Can Real Estate Adapt to Historic Levels of Change?

Steeped in tradition and time-honored techniques, the real estate industry has thrived thanks to its dependability and cyclical nature, but powerful forces are creating disruption on an unprecedented scale.

By Samantha Goldberg

The MOD, a hypothetical Los Angeles cultural center designed by Gensler, shows how parking garages can be coverted to other uses as parking needs diminish. Garrett Rowland, courtesy of Gensler

Just about any real estate professional is likely to tell you that the industry can be slow to change.

As Steven Weikal, head of industry relations at the MIT Center for Real Estate, put it: “We have this multitrillion-dollar industry globally … and yet we still run it off of spreadsheets and PDFs.”

Steeped in tradition and time-honored techniques, the industry has thrived thanks to its dependability and cyclical nature, but powerful forces are creating disruption on an unprecedented scale.

Technology, of course, is the best-known source of disruption, profoundly influencing operations and strategy in all property categories. E-commerce is pushing retailers to adopt omnichannel strategies and retail owners to rethink tenant rosters while also creating a boom in distribution center development.

The office sector is also in transition as occupiers’ space, flexibility and connectivity needs evolve, while in the multifamily space, technology has opened the floodgates for a variety of amenities that residents expect owners to provide.

Generational shifts, too, are in play. Millennials have become the largest cohort, while the Gen-Z population is beginning to enter the workforce. At the same time, Baby Boomers are retiring later, and the population age 65-plus is set to nearly double by 2055, the Census Bureau estimates.

It’s impossible to predict how these trends will disrupt the real estate industry next, but adapting to them is vital to staying relevant and thriving. Meanwhile, forward-looking firms are taking notice of additional disruptors that will make their mark on 2018 and the years to come. In this special report, we explore four of those far-reaching trends.

Immigration’s import

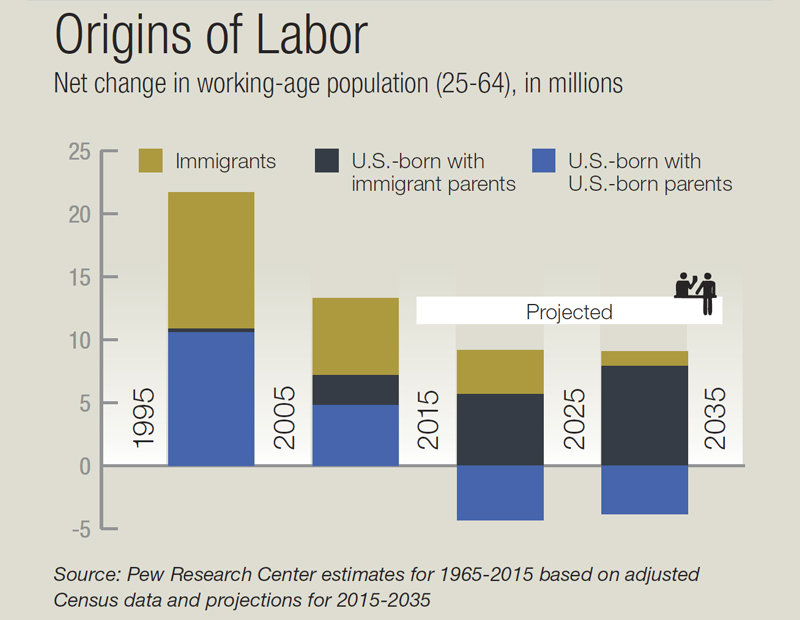

Though the impact of the Millennials and the aging of the population on real estate is well documented, immigration reform could be even more significant in the long run, argues Victor Calanog, chief economist & senior vice president at Reis.

Though the impact of the Millennials and the aging of the population on real estate is well documented, immigration reform could be even more significant in the long run, argues Victor Calanog, chief economist & senior vice president at Reis.

“If you tend to curtail immigrant populations from moving (into the U.S.), then you’ll have less of that productive slice of the worker population that you do need to support an aging population,” he explained. Labor shortages were already prevalent well before the announcement of November’s record-low 4.1 percent unemployment rate.

According to an August 2017 survey from Autodesk and the Associated General Contractors of America (AGC), 70 percent of construction firms experienced difficulty filling the hourly craft positions that represent the bulk of construction industry jobs. The shortage suggests that restrictions on immigration could further tighten the labor market and slow development.

