Strong Growth in a Unique Cycle

Pent-up demand has fueled a boost in U.S. GDP, according to economist Peter Linneman.

We are continually amazed that observers are surprised by the strength of the U.S. economy. They look at the strong job growth and real GDP increases as if these indicators are part of a normal economic cycle. But they are decidedly not. We are still making up for the extraordinary losses experienced during the pandemic. Employment and real GDP remain well below pre-pandemic trends, workers over 60 have yet to fully return to employment (much less continue their 30-year trend of ever-rising labor force participation) and government spending remains at wartime levels.

Pockets of pent-up demand remain in the economy, though much less than over the past four years. There remain forestalled vacations, new and used cars to be purchased, aching hips to be replaced, and (unfortunately) overlooked cancers to be treated. This pent-up economic demand is worth an additional 40-50 bps of annual real GDP growth even if it is spread over the next four years. This is on top of normal economic growth.

You may recall that we were the first to point out that about 42 percent of all households had opportunistically locked in ultra-low mortgage rates. These households now have additional spending power versus normal economic conditions. These locked-in mortgage rates have buffered many households from rate increases, while making them less likely to move.

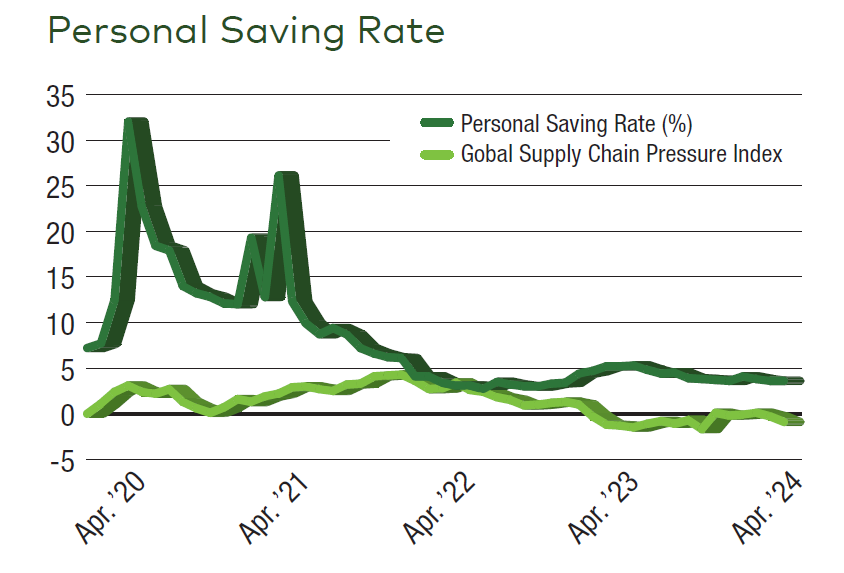

Further boosting the economy is that the vast Fed injections during the pandemic were largely saved. This behavior is in line with Milton Friedman’s permanent income hypothesis. He argued that a sudden large one time jump in income would generally be saved rather than immediately spent, becoming part of household wealth. Understand that when we increased the national debt during the pandemic, all we did was borrow against our future incomes. As this was done in the face of enormous uncertainty, it is not surprising that we did not see a corresponding surge in spending. Instead, we saw a surge of savings (from 7.7 percent to 32 percent), primarily in the form of cash.

Post-pandemic inflation was primarily due to the normalization of spending patterns (though not fully) occurring faster than the normalization of supply chains. Unprecedented supply shortages appeared globally, not because demand was so high, but rather because supply was so low. This is vividly seen in the explosion of the Federal Reserve supply chain index. As we argued at the time, this was always going to be transitory inflation, which would disappear as supply caught up with demand. It would have disappeared at basically the same speed if the Fed had increased rates to about 3 percent. It was like a cold that is gone in two to three long and miserable weeks whether you take an antibiotic or not. As the Fed’s supply chain index normalized, so too did inflation. Once the Fed raised rates from zero to 2.5 to 3 percent, they had no more to do with inflation normalization than did the rain that came after a high priest’s animal sacrifice. Remember that the way that rate increases are supposed to stop inflation is by bringing economic growth to a halt. But growth continued even as the Fed raised rates because pent-up demand was released. If these high rates did not halt growth, they could not have halted inflation.

Add to this the fact that government, education, health care, staples and much of the rest of the economy are largely immune to interest rate increases. Babies will be delivered, children will go to school, totaled cars and destroyed homes will be replaced and police officers will be hired to fill depleted ranks irrespective of short-term rates.

A further boost to the economy has come from the Ukraine war. We wrote in the issue after the war began over two years ago that it would benefit the U.S. economy. This is because U.S. companies are major global suppliers of oil and gas, defense systems and agricultural products. We said at the time that increased demand and for these items in light of the war would boost U.S. real GDP by 40 to 80 bps annually. This appears to be the case.

In short, this is not a typical cycle. We have seen pandemic-created supply shortfalls and pent-up demand working their way through the system after a unique economic and societal event. The U.S. is imperfect in innumerable ways, but it remains the home of innovation, hard work, meritocracy and freedom, all of which drive the economy. We urge you not to miss this growing “forest” among the problem “trees.” Every amazing forest has weak and dead trees, but that does not cancel the forest’s majesty and ability to flourish.

Dr. Peter Linneman is a Principal and Founder of Linneman Associates (www.linnemanassociates.com), Professor Emeritus at the Wharton School of Business, University of Pennsylvania, author of “Real Estate Finance and Investments: Risks and Opportunities,” and co-author of “The Great Age Reboot: Cracking the Longevity Code for a Longer Tomorrow.” Follow Dr. Linneman on X: @P_Linneman

You must be logged in to post a comment.