Debunking Myths About Sustainable Sites, Climate Adaptation at Greenbuild

What are the most common misconceptions about the Sustainable Sites category in LEEDv4.1 and the ability to adapt to natural disasters?

Transforming the ways buildings and communities are designed, built and operated has been at the forefront of the U.S. Green Building Council’s work for nearly three decades, along with resilience—a concept that, in this industry, relies heavily on the ability to prepare for, absorb, recover from and adapt to adverse events.

But, in order to be able to adapt, we first need to understand the tools and mechanisms we can use to build a safer and more sustainable future, while overcoming a variety of obstacles related to climate change. With that purpose in mind, a group of sustainability experts gathered on the last day of Greenbuild virtual to debunk the top myths and misconceptions about the Sustainable Sites category of the current version of LEED and climate adaptation.

READ ALSO: Shaping a Regenerative Future at Greenbuild 2020

Karema Seliem, LEED specialist at USGBC, moderated the panel, which brought together Rachel Nicely, sustainable program manager at Sustainable Building Partners; Mikel Wilkins, director of sustainability at TBG Partners; and Stephane Larocque, chief operating officer at Autocase.

Resilience Is Primarily About Mitigation

One of the most common questions that arise among industry experts is: What is the current state of the market when it comes to absorbing and adapting to natural hazards? “The market is really shifting and there’s a big focus on how we plan and design our sites to start addressing these climate action goals,” Wilkins said, talking about the situation in major Texas cities.

In Dallas, for example, building planners and designers find inspiration in nature. Native and low-maintenance plants play a critical role, maximizing the tree canopy to naturally keep temperatures lower. In addition, the costs of cooling a building can be lowered by incorporating green roofs or—when plants can’t be used to absorb the heat from the sun’s rays—using materials that reflect rather than absorb rays, Wilkins said.

Due to heightened development activity over the past few years, the impact of flooding and drought has also been intensifying in the Dallas area, as well as in other parts of the country. “We have this need to reclaim water wherever it can be found,” Wilkins said—and one of those obscure sources of water is condensate, a byproduct of air conditioning units that are used in pretty much every building in the area. Wilkins also mentioned that stormwater management needs to be multi-purpose and serve as a “local amenity”.

Another critical area of action for the city of Dallas, Wilkins said, has been protecting, restoring and enhancing its green spaces, trees and ecosystems to help improve air quality and public health. All of these aspects work hand in hand with designing healthy building codes, transit and remote work incentives and enhanced transportation network.

Reduced Carbon Emissions Can Only Be Achieved Through Energy, Materials and Transportation

The Sustainable Sites credits for the current version of LEED can address adaptation in more than just those three ways. “Without adaptation, we can’t properly mitigate carbon emissions,” Nicely reiterated, and strategies presented in the SS credits present substantial opportunities for adaptive design. All development projects can receive credits for:

- site assessment

- protecting or restoring the habitat

- open space

- rainwater management

- heat island reduction

- light pollution reduction.

These credits support ecosystem-based adaptation strategies in the conceptual design phase to create a more cost-effective site. “In the updated LEEDv4.1 program, the SS requirements are more approachable and better encourage projects to use proactive rather than reactive strategies to better prepare for the damaging impacts of climate change,” Nicely said. For example, the new pollinator habitat component, and no longer excluding the green roof compliance based on project size are too important changes designed to protect and restore habitat. In addition, rainwater management thresholds and definitions are more manageable and achievable regardless of the climate zone in which a project is located.

Site Assessment and Analysis Predesign Are Cost Prohibitive and Unimpactful

Various adaptation strategies can be used in the conceptual design phase to create a more cost-effective development site. The most impactful tool is using an integrative design process, Nicely said. “If the process is truly integrative, it involves an early goal-setting meeting to really set the tone for project teams who need to focus their design effort,” she added. This approach works well with the site assessment credit and the hazard assessment credit from the resiliency pilot credit.

In the site assessment phase, for instance, the solar exposure and orientation can be reviewed, but using that piece of information to design based on the future heat island and impact is equally important. “The most impactful design decisions are made early,” Nicely noted.

Furthermore, according to Larocque, the cheapest way to achieve a specific LEED goal is not necessarily the best way. This is where the cost-benefit analysis comes in handy—and projects can be awarded pilot credits that can push up a project’s total score. And from a planning and design perspective, there are several opportunities to minimize costs in the long term. “We should always be mindful of the monetary costs, obviously, but never so single-mindedly that we ignore the impact on a community’s physical and mental health, on social connectedness and equity or on ecological integrity,” Wilkins pointed out.

The Costs of Providing, Restoring and Maintaining Green Space Outweigh the Benefits

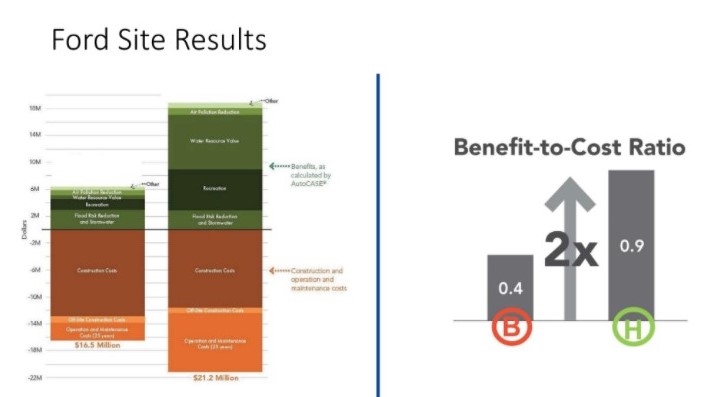

To debunk this myth, Larocque used the example of a former Ford factory site in St. Paul, Minn., which the local authorities wanted to transform in one of the most sustainable neighborhoods in the U.S. The 135-acre industrial site is located above the Mississippi River bluffs and is connected to Hidded Falls Regional Park. Larocque’s company helped the developers compare different investment options, including transportation and stormwater planning.

The “greener” investment alternative, which was slightly more expensive, featured the restoration of a stream that was a potential waterfall recreational area. Larocque added that the additional benefits far outweighed the additional costs for this project.

Green Infrastructure is Only About Mitigating Flooding

Flood mitigation is indeed a crucial aspect of green infrastructure projects, but it’s not the only one. Green roofs and public plazas help increase property values and rent prices, generating more revenue for the owners, landlords and ultimately the city, while adding recreational space to be enjoyed by the people, according to Wilkins. Furthermore, “what functions as green infrastructure (in some places) also functions as a restorative community hub and a local food source,” Wilkins said, talking about the planned redevelopment of an old service facility in the poverty-ridden Bonton community of South Dallas, Texas, that was re-imagined as a regenerative farm and a homeless rehabilitation center.

In another example, Wilkins talked about Denton Creek in Texas, where mixed-use areas and natural systems were connected to generate educational and recreation opportunities through enhanced habitat and water quality.

Sites Don’t Provide the Opportunity to Measure Performance

One of the SS Technical Advisory Groups that establishes the goals for future LEED is currently evaluating a number of tools that offer a way to quantify the carbon footprint of the landscape and the hardscape design, according to Nicely.

Two of these tools are i-Tree, which was developed by the USDA Forest Service, and Climate Positive Design’s Pathfinder, which helps reduce carbon footprints and sequester more carbon. “Each tool provides a way to quantify the impact from the landscape and the site features” Nicely said.

The carbon sequestration pilot credits that the SS TAG is currently developing will provide the opportunity to measure performance by looking at the embodied carbon of the site materials and at the sequestration properties of the vegetation for the overall impact.

You must be logged in to post a comment.