“In the short term, fewer firms will be able to bid on construction projects if they are concerned they will not have enough workers to meet demand,” AGC CEO Stephen Sandherr commented.

States like California, Texas and New York—which together account for 46 percent of the nation’s 43.2 million immigrants, according to the Pew Research Center—would likely be hit hardest.

In addition to impacting the workforce, more restrictive immigration policies could hinder multifamily growth. Immigrants have accounted for nearly 28 percent of all household growth over the past 20 years and have aided in the recovery of many housing markets hurt by the Great Recession. With average population growth expected to slow from 0.9 percent per year between 2000 and 2010 to 0.7 percent annually between 2016 and 2030, according to a recent study commissioned by the National Multifamily Housing Council and the National Apartment Association, immigration will be necessary to fuel multifamily housing demand. Immigrants have a higher propensity to rent than the population as a whole and typically remain renters longer, the study showed.

Health-care cures

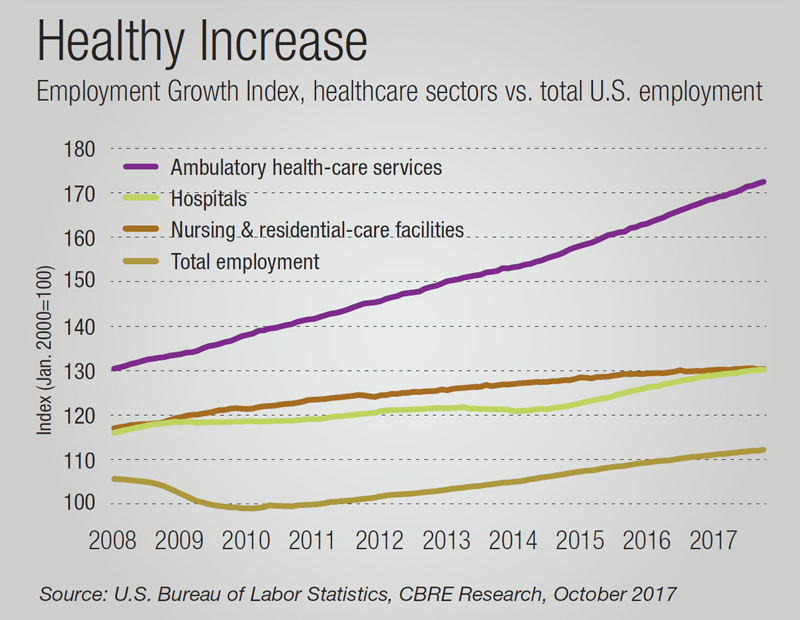

While a wave of retirements among Baby Boomers may be contributing to the labor shortage, it is a boon for health-care real estate fundamentals. Investors are taking notice, and transaction volume climbed from $4 billion in 2010 to $10.2 billion in 2016, according to CBRE’s 2017 medical office building (MOB) report. Absorption has outpaced new supply for the past seven years, resulting in steadily declining vacancy rates that reached 8 percent in the first quarter of 2017.

While a wave of retirements among Baby Boomers may be contributing to the labor shortage, it is a boon for health-care real estate fundamentals. Investors are taking notice, and transaction volume climbed from $4 billion in 2010 to $10.2 billion in 2016, according to CBRE’s 2017 medical office building (MOB) report. Absorption has outpaced new supply for the past seven years, resulting in steadily declining vacancy rates that reached 8 percent in the first quarter of 2017.

Despite uncertainty surrounding health-care policy, owners are expanding and transforming properties to serve an aging population, noted Spencer Levy, CBRE Americas head of research. Only 20 years ago, health-care services were largely located on hospital campuses; today, suburbs or secondary markets with large populations of seniors tend to be the locations of choice.

Facilities that bring services closer to patients—freestanding ambulatory-care centers, standalone emergency clinics and large MOBs, for example—are in high demand, according to Marcus & Millichap’s second-half 2017 MOB report. Medical office design is also changing: Online documents are reducing the space required for storage, and evolving uses call for more flexible floor plans.

As the industry navigates a mature recovery, many investors are eyeing health-care real estate, which Levy expects will become a growth engine, particularly in secondary and suburban markets, where job drivers tend to be less diverse.

