CMBS Deals Continue in Face of Uncertainty

Issuances have rebounded after slowing to a standstill, but billions of dollars of troubled loans weigh on the market.

The early days of spring following the onset of COVID-19 and the initial economic lockdowns delivered a shock to the commercial mortgage-backed securities market. CMBS bond spreads widened dramatically as investors became more selective, and transactions slowed to a standstill before relative stability and modest activity returned.

Yet the saga is far from over. A growing number of lodging and retail property loans are in forbearance or special servicing, portending a wave of defaults, foreclosures, or discounted loan payoffs and sales. Because the mortgages are nonrecourse, many underwater borrowers can simply walk away from the properties by mailing the keys to the lender.

As a result, the CMBS space could eventually provide significant distressed investment opportunities, acknowledged Lisa Pendergast, executive director of the Commercial Real Estate Finance Council, a New York-based financial trade association.

“As soon as we got a sense that COVID-19 was going to last longer than a month or two, investors were very quick to assemble capital and prepare for whatever distress might come,” she said. “The good news is that we’ll have more buyers vying for opportunities, so the period of distress could be shorter than normal.”

Experts note, however, that a backlog of troubled loans piling up on the desks of CMBS special servicers could create a prolonged period of instability. Uncertainty is fueled by the complexities of bonds, the potential for litigation between holders of different CMBS tranches, and social distancing rules that are delaying the appraisals and court filings to resolve bad debt issues.

“When these financial packages were built, one thing never considered was a cataclysmic economic event,” said Scott Stuart, CEO of the Turnaround Management Association, a Chicago-based organization of turnaround professionals. “And these securitized loans are not designed to be easily modified or restructured, so it really creates uncertainty.”

Issuances rebound

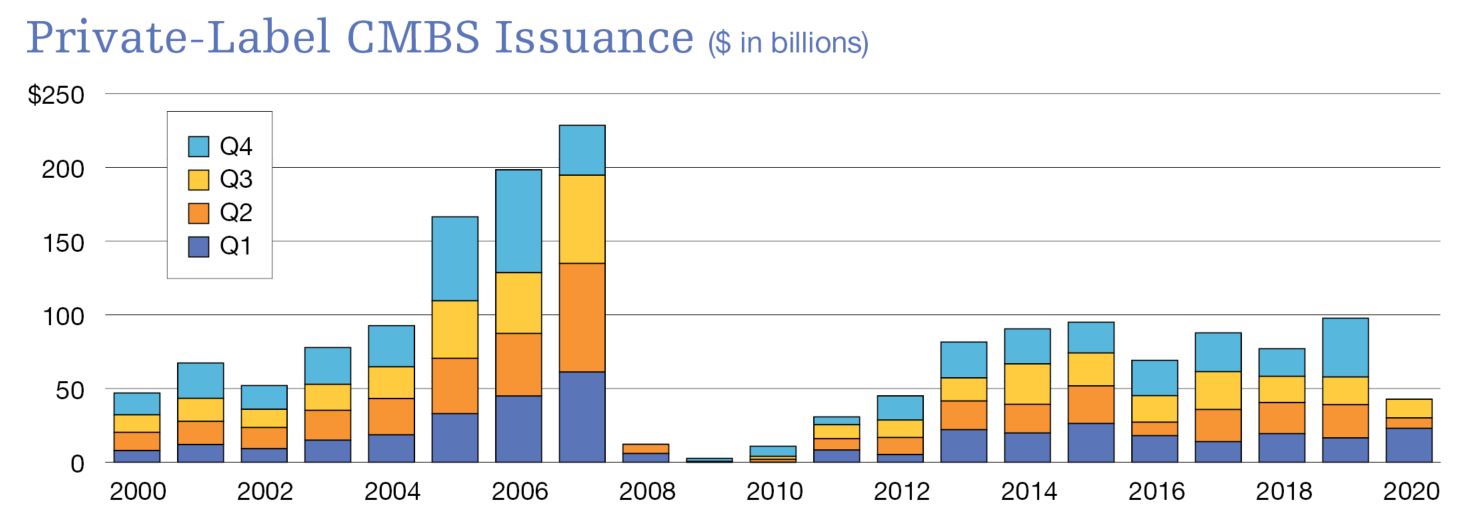

Despite questions about the future of existing CMBS loans, new securitizations have picked up to a degree, largely led by the refinancing of maturing CMBS debt. CMBS issuances totaled $100 billion in 2019, and, prior to the onset of the pandemic and subsequent lockdowns, the industry anticipated about the same level of activity this year, Pendergast said.

