Debt Funds That Can Continue to Hunt for Deals

The pandemic and lockdowns have largely sidelined alternative lenders that depend on leverage, but those that use their balance sheets remain active.

Prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, debt funds had carved out a solid niche in the commercial real estate lending space. But as has been the case with other lenders, many debt funds moved to the sidelines or began tending to troubled loans after the economic lockdown brought a halt to commercial real estate sales and created distress overnight. Some, however, remain in the market. What’s the difference between the two? Leverage.

In particular, debt funds that relied on warehouse lines faced debilitating margin calls as the crisis unfolded. Meanwhile, those that replenished their capital by selling part of their loans to banks or in the collateralized loan origination market saw those sources dry up, too. Some of the largest debt funds, including TPG Real Estate Finance Trust, Colony Credit Real Estate and Granite Point Mortgage Trust, have had to sell assets to improve their liquidity positions.

“Many leveraged players saw their loans blow up and had to walk away from a lot of equity,” said Gary Bechtel, CEO of Red Oak Capital Group, a debt fund based in Grand Rapids, Mich. “But the funds that didn’t use leverage remain in the market and continue to raise and deploy capital.”

Flexible but pricey

Debt funds are private pools of non-regulated capital that typically provide borrowers with short-term loans for construction, value-add projects or other situations that require gap or bridge financing. Debt funds generally offer higher loan-to-value ratios, speedier execution and more flexible terms than banks. But borrowers pay upwards of 250 basis points more for debt fund capital. Leveraged funds can generate annual yields of 12 percent to 15 percent, while balance sheet debt funds deliver 9 percent to 11 percent.

Although debt funds make up a small percentage of the overall commercial real estate lending market, the space has attracted numerous players over the past few years, including separate accounts held by life insurance companies and banks. Using bridge lenders as a debt fund proxy, Bechtel has tracked the growth of these alternative lenders. In 2019, the number peaked at more than 360, up from 150 in 2015, he said. Today that number has likely dropped to less than 200, he estimated.

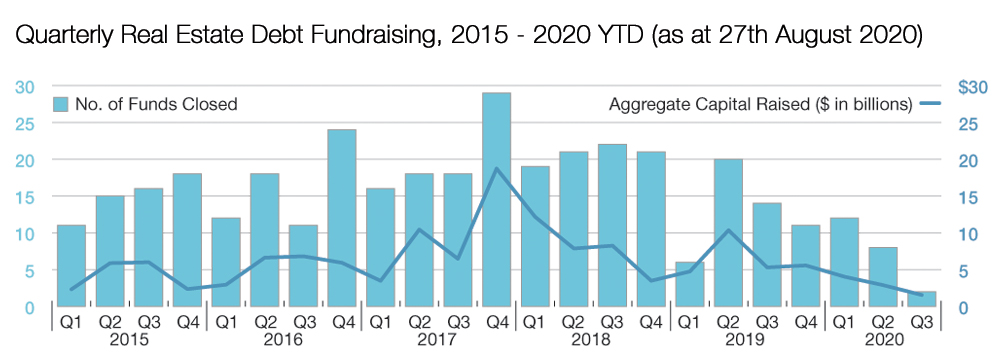

What’s more, 91 real estate funds raised more than $39 billion in 2017, the high water mark in terms of dollar volume over the past five years, compared with 60 funds that raised nearly $16 billion in 2015, according to Preqin. Only 20 funds raised about $7 billion in the first two quarters this year.

Douglas Weill, managing partner for Hodes Weill & Associates, a real estate capital advisory firm based in New York, suggested that debt fund capital raising could remain muted for the next several quarters. Institutional investors his firm works with that regularly invest in the funds are looking to be more aggressive in this environment, he said.

“In our view, institutions have dialed up their return and risk profile – they’re a little less interested in a strategy that’s returning 8 to 10 percent today,” he said. “They think they should be playing more offense and focusing on equity and distress.”

Deal hunters

Debt funds that finance deals off their balance sheets remain active, although they have become more selective and conservative. Before the pandemic, debt fund borrowers could secure financing with an interest rate of 5 percent to 6 percent based on the 30-day London Inter-bank Offered Rate of around 1.7 percent, said Joseph Iacono, CEO and managing partner for Crescit Capital Strategies, a New York-based alternative commercial real estate lender. Today that interest rate is as much as 8 percent or higher, even though LIBOR is roughly 150 basis points lower.

“The risk premium has gone up,” he explained. “Debt funds are not putting as much money out, and they are charging more for the money they do put out, and they’re going to be very picky about where they put that money.”

While debt funds have long favored a value-add strategy that profits from significant increases in rental rates or property values, pursuing those deals today makes less sense given the uncertainty about the future. Instead, the funds are financing projects in need of light improvements or leasing.

Debt funds are also seeing more opportunities to make construction loans as banks have pulled back, said Toby Cobb, co-founder and managing partner of 3650 REIT, a commercial real estate lending and investment management services firm. Still, even though lenders can demand better terms for the loans to mitigate risk, they’re more difficult to make compared with loans on transitional assets, he added.

“Cost overruns and mishaps are a real component of being a construction lender,” Cobb said. “And, right now construction loans are more complicated–it’s not easy to put out capital because of questions surrounding how long the pandemic lasts and whether we should be building anything at all.”

To the rescue

To take advantage of more opportunistic situations, some funds are providing “white knight” capital to stressed hotel and retail property owners, who are repurchasing existing debt at a 20 percent to 40 percent discount from their lenders.

In Colorado Springs, for example, Dallas-based Revere Capital this spring provided the owner of a 360,000-square-foot shopping center with $19.6 million, which funded a $22 million payoff of the $34 million loan held by a mortgage REIT as well as a reserve account for leasing costs. The REIT had seen its share price plummet about 70 percent since the lockdown and needed to improve its liquidity position to meet a margin call from its repo lenders, said Clark Briner, founder and principal of Revere Capital.

“Discounted payoffs were a great business between 2009 and 2012, and we’re seeing them return,” said Briner. “Banks and other lenders are trying to monetize their allocations in the retail and hospitality space, if they can, because they don’t know how the coronavirus is going to affect those assets.”

Acres Capital, based in Westbury, N.Y., is considering similar deals in the hospitality sector. One owner of 55 hotels has an opportunity to buy back loans at a discount but can’t find conventional financing, said Mark Fogel, CEO of Acres. That kind of dynamic should open a path to one or two well-located hotels with high-quality flags, he added.

“Lenders just don’t want to dig a deeper hole by laying out more money and not get paid debt service,” Fogel said. “They’re thinking that they can get their best price now, before a flood of distressed notes begins to hit the market.”

Debt funds clearly recognize these potential opportunities in such an environment, and with forbearance periods ending, they’re likely to become even more plentiful. Whether the funds can take advantage of them, however, depends on their ability to look ahead rather than behind.

“The whole idea of playing offense today depends on the extent to which a fund is leveraged and what condition your loans are in,” said Jack Gay, global head of commercial real estate debt for Nuveen Real Estate. “If you have a lot of leverage and more challenged asset classes like hotels and retail, then certainly you’re focused on liquidity and are playing defense instead of offense.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.