Quality search

Health care is a much-discussed issue associated with the aging population, but another impactful trend is the budding preference for aging in place.

Health care is a much-discussed issue associated with the aging population, but another impactful trend is the budding preference for aging in place.

Vacancy rates among senior-care facilities average 8.4 percent nationally, compared to 4.5 percent for the multifamily sector, Calanog noted, a sign that the late-1990s influx of product outstripped demand. “People are living longer and living higher-quality lives, which means they’re delaying demand for assisted-care homes,” he observed. By contrast, vacancy at memory-care and skilled nursing facilities is declining because “at that point it’s no longer a choice, it’s a need,” he related.

Baby Boomers are also bucking tradition by retiring later and living independently longer, further bolstering the multifamily sector and constraining senior housing. By 2024, people age 65 to 69 will comprise 36 percent of the labor market, according to the BLS.

The implications are clear: To accommodate seniors choosing to age in place, developers must expand their strategy beyond the often-discussed Millennials. Project sponsors and investors will need to provide designs and amenities to offer seniors an attractive quality of life and facilitate interaction across age groups, according to a 2017 Capital One-MIT Center for Real Estate report.

“Developers are now bringing in urban-like amenities, even to suburban developments,” Calanog observed, citing retail and entertainment as examples. “All of these amenities add up to make the lifestyle today really unrecognizable to people 20 years ago.”

Gear shift

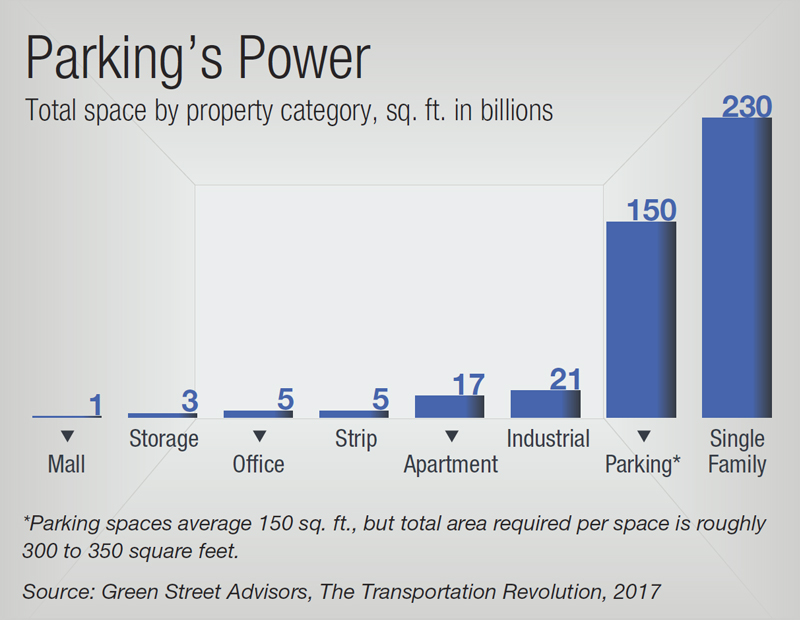

While seniors typically move out of their primary residences once they lose mobility, driverless cars could “change that calculus,” Levy noted. The concept may still seem unfathomable, and the timing remains unclear, but all signs indicate that self-driving cars are on the road to reality. Makers of autonomous vehicles (AVs)—like Google’s Waymo, Tesla and General Motors, as well as several startups—are already testing their products on public roads. Forward-thinking sponsors are taking note. In November 2017, Optimus Ride and developer LStar Ventures announced a first-of-its kind partnership to provide residents of Boston’s Union Point development with access to AVs. Public officials are getting on board, as well. Companion bills moving through Congress would allow 80,000 to 100,000 AVs on the road annually and prohibit states from imposing regulatory roadblocks. Supporters say AVs will cut traffic congestion dramatically, reduce accidents and decrease driving costs; skeptics argue that safety and security haven’t been fully addressed.

