Building for the Future by Harnessing the Past

On day two at Greenbuild, three architects shared concepts for a sustainable future stemming from methods used thousands of years ago.

One of the main misconceptions about green building is that it’s not for everyone—because it’s too expensive and difficult to achieve—but just for the privileged. This misconception is not just wrong but, it is also extremely damaging as the most affected by climate change are, in fact, low-income people. And the irony behind all this is that the people who are most affected by climate change are those who did the least to cause it.

On the second day of the Greenbuild virtual conference, three keynote speakers, all architects, shared a set of perspectives that very easily debunked the concept that green building is available to just a select group of people. Kotchakorn Voraakhom, Julia Watson and Catherine Huang brought into the virtual spotlight systems and methods—some dating back thousands of years—to live collaboratively with the landscape.

READ ALSO: Sustainability at a Crossroads: Greenbuild Speakers Assess the Stakes

Julia Watson, architect, landscape designer and Harvard and Columbia professor, began her speech by reminiscing the wildfires in Australia earlier this year—the worst wildfires the country has ever seen. These are the result of seasonal drought and delayed rains caused by global warming, as well as underfunded prevention and century-old bans on traditional ecological technologies. Watson pointed out that the ancestral lands that still practiced pyro technology or cultural burning—a method used by the Kayapó in the Amazon Basin who use fire to clear away dead leaves and cultivate their crops, replenish the soil and protect their land from deforestation—were saved, while the wildfires destroyed everything around them. This indigenous technology, which evolved over millennia, cut back on the wildfires by more than half.

READ ALSO: How Will the California Wildfires Impact CRE?

Not long after the disaster in Australia, similar wildfires set alight vast areas in the U.S. And so, Watson raised the question: What if, just like this pyro technology, some of these wildfires are sustainable innovations rooted in cultures that figured out technologies a millennia ago?

If technology is the answer, what is the question?

This riddle that dates back to the 1960s leads today to another one—if sustainability is the answer, what is the question? And to what end will sustainability really save our planet? According to Watson, in order to mitigate climate change, we need to recognize that a solution that is embedded in the traditional knowledge of a community in its environment is the most effective way to approach resilience at scale.

Watson offered a few examples of systems originating from thousands of years ago in ancient cultures. She gathered these case studies in a book, LO-TEK Design by Radical Indigenism. The TEK stands for traditional ecological knowledge, while Radical Indigenism is a philosophy that was inspired by a professor from Princeton University who talked about the idea of rebuilding knowledge through explorations of indigenous philosophies that are capable of generating new knowledge for present times and new dialogue for the future.

Tribal communities, seen by many as primitive, are highly advanced when it comes to creating systems in symbiosis with the natural world, Watson said. Through these systems, biodiversity was increased, food was produced, floods were mitigated, waters were cleaned and carbon was sequestered.

READ ALSO: A Deep Dive Into Water Management Strategies

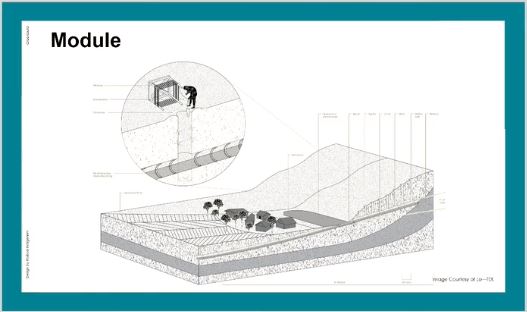

One such system was created by the Persians, a culture that lived in a very arid environment and for whom water conservation was vital. Yet, they didn’t suffer from the lack of water because they had invented a system that brought water from the mountains to the cities that lacked access to this resource. Water was brought in through underground aqueducts—qanats or underground tunnels dug manually—which serve as natural foils to our energy-intensive pumps and wells. These aqueducts also worked as an evaporative cooler that stored ice in the summer.

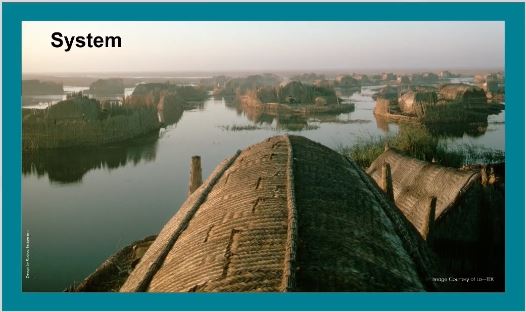

Watson also mentioned a type of housing and islanding system dating back more than 6,500 years ago in Iraq, made of reed in just three days. These villages and islands, which last for 25 years on average, still exist today and are made in the same way.

