Cutting Carbon Emissions Through Electrification

A new report from the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy finds that energy-efficient electric heat pumps cut commercial buildings’ greenhouse emissions by 44 percent.

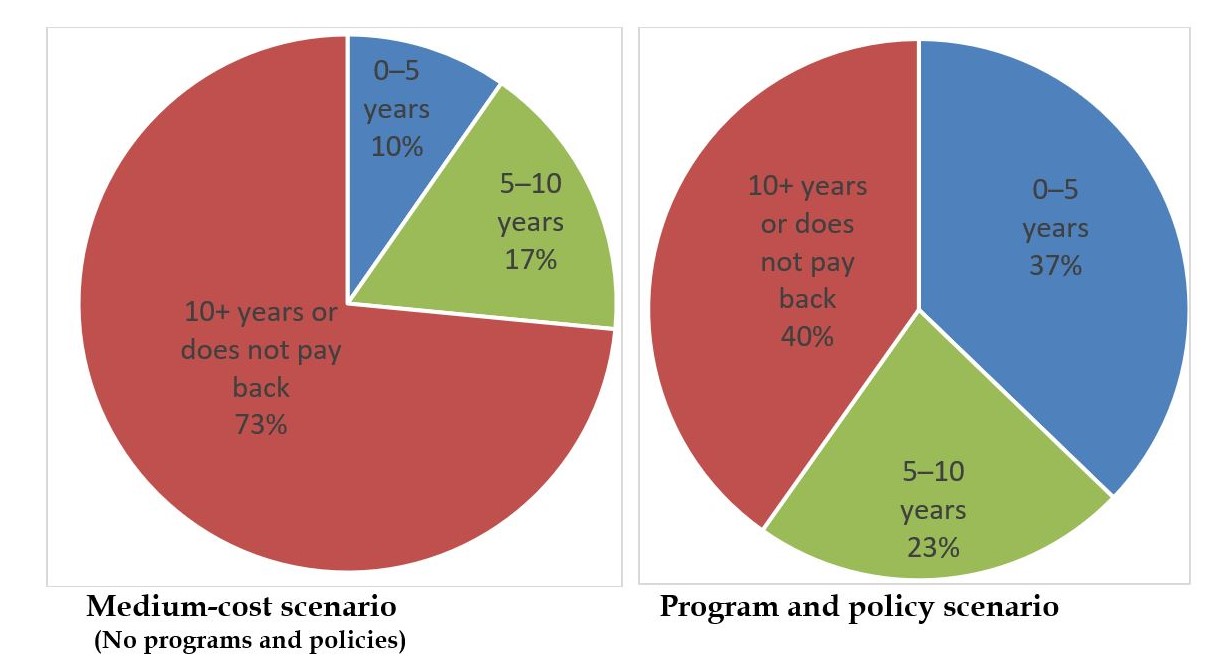

Distribution of the simple payback period by floor area for converting gas-fired rooftop systems, furnaces, space heaters, and small boilers to heat pumps when existing equipment needs to be replaced. Chart courtesy of ACEEE

Commercial buildings that replace their gas-burning heating systems with energy-efficient electric heat pumps could reduce their total greenhouse emissions by 44 percent, according to a new report by the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy.

The ACEEE report, titled Electrifying Space Heating in Existing Commercial Buildings: Opportunities and Challenges, also found that about 27 percent of commercial floor space heated with fossil fuel systems could be electrified with a simple payback of less than 10 years without any rebates or carbon pricing. If policymakers enact a package of public investments, incentives and carbon pricing policies, the proportion of commercial building space that could be electrified with a simple payback of less than 10 years would more than double, rising to 60 percent.

READ ALSO: Raising the Bar for Greenhouse Gas Reduction

To get to net-zero emissions, most commercial buildings’ heating systems would need to be upgraded with electric heat pumps, Steven Nadel, ACEEE executive director and report co-author, said in a prepared statement. The upgrade is often a tough sell for building owners when the payback periods are long, so policymakers would need to make major investments in incentives for the technology for it to be adopted widely, Nadel noted.

