A Smart Approach to Turning Old Into New

Panelists at Expo Real 2021 discuss how building renovations can benefit investors, users and the environment.

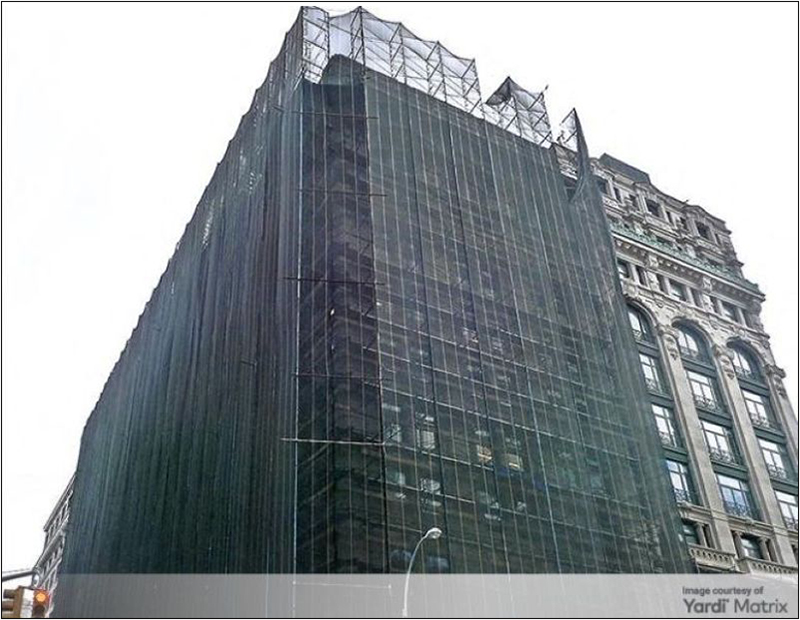

The renovation and refurbishment of old buildings is becoming increasingly important as workers and resources are become scarce, particularly in urban settings. Moreover, the pressure of climate change is mounting, so what can be done?

During the second day of the Expo Real conference in Munich, Catella Managing Director Thomas Beyerle joined Felix Dorner, CFO of aedifion; Franz Peteranderl, president of the Chamber of Crafts for Munich and Upper Bavaria; Konrad Jerusalem, managing director of Argentus; and Steffen Szeidl, CEO of construction engineering company Drees & Sommer, in a panel on climate protection and how it relates to existing buildings.

READ ALSO: Expo Real 2021: Has the Pandemic Changed Everything?

Drees & Sommer has collaborated with more than 4,200 architects, engineers, biologists and chemists on asset improvement and planning accompanying a building across its entire life cycle, focusing on digitalization and sustainability. Argentus, which looks into sustainability for real estate portfolios, counts on data compilation to help its clients—which is not always easy.

The importance of data is something BNP Paribas CEO Claus Thomas also outlined in a separate discussion the day before. “You can only manage what you can measure. Data is required so you can actually prove that you meet the ESG criteria for a specific property,” he said.

While data monitorization and collection techniques are achievable for newer buildings, what’s there to be done with the remaining 99 percent of existing buildings? Peteranderl, who represents 207,000 craftsmen with 960,000 employees in Bavaria, Germany—with the bulk working in construction and interior design, including rehabilitation and thermal insulation of buildings—is not seeing a major lever because there is no standard to benchmark against.

Different approaches, same aim

Sustainability starts with tax-related or regulatory requirements. Germany leads the way in this sense, with more than 20,000 regulations set in place, Szeidl said.

What needs to be done is to find alternatives and it is up to engineers to find new options. This will pave the way for a greater readiness to innovate and more money to be spent on these new aspects, he added.

With existing buildings, something old gets turned into something new, but what does new mean? Smart—obviously. But will thousands of sensors integrated in an old building make it more sustainable or useful?

The panelists believe this depends on who the user is and how the building is being used. Then, but only then, should the right solution be created. While technology may be an option, it might not always be the right one because some buildings simply work in a much more sensible fashion.

We have to take into account the climatic region the building is in, which is reflected through its color, size and shape. “These are criteria we have abandoned but which continue to rank high on the agenda of other regions,” Szeidl said. “Let’s take East Asia, for example, where they may tear everything down in 20 years, so demolition and deconstruction weighs equally as much as refurbishment,” he continued.

Regulating the human factor

Peteranderl brought up an issue often faced by Bavarian craftsmen, considering the decisive aspect in construction is the type of materials used. Should regulations be more specific or is it up to craftsmen to think about the material in terms of what makes sense for the future and what is sustainable?

What is required as a holistic approach to rehabilitate a building and make it more sustainable might come in contradiction with what’s worth for the building owner down the road.

“That’s why so many people fail to understand how things tie in. There’s hardly any architect or engineer that would be aware of the entire standard procedure,” Peteranderl said.

Some 90 percent of Germany’s buildings have functioned so far thanks to lean standards combined with people’s ability to keep track and understand how things fit together. Today, there are industries that are black boxes, such as automobile production. While the process is as exact as it can be and highly automatized, this reflects differently on the real estate industry, where it’s harder to measure what energy flows apply, where energy can be saved or where there is risk involved.

“I think we have to start at the beginning. We have to turn these black boxes into crystal balls…and to understand the project in order to achieve the smart degree mentioned before,” Jerusalem continued.

READ ALSO: Expo Real 2021: Will COVID-19 Have a Lasting Impact?

While innovation is pivotal, Dorner believes we have to learn how to work with the technologies installed into a building. First, we have to settle the status quo to know what kind of technology we have. Let’s take for example the buildings constructed in the 1960s. Some people don’t know their systems were refurbished and linked to newer ones. Maybe not optimally, but an examiner should check this out and then start with optimization.

“We have to learn to live with what we have, as it is way more expensive to change the building system overnight,” Dorner said.

But even if you end up with a refurbished asset, there are limiting factors which can lead to stranded assets five years down the road. These include the availability of construction materials and the human factor. While digitalization might be the solution, everything starts with proper education and training. A different mindset is also needed, alongside a focus on pre-manufacturing and pre-fabrication, while taking into account craftsmanship.

According to Peteranderl, the real estate industry needs skilled people and workers, but nowadays there are a third less certifications issued in training and education than there were 10 years ago. In the next 10 years, all Baby Boomers will retire and fewer people will take over. Refurbishing older buildings will prove more difficult with fewer construction workers. To show how serious the situation is, Peteranderl said Germany had some 1.4 million construction workers in the 90s, but there are only 900,000 today.

The human factor plays a far more important role in a building’s life cycle than we would think, Jerusalem noted. People—such as facility managers or tenants—might know more about the assets in question. In one of its optimization efforts, his company surveyed tenants in a building and asked them to come up with five ways to save energy. The response was overwhelming, with tenants having a major impact onto the energy consumption within the facility.

You must be logged in to post a comment.