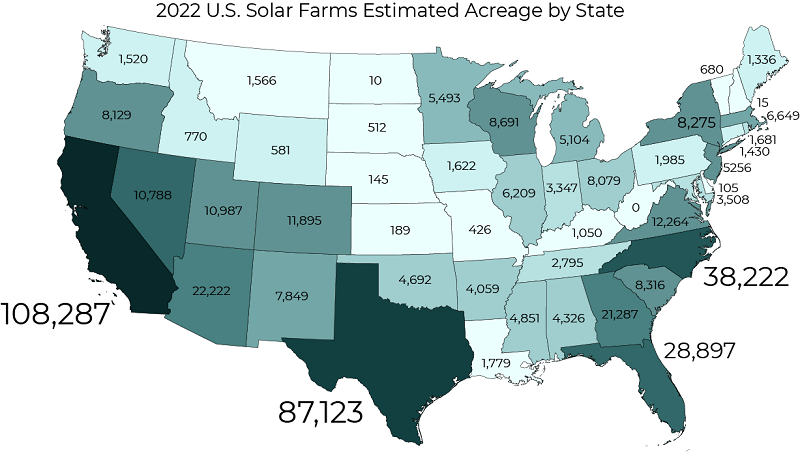

LandGate Founder & CEO Yoann Hispa says some 26 million acres of land—roughly the size of Kentucky—is dedicated to renewable energy.

The energy industry has been greening steadily over the past decade, sustained by the evolution of technology and increased awareness, as well as new legislation. Yet, despite the accelerated spending on green technologies, the International Energy Agency reports that the world is still not on track to reach zero-net emissions by 2050.

At a closer look, only about half of the spending increase is due to investments in new clean energy capacity, while the other half is due to rising prices—driven mainly by severe restraints of supply chains. Many of the rare earth minerals and other materials necessary to produce transmission lines and solar cells are sourced from China, and with the tariffs imposed on Chinese goods, the overall price of these components has increased, hindering production and installation.

But there are other threats to the growth of the renewable energy industry including the war in Ukraine—which left Europe struggling to find a way to replace the Russian liquefied natural gas and eyeing a return to coal—the growth of coal in China and India and the inadequate infrastructure, which, as it currently is, cannot handle the increasing load coming from renewable sources.

READ ALSO: All-Electric Real Estate: The Movement Gains Momentum

Commercial Property Executive talked about the evolution of the U.S. energy market with Yoann Hispa, founder & CEO of LandGate, a marketplace and data provider for commercial land and its resources.

What happened to solar and wind development across the U.S. during the last couple of years?

Hispa: During the two pandemic years, solar and wind development across the U.S. increased dramatically despite drastic political change and supply-chain issues.

In the pre-pandemic years of 2017 to 2019, the U.S. appetite for renewable energy faltered. The administration publicized plans to establish U.S. energy independence by increasing the export of natural gas, coal and petroleum. Naturally, investors became somewhat uncertain about the future of wind and solar energy, and there was a slump in development and investments.

However, in 2020, wind and solar farm development began to grow exponentially. In terms of the pandemic impact, on the one hand, renewable energy grew tremendously during the past two years, but on the other, the supply-chain issues originating from the pandemic hindered its growth. If not for those issues, the renewable development boom would have been even more dramatic.

How are the current economic woes—rising inflation, rising gas price, rising interest rates—affecting the progression of the renewable energy industry?

Hispa: The current state of the economy has impacted the renewable energy industry in more than one way. From one perspective, rising gas and oil prices should be beneficial, as they make renewable energy sources more competitive in the energy markets from a price basis. However, one of the major factors of this economic/geopolitical mess in the aftermath of the pandemic is supply-chain issues, as solar developers, for example, are having trouble getting the materials needed to manufacture solar cells.

With rising interest rates, the economics of some solar projects change, as well. In particular, we can expect solar royalties to start declining. But overall, I wouldn’t expect the capital flowing into the renewables market to decrease significantly.

Which states are leading in renewable energy production? Which states appear to be the industry’s late bloomers?

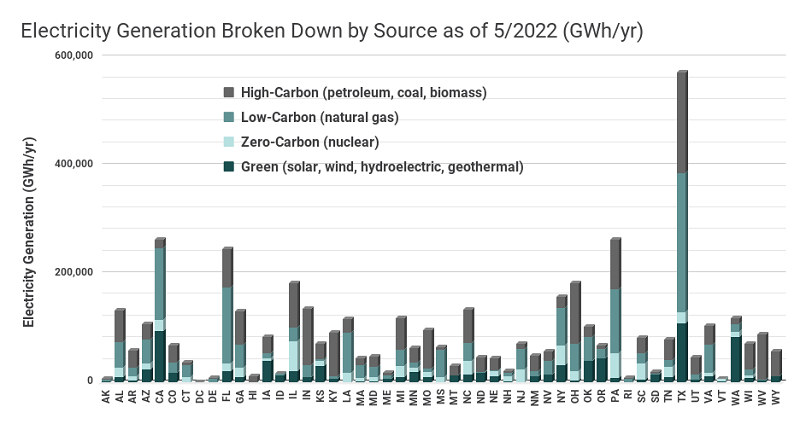

Hispa: The states currently leading in renewable energy production—including solar, geothermal, hydroelectric and wind—are Texas, California, Washington and Oregon.

Excluding some of the smaller states (such as Delaware, Rhode Island and Connecticut), which lag for obvious reasons, the states with the lowest renewable energy production are Missouri, Louisiana and Arkansas.

In addition to the favorable geographical factor, what is driving solar and wind development in these states? Policies, climate change awareness, necessity?