While acknowledging that, during the Trump administration, the federal government was “not as open” to considering incentives, report co-author Chris Perry, research manager in the ACEEE buildings program, said it’s a little too early to know what to expect from President-elect Biden’s administration on any incentives. If changes are made, Perry said, this could be a combination of federal government, state and/or local incentives.

According to Perry, there were two important drivers for undertaking the study. “We’re seeing a lot of movement from cities and states that are either implementing of starting to consider electrification policies. It seemed important to help them by giving them that data—what are the economics and what do you need to do,” Perry told Commercial Property Executive.

He also noted that most of the research on the electrification of buildings has examined residential and industrial assets. “Commercial is more complex and more diverse and we have not seen as much research. We saw a need to do an analysis,” Perry said.

The report explored the possibility of converting packaged heating systems, furnaces, boilers and space heaters for a range of small-to-medium buildings across all regions.

The three most-common scenarios analyzed were:

- converting rooftop packaged systems that use natural gas to rooftop electric heat pumps

- converting gas furnaces to heat pump systems

- converting gas boilers and space heaters to either ductless heat pumps in smaller buildings or variable refrigerant flow (VRF) heat pumps for medium-size buildings.

The report authors also provided options on converting larger buildings using chillers and boilers to various types of large heat pumps but did not have sufficient data to do an economic analysis of the larger buildings. Those are often done as part of major building renovations.

According to the report’s findings, the buildings with the best paybacks are more likely to be located in warmer climates such as in the Southern U.S. and the Pacific region, where less space heating is needed. Buildings likely to have better-than-average conversion economics often have medium-to-high operating hours, such as health care, food, retail and offices. Nadel and Perry caution those are general tendencies and the economics of conversion will vary by site and other factors including energy use and costs.

Chris Perry, Research Manager at ACEEE. Image courtesy of ACEEE

Even with policy support and incentives, electrification in some buildings such as those with complex HVAC systems or in cold climates may still be challenging, the ACEEE report notes. Some of the case studies indicated that for some commercial buildings the owners may electrify most of the load but continue to have a fuel-based backup for very cold days.

“The goal is 100 percent but if we can get to 80 or 90 percent in certain buildings, we’d still have really great carbon emissions savings,” Perry said.

Among the report’s recommendations to boost electrification in commercial buildings are:

- policymakers improving incentives and instituting a fee on GHG emissions

buildings owners using other energy efficiency measures to reduce heating load when they install heat pumps

- policymaker investing in research and development to help reduce costs of heat pumps

- requiring or encouraging building owners to get heat pump bids whenever a fossil fuel heating system needs replacement.

Electrification Followers

The report’s findings were hailed by other experts, including Cliff Majersik, director of market transformation at the Institute of Market Transformation.

“This study shows how important electrification is to lowering America’s greenhouse gas emissions, and the level of policy and investment that will be required to electrify at the pace required to prevent catastrophic climate change,” Majersik said.

He noted the report also provided “strong evidence that, to succeed, America’s strategy for decarbonizing” must take a four-pronged approach—energy efficiency, renewable energy, electrification and demand management—to minimize impacts on the electric grid.

Sean Denniston, senior project manager at the New Buildings Institute, said the results highlight the important connection between efficiency and electrification.

“Electrification allows the adoption of high-performance heat pumps that can be three to four times more efficient than their gas and electric resistance counterparts, and the efficiency gains are what drive the energy, lifecycle cost and GHG savings,” he said.

Denniston noted that the analysis includes the cooling savings that often come with heat pump retrofits, providing important considerations for resiliency in commercial buildings.

“We know that poor air quality from pollution and wildfires will mean higher demand for mechanical cooling, especially in regions that have historically depended on natural ventilation for cooling. More efficient heat pump cooling systems will reduce the energy demand from existing buildings and cut the additional energy demand from new cooling systems,” Denniston said.

You must be logged in to post a comment.