Digital Twins: The Ultimate Sustainability Consultant

When combined with AI, these technologies can create greener buildings—and help operate them, as well.

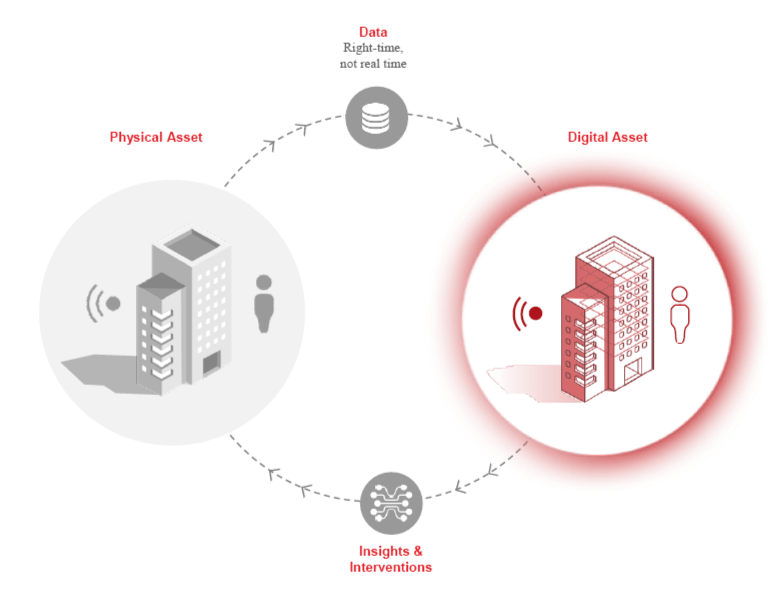

Digital twins have been on the radar of the building industry for some time, particularly for those focused on lowering the carbon intensity of the built environment. These real-time virtual models of commercial properties allow professionals to understand and interact with nearly every aspect of a property throughout its lifecycle. But the rapid acceleration and adoption of artificial intelligence are making these dynamic clones even smarter and more influential.

When used alongside reliably sourced and effectively exploited data, today’s digital twins provide an unprecedented degree of insight and control over a building’s construction and its day-to-day operations, as well as the ability to delegate some functions to a machine with instantaneous access to millions of potential data points.

“In very short order, what you have is an incredibly advanced building engineer that can monitor and operate your building on a 24/7 basis, never looking away,” said Jade Dauser, corporate real estate technology leader at Ernst & Young.

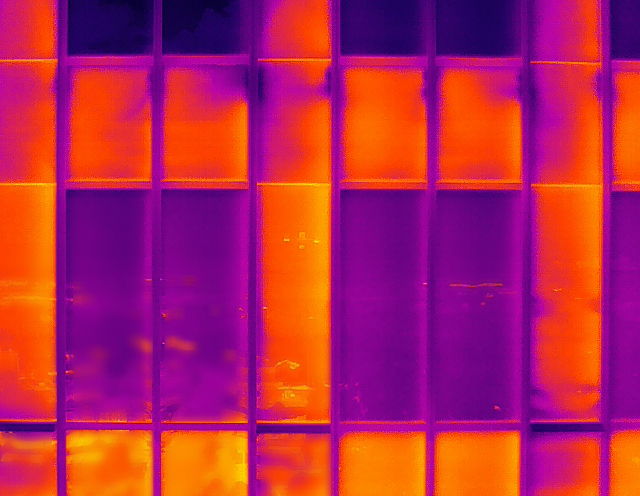

During the design and construction phases, digital twins help architects, engineers and contractors make materials and mechanical configurations more sustainable, while sensors that feed data to AI enable a high degree of monitoring and adjusting of a building’s energy efficiency and emissions during operations.

And as these sensors have become more sophisticated, they have also become less expensive and more accessible. “With that, you are seeing more prevalence with digital twins as they relate to both the building and the job site,” explained Ramtin Motahar, founder & CEO of Joulea, a building energy-efficiency software provider.