While seniors typically move out of their primary residences once they lose mobility, driverless cars could “change that calculus,” Levy noted. The concept may still seem unfathomable, and the timing remains unclear, but all signs indicate that self-driving cars are on the road to reality. Makers of autonomous vehicles (AVs)—like Google’s Waymo, Tesla and General Motors, as well as several startups—are already testing their products on public roads. Forward-thinking sponsors are taking note. In November 2017, Optimus Ride and developer LStar Ventures announced a first-of-its kind partnership to provide residents of Boston’s Union Point development with access to AVs. Public officials are getting on board, as well. Companion bills moving through Congress would allow 80,000 to 100,000 AVs on the road annually and prohibit states from imposing regulatory roadblocks. Supporters say AVs will cut traffic congestion dramatically, reduce accidents and decrease driving costs; skeptics argue that safety and security haven’t been fully addressed.

Of note, trucks are not covered in the bills, largely due to concerns about the loss of as many as three million driving jobs, notes a Green Street Advisors report. But the prospective benefits of autonomous trucks can’t be ignored. Without needing to stop for breaks, the vehicles would drive longer and deliver goods faster, which could impact the design and location of distribution centers.

While the report forecasts that mass adoption of AVs is still some way off—beginning in 2030 and complete by 2045—developers are beginning to shift their building strategies, particularly with parking structures. The U.S. has more than one billion parking spaces, but AVs could cut the number in half over the next 30 years.

Some cities are looking ahead, too. Buffalo, N.Y., and Santa Monica, Calif., have eliminated parking requirements for new development, noted Randall Rowe, chairman of investment firm Greene Courte Partners. Parking is typically “a drag on the economics of affordability,” he said. Reducing parking could trim construction costs and open opportunities to other uses.

Rowe doesn’t believe driverless cars will eliminate parking altogether, but he asserts that the future of parking—and cities—will look much different. He foresees AV “nesting facilities,” marked by larger capacity, lower height and less light than conventional parking because they won’t need to accommodate people. He also expects standalone garages and surface lots to be easily converted, but parking embedded in mixed-use structures will be more challenging. Possible solutions for embedded parking are converting them to self-storage or car servicing facilities. He also expects street parking to be converted to AV pick-up locations.

Some innovative developers and designers are already considering how to build convertible parking structures. Gensler has designed several projects with flexible parking, such as 84.51° Centre in Cincinnati, which includes three above-grade levels of parking adaptable to office space.

“We are designing the next generation of buildings and airports, incorporating future-proofing design, in which parking structures are designed for flexibility and adaptive reuse,” affirmed Gensler Co-CEO Andy Cohen. “There’s a tremendous opportunity to take our cities’ streets back and have them reclaimed for people.”

Rowe noted, however, that this strategy costs about 50 percent more than constructing purpose-built garages. With that in mind, some municipalities have floated the idea of offering zoning bonuses to developers to help offset the additional expense.

Queue space

Gensler designed the above-grade parking at 84.51° Centre, the headquarters of consumer analytics firm 84.51° in downtown Cincinnati. To allow for potential conversion, parking levels have the same dimensions and structural detailing as the office floors. Image by Garrett Rowland; courtesy of Gensler.

In addition to impacting parking design, self-driving cars will likely prompt retail owners to build out larger pick-up/drop-off areas like those at Las Vegas casinos, Levy noted, a trend we’re already observing as a result of ride-sharing vehicles.

Cities and real estate players will have to work on queuing solutions, however, to alleviate congestion at spots where people and vehicles meet, Rowe pointed out, raising the larger question of how to modify the nation’s roads to accommodate AVs.

The White House has announced intentions to boost infrastructure investment, and the private sector is taking action. In 2017, Blackstone launched a $40 billion fund with $100 billion in purchasing power. Still, the road ahead will be far from smooth.

“As we all know, projects simply take too long in the U.S. to get done today. I think there is a lot of work that’s being done … trying to streamline the approval process in the U.S.,” said Sean Klimczak, Blackstone’s global head of infrastructure, speaking at a recent conference sponsored by New York University’s Schack Institute of Real Estate.

Regulatory and legislative hurdles will likely determine how deeply many of today’s biggest disruptors will emerge in real estate, Levy predicted. In the meantime, the industry’s decision-makers will have to rethink their strategies to anticipate the changes ahead while also serving their target demographic groups.

“In this day and age, the challenge for real estate developers and market participants is to convince people that place still matters,” Calanog observed. “And that their place—because real estate is about place—is the place to be.”

Originally appearing in the CPE-MHN Guide to 2018.

You must be logged in to post a comment.