Designing Buildings With Conversion in Mind

Flexible architecture ensures long-term value and sustainability.

Converting buildings is not new by any stretch. Essentially, it lets investors respond to changing conditions and needs, also adapting to new uses as they’re identified. And while today’s conversation is frequently about office-to-residential, every CRE sector has its share of success stories.

Increasingly, the focus has expanded to include new construction. Architects are leading this discussion on how to future-proof new construction—by baking in flexibility at the beginning of the life cycle—and developers are listening.

Flexible architecture that takes into consideration future adaptive reuse potential will cost more upfront, but future iterations across sectors will be easier and less expensive.

Planning in flexibility

“Historically, we’ve seen many types of buildings repurposed—banks turning into restaurants, old theaters into malls and post offices becoming performing arts centers,” said Zoltan Pali, co-founder & design principal at SPF:a. “What we’re seeing now, however, is a more proactive approach to designing new buildings with an eye on flexibility from the start.“

READ ALSO: Can Adaptive Reuse Revitalize US Cities?

Developers are attempting to anticipate future changes, creating spaces that allow for smoother, easier transitions. “The current trend leans more toward enabling easy reconfigurations rather than massive overhauls like transforming a multi-level department store into a museum, which is often a complex, resource-heavy process,” Pali added.

A good example of future-proofing is the Bezdek Center for the Performing Arts at the Crossroads School for Arts & Sciences in Santa Monica, Calif. There, each space was designed with potential new uses in mind. Even areas such as storage rooms, green rooms or loading docks were thought to maybe one day become classrooms. Infrastructure was also laid out to facilitate potential shifts over time.

Making design choices

“When I think about flexible design, the word that comes to me is ‘resilience,’” said Jooyeol Oh, principal with MG2.

This goes beyond function. “We should think about and talk about the other half of design, which is aesthetics and the emotional component. How do users experience a building when they pass by or interact with it?” People will want to preserve some buildings, while others won’t be missed if replaced.

“Flexible design is a challenge, but it’s a challenge that we always think about,” said Oh. He recalled that 20 years ago, during graduate school, he was tasked with envisioning a flexible office building of the future. He realized that creating more perimeter space for workstations and designing a shallower floorplate would facilitate an easier conversion to residential. Another takeaway was the disadvantage of a hermetically sealed facade when future-proofing.

READ ALSO: Why Conversion Isn’t CRE’s Magic Bullet

As a practitioner, he’s had a chance to bring these ideas into his work. “One of my projects was an office building essentially, but they were thinking of potentially converting some floors into residential in the future,” recalled Oh.

“That made us think about what we could do to make it flexible in case they actually wanted to expand those buildings and the number of floors.” This included how to lay out columns as well as vertical transportation because elevators would need to be grouped together. Access to daylight and fresh air were also top considerations.

According to Oh, “If we think of those things when we design, then it’ll be easier to convert later. If you put too many columns, then it’s not too conducive to retail. The best practice typically is to make it as wide of a spacing as possible.” A bigger spacing of columns helps ensure a future flexibility is baked into the design.

Creating easier transitions

It’s never too early in the design process to begin thinking about flexibility. “Look at the shell and infrastructure from multiple different angles so that what does get constructed could be most easily converted to different things,” said Eric Hudson, principal with Method Architecture. “Consider what’s permanent and how that would affect layouts for different types of uses.”

Hudson’s team explores which decisions made now will allow for flexibility in 10 to 30 years. If something else needs to be in this location, what else could it be? Investors are keen to make decisions now that will help them or the next owner transition, if needed, in the future.

“I think the concept of being able to build something within something else is really powerful. It can save money if the original infrastructure is set up enough for it,” Hudson noted.

He suggested grouping utilities in a location that’ll probably never need to move. Also, orienting the site with accessibility from multiple different points—something an industrial site doesn’t need now, but a retail or residential environment will in the future.

“Start looking at those major elements and say, ‘This is what we need for our current development. Let’s throw out different ideas to make ourselves the most flexible possible, so that we can pivot more easily later.’ We don’t have a crystal ball. Some predictions may not pan out.”