Now the industry expects to see a 25 percent decline in CMBS issuances from 2019. As of early October, securitizations had reached $44.5 billion, which was $14.2 billion shy of the mark set for the same period in 2019, she added. Some $10 billion in loans are set to mature by the end of the year and $17.6 billion in 2021. As long as maturities don’t fall in the hard-hit lodging and retail sectors, refinancing capital is largely available, Pendergast said.

“We’re only in October and anything could happen,” she explained. “But right now, it seems like there’s an appetite for new CMBS deals coming to market.”

Indeed, the primary problem for bond investors is that they have too few deals from which to choose, added Gerard Sansosti, an executive managing director with JLL in Pittsburgh. As a result, transactions are oversubscribed, he added, and CMBS bonds have tightened considerably. AAA CMBS bond spreads were around 90 basis points in early October, for example, after ballooning to some 320 basis points amid the pandemic chaos in April, Pendergast said.

Among other deals, Wells Fargo Commercial Mortgage Securities recently led the issuance of 54 loans on 92 properties totaling $598.6 million, according to filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission. Multifamily, mixed-use and office properties made up about 61 percent of the CMBS pool, while industrial, retail and self storage assets roughly rounded out the balance. A downtown Seattle office building, a Bronx, N.Y., apartment portfolio, and an office and retail building in Manhattan secured the three largest loans.

“Given the fact that yields are so low right now, anything that has some spread is getting snapped up pretty quickly,” said Joe McBride, head of commercial real estate finance for Trepp.

Rising distress

Meanwhile, funds that invest in distress, which have raised billions of dollars over the last several months, are looking to buy-up troubled loans for pennies on the dollar. CMBS special servicers are already marketing some loans after owners walked away from the properties to avoid foreclosure, including a $6.3 billion mortgage tied to the 990,000-square-foot Southland Mall in suburban Miami.

Still, experts anticipate that it could take some time before a substantial wave of CMBS distress begins to hit the market as borrowers and special services grind through the resolution process. Jacob Reiter, president of Verde Capital, a real estate private equity firm based in Conshohocken, Pa., plans to focus on distressed lodging CMBS loans. Reiter expects to see discounts of up to 30 percent in the assets in which he’ll be interested.

“Right now, there’s a lack of clarity of where we are in the cycle,” he added. “But distress hasn’t been fully realized, and therefore, pricing hasn’t been fully discounted. We think that begins to happen in mid-to-late 2021, based on conversations with special servicers and people who own distressed assets.”

While Trepp notes that CMBS delinquencies ticked down three months in a row to 8.9 percent in September, some of that improvement was a result of delinquent loans technically becoming current after special servicers agreed to forbearance.

Thus, the telltale of the CMBS market’s health resides in forbearance numbers and the special servicing rate. As of September, some 800 CMBS loans totaling $31.2 billion were in forbearance, about twice the number and dollar amount in July, according to Trepp. Lodging and retail property mortgages made up roughly 92 percent of the loans in forbearance.

Similarly, 26 percent of lodging and 18.3 percent of retail CMBS loans were in special servicing in September, both of which represented an increase of about one percentage point over August and the highest levels ever recorded, according to Trepp. The overall CMBS special servicing rate hit nearly 10.5 percent in September, an increase of 44 basis points over August.

“We’ve seen borrowers throw in the keys, and I see note offerings in my inbox every day,” McBride said. “If it wasn’t for forbearance, it would be happening more.”

Restrictive rules

In addition to the overwhelming number of problem hotel and retail loans in the special servicing pipeline, the inability to price assets is contributing to a delay in loan sales and discounted payoffs, said Shlomo Chopp, managing partner with Case Property Services, a New York-based real estate advisory that specializes in restructurings and turnarounds.

But as special servicers get a grasp on the backlog of work, he predicts that the process to resolve the troubled loans will happen quickly because of changes made to CMBS rules following the financial crisis. Back then, borrowers could try to prevent foreclosures through litigation. Today such an action is covered under “bad boy” provisions and will trigger recourse. Ultimately such a measure could dampen the prospect for widespread loan modifications.

“To deal with these problems last time, we would litigate with the lenders and drag things out for a year until we got a new appraisal, and then we would educate the lender and appraiser on the issues of the property,” explained Chopp, who is also managing partner for investment management firm Case Equity Partners. “But borrowers can’t do that now, and we’re going to see an inordinate number of people losing their properties.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.