Another example is the wastewater treatment system in Kolkata, which cleans the sewage for a city of 15 million people through a combination of sunshine, sewage and a symbiosis between algae and bacteria. The system comprises 300 fishponds that clean the water continuously in a process that takes 30 days. In addition, these wetlands help produce vegetables for the city while saving millions of dollars a year compared to the operating costs of an actual sewage treatment plant.

In the light of these examples, reanalyzing the framework of industrialized, digital high-tech—which removes us from nature—and reframing the potential of the toolkit in our urban environments becomes more and more stringent, in Watson’s opinion. We need to see ourselves as part of the environment, not separate from it, and develop a symbiotic relationship with our surroundings. In a world with great access to education, news, resource sand ideas, “we are drowning in this age of information, but we are starving for wisdom,” Watson said.

How to live with water (again)

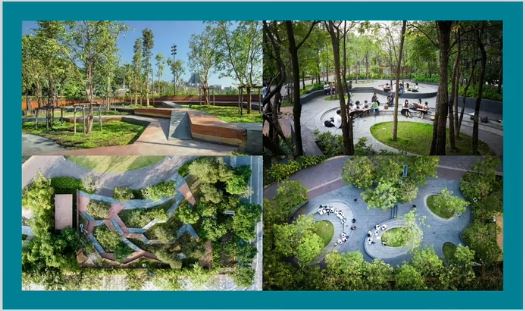

Kotchakorn Voraakhom, landscape architect, founder of Landprocess and the Porous City Network, joined the conversation to present Bangkok’s first new park in the city in 30 years: The 12-acre Chulalongkorn University Centenary Park.

Because Bangkok’s topography is flat, and because rains there are heavy and frequent, floods have become part of the daily life in the city. As such, for the Chulalongkorn University Centenary Park, Voraakhom implemented a design that modified the topography by tilting the park at 3 degrees, which allows it to funnel stormwater into a retention basin that can double in size during heavy rains.

Delta cities can be found all around the world. New York City, Tokyo, New Orleans, just to name a few, are slowly sinking as sea levels rise. But, as Voraakhom pointed out, there’s a systematic reason behind Bangkok’s sinking problem: Aside from the challenge that comes from building a city on top of a delta, the main issue stems from the fact that there is no more sediment coming from upstream because dams that create electricity are blocking the sediment flow.

READ ALSO: Q&A: SITES Certification, a Natural LEED Extension

What is our ambition for architecture?

Transitioning from molecular biology to architecture, Catherine Huang, partner at Bjarke Ingels Group, found that science and architecture share the same practice of experimentation. In architecture, these experiments are geared toward finding sustainable solutions. What’s more, both industries are equally ambiguous and even though finding the right answer remains the goal, it is more critical to be asking the right question, as that will determine the quality of the architecture.

Sustainability means being better for the environment but in a way that’s more enjoyable for the lives of its citizens, Huang said.

One notable project developed by Huang’s company is CopenHill, a tree-filled ski slope and hiking area, with a 278-foot-high artificial climbing wall, open all-year-round, with a design concept as if pulled out of a science fiction movie. The most intriguing aspect of this project is that it replaces the adjacent 50-years-old waste-to-energy plant with Amager Ressourcecenter (ARC), CopenHill’s new waste incinerating facilities integrate the latest technologies in waste treatment and energy production. The development embodies the notion of hedonistic sustainability with Copenhagen’s goal of becoming the world’s first carbon-neutral city by 2025.

Huang also presented the company’s Oceanix City concept that features floating villages that can withstand hurricanes. The design provides a habitable offshore environment in the event of rising sea levels, which are expected to affect about 90 percent of the world’s coastal cities by 2050. In addition to being constructed from locally sourced materials, such as wood and bamboo, renewable energy resources like wind and water turbines and solar panels are incorporated. Moreover, food production and farming would also be integrated and follow a zero-waste policy. And one of the major points of this concept design is that Oceanix City is an example of an affordable development that can be adapted to any culture.

Even though the three speakers live in different parts of the world and in different cultures, they shared the same goals: to change mindsets from sustainability being restrictive and expensive to an intuitive and creative design tool. Moreover, they all agreed that concepts from indigenous and natural systems and processes can make sustainable building more accessible and scalable.

You must be logged in to post a comment.