Designing perpetual assets

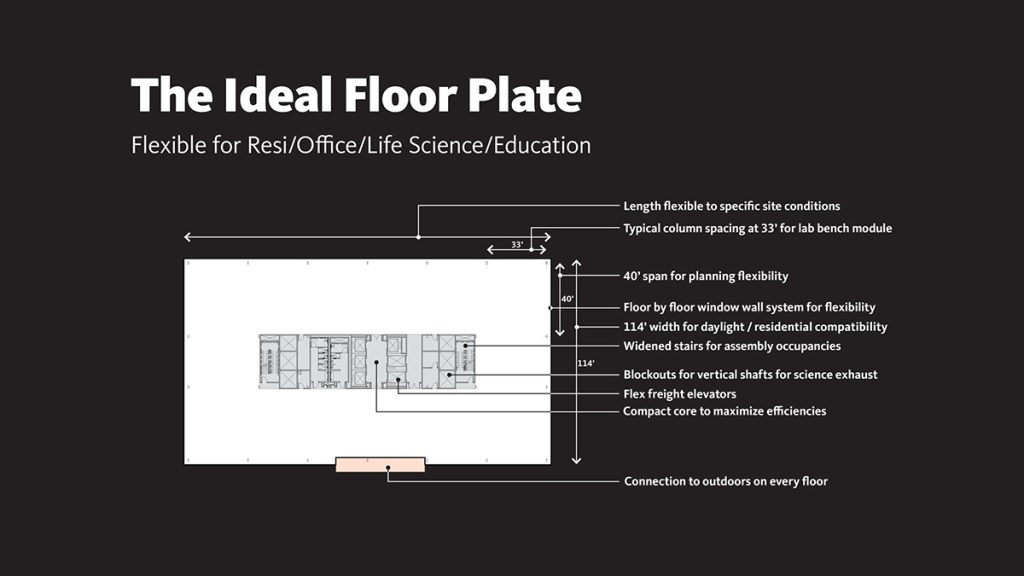

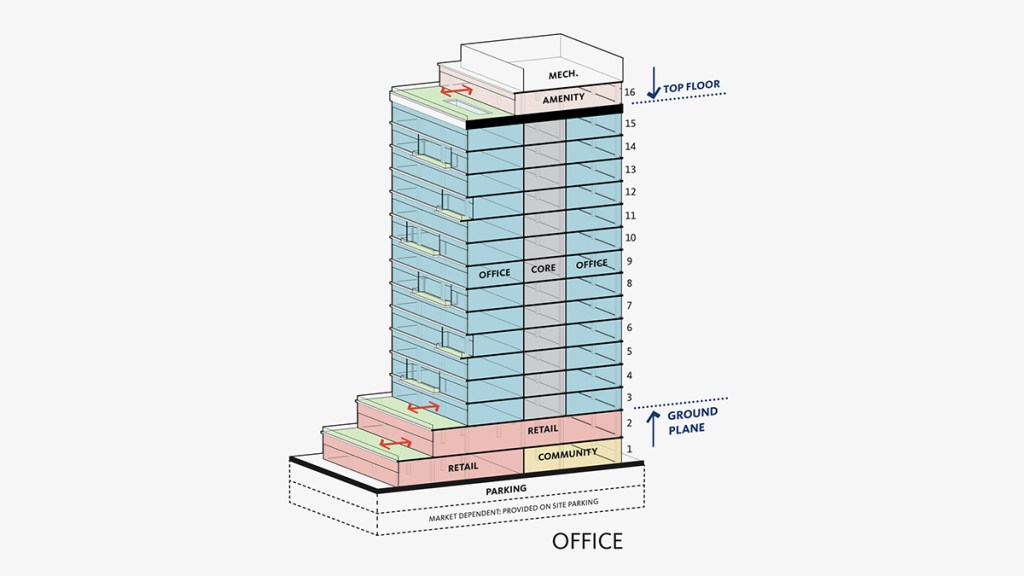

Gensler has assessed hundreds of potential building conversions and identified four key areas to address early in the design process to maximize adaptability:

- the ideal floorplate

- connectivity at the ground plane

- amenities on the top floor

- facade considerations

“One of the key things we avoid is curtainwall, because it gives you no flexibility down the road to pop in balconies where you might want them for whatever reasons, or to upgrade some parts of the building without having to upgrade the entire facade,” said Darrel Fullbright, a principal at Gensler.

As part of flexible design, Fullbright has been pushing for a floor-by-floor window system that builds in more flexibility for a variety of future changes, from residential to life science.

READ ALSO: Why the Office-to-Lab Conversion Trend Will Last

“Almost every office building that I’ve been designing recently has the flexibility to go to life science,” mentioned Fullbright. This is possible because of higher floor-to-ceiling heights. Life science requires higher ceilings to run mechanical systems and more space to fit all the ducts for science use. There are different types of equipment for science space that you don’t have in office space. “We’re also hardening floors a bit. You can’t have vibration when there is scientific equipment.”

A huge plus for flexibility is to get as much power to the building as possible, because needs can continue to increase either from lab use, office or sometimes data centers going into offices.

A recent McKinsey study predicts data center demand in the U.S. will grow by 10 percent annually until 2030, more than doubling power consumption during that time to an estimated 35 gigawatts annually.