Hispa: Generally, the main factors driving solar and wind development are state/local policy incentives. For example, Massachusetts—which is not a very large or sunny state—is among the leaders in solar development because of very robust state incentives.

However, for the leading renewable energy state, Texas, this is not the case. Despite the lack of policy incentives, Texas leads the country in both wind and solar generation. Texas’ market-leading position is, at least in part, attributable to its long-held status as the capital of energy in the U.S. As the energy market shifts, many former oil and gas professionals in Texas are reinventing themselves in solar and wind, and the robust energy labor force and infrastructure are playing a role in the growth of the state’s renewable market.

For the top three states in the non-Texas category, state and local incentives have been very significant in driving solar and wind energy development. California is a prime example of this and has been a longtime leader in renewable energy production. However, California’s infrastructure challenges, such as a lack of transmission lines and substations, have left the state saturated and unable to reach its potential in terms of renewable energy production.

Another crucial factor for solar and wind development is the resource itself. To produce solar or wind energy, you need a certain amount of access to sunlight and wind to create power. I mentioned Massachusetts as a counter-example—a state with middling sunlight, which has a lot of solar—but you wouldn’t place a wind farm in states like Arizona and California, with low average wind speeds. Instead, wind farms typically occupy the Great Plains and states like Nebraska, Kansas and Iowa.

How can a landowner determine whether their land is suitable for solar or wind farms and what steps should they take to submit their land to renewable energy generation?

Hispa: First of all, it is important to consider the buildable acreage. Additionally, proximity to substations and transmission lines with hosting capacity is a key determinant.

Land, in and of itself, is not sufficient. The type of land and the surrounding environment are factors in determining the ability to produce solar or wind energy. For example, wetlands—which take up a sizable portion of coastal states like Delaware, Florida and Louisiana—are not practical for solar/wind farm development, nor are waterways, flood zones or national parks.

While buildable land is essential, the notion that you need a huge amount of direct sunlight for solar is a misconception. New England is one of the least sunny regions in the U.S. but has many solar farms.

In terms of wind development, the most obvious necessity is that the land needs to have the requisite wind speeds to move wind turbines, which are surprisingly large to anyone who hasn’t seen them. Like solar farms, wind farms also must be near substations and transmission lines with available capacity.

How much land would you say is currently available in the U.S. for energy leasing? How is the market trending?

Hispa: I don’t think it’s as relevant to discuss the hard figure of land available for leasing, because many people aren’t even aware that they can lease their land for solar or how they would go about signing a solar royalty agreement. Even for those who are aware, many landowners fear the energy companies and expect to be swindled. As a result, a lot of suitable lands are not “available” for energy leasing—even though they logically should be.

Despite all these obstacles to the renewables market, the market for solar farming is increasing exponentially, and we are seeing a massive land grab for the development of solar farms.

Tell us more about your theory on achieving carbon neutrality—how long, at what pace and what capacity is needed to reach a fully renewable grid?

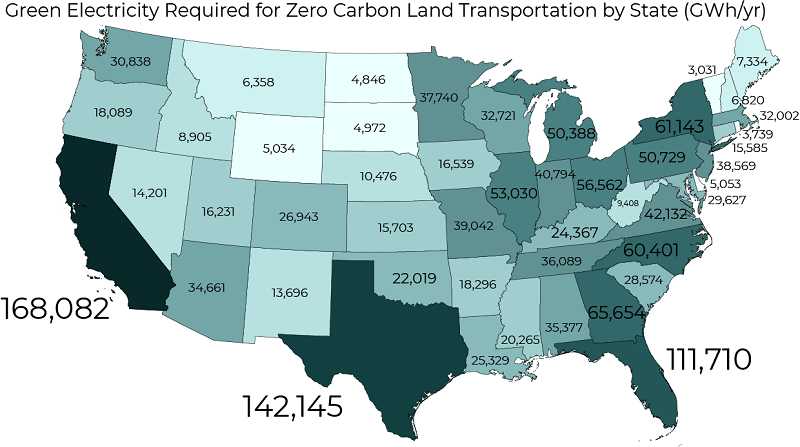

Hispa: While in the past 12 years, the U.S. has doubled the amount of electric energy consumption that is generated by renewable energy, fossil fuels still power more than 80 percent of the country. Considering a variety of factors, we have determined that another 26 million acres of land—roughly the size of Kentucky—dedicated to renewable energy generation is required to reach carbon neutrality. While this is a tremendous amount of real estate, it is only 1 percent of the country’s acreage and is clearly a worthwhile investment to make the U.S. carbon neutral.

For more than a decade, the growth of renewables has been slow and steady. With technological advances, declining costs for solar and wind power generation compared to fossil fuels, and capital increasingly being allocated toward climate-friendly investment, the pace of expansion is likely to improve.

In terms of the timeline, it’s hard to say when we’ll get there, but it’s clear that we’re making progress. Several obstacles must be overcome, including—critically—the lack of infrastructure to support renewable energy transmission in many locations. I can’t honestly say I expect to see a fully renewable grid in the next 10 years, but I do hope we’ll be much on the way there by that point.

What do you foresee will happen by the end of the year? Are we looking at a (brief) pause in renewable power expansion?

Hispa: I am optimistic about the future of renewable energy. Renewable power generation has been growing rapidly, and that trend should continue through the year and beyond. Ultimately, we’re talking about a generational opportunity to reimagine the way we use power, which is already having benefits for landowners, investors and the planet. A few obstacles notwithstanding, I do believe that this is the wave of the future—a wave that will not turn back.

You must be logged in to post a comment.