“Data centers can no longer be in the next state because the computing power needs to be more immediate, so you’re going to see a lot of micro data centers located in all kinds of different places,” said Fullbright.

READ ALSO: Meeting the Insatiable Demand for Data Centers

The ground floors must be flexible too, which means that they need to either be retail, community or event spaces. The top floor should be designed with residential- or hotel-style amenities—even for the office and science people—that can provide a leg up on the competition.

“We design the roofs so that they step back. That top floor can be an amenity with an outdoor deck and maybe even a pool. The actual roof we reserve for mechanical equipment,” added Fullbright.

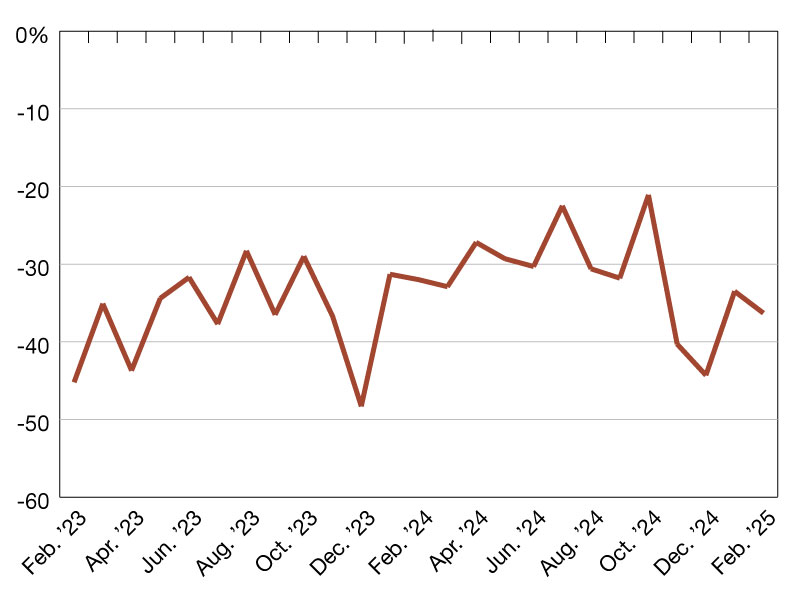

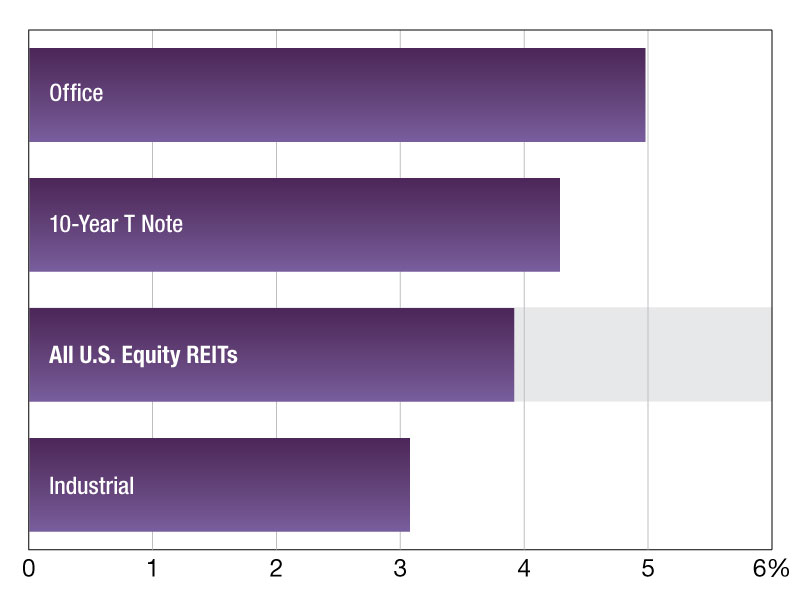

Interest is growing

Another benefit of easily convertible buildings is that they conserve carbon. Fullbright pointed out that buildings are incredibly carbon intensive, not just to operate but also to build. If you can extend the lifespan of a building by 20 or 30 or 40 years versus tearing it down, that will create an incredible amount of carbon savings.

LEED certification statistics for the office sector show how the program has gained widespread acceptance after a slow start. The initial response to flexible architecture from developers is similar to when LEED first came out. They question the value of flexible design. Obviously, it’s going to cost more to do it. The question is, does it increase the long-term value of the building?

According to Fullbright, developers have started realizing even if they don’t get more rent for it, they will get more money for the building long term. “That’s how we see this idea of the perpetual asset,” he added. “Yes, it will take a little bit more money to build up front, but long term—once the market gets wise to this—they’ll say, ‘If you design a building that is a more of a perpetual asset, it should have a longer-term value because it’s going to be easier to adapt to changing market conditions.’”

You must be logged in to post a comment.