The virtual world’s chief engineer

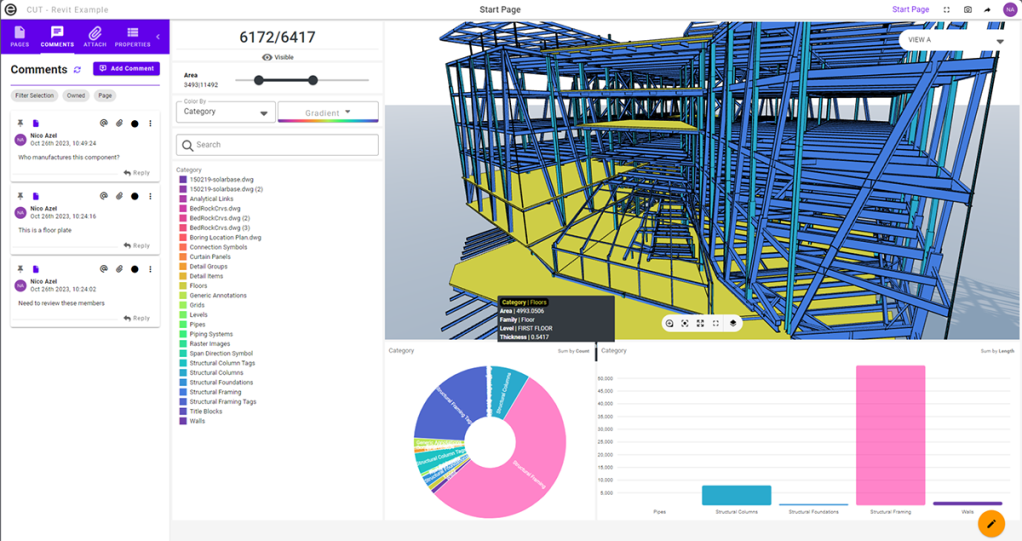

Members of the AEC community are maximizing the powers of digital twins to design and build structures with the lowest possible impact. Engineering firm Thornton Tomasetti, for example, is developing Beacon, a plug-in for Autodesk Revit. The open-source embodied carbon monitoring platform can inform engineers about acute emissions in both their materials and construction processes.

Here, a machine-learning model can predict the carbon emissions of materials based on thousands of potential combinations and use cases, all before a finished product is even agreed upon. “It’s a way of optimizing without doing a full analysis, and then doing a final analysis,” observed Robert Otani, the firm’s chief technology officer.

Digital twins and their associated technologies often evolve concurrently with a building’s development and later with its operations.

“The real help starts in construction, and then develops into post-occupancy,” Motahar noted.

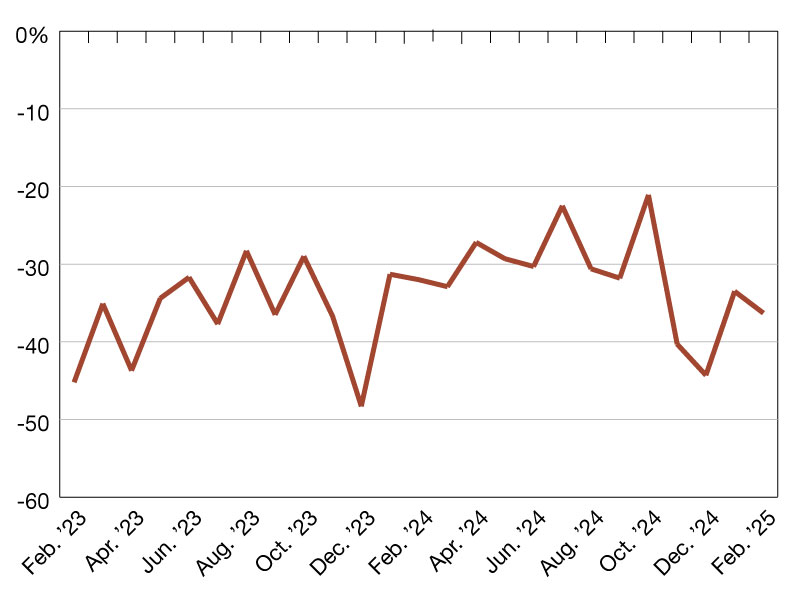

But while the carbon contents of materials cannot be changed once they are in place, emissions savings gained through energy efficiency can continue to improve as the technology improves. So energy efficiency is where digital twins are most prevalent.

Everything from lighting and temperature controls to mechanical systems can be monitored and managed in the virtual realm, with machine learning-based automation often managing the decision-making process.

“It can understand what parts of the building are consuming a lot of electricity for heating and cooling, for powering, for lighting, appliances or other types of internal devices, and it can make judgement calls and decisions off of that,” said Zak Kostura, an associate principal at Arup.

“Some (digital twins) involve changing mechanical systems, and so we have implemented evolutionary algorithms in order to take a particular building and find thousands of ways to make the building operate at a net-zero baseline level.”

Often, these are micro adjustments that a human may not perceive as valuable, but they can influence sustainability at a grand scale.

“If you reduce (a quarter) percent of energy here and there and 5 percent here, and all those little quarter percents add up to huge numbers over the span of, say, a year, it makes the overall impact of the energy reduction and greenhouse reduction opportunities much more significant,” Dauser added.

Growing pains

While it may be tempting to delegate every aspect of performance monitoring to a virtual assistant, developers, engineers and property managers would do well to understand their current limitations, experts say. For starters, any digital twin is only as good as the data it’s founded on.

“If it is pulling from a conventional metering setup, then you really just get one data point,” Kostura explained.

In contrast, digital twin users often need to submeter their buildings, dividing data room by room or service by service, and this may be easier said than done. “Buildings, as they have typically been built, do not inherently collect the data that you need for a complex digital twin,” Kostura reflected.

Still, expectations for what digital twins are capable of are high. For example, if good data hygiene and analysis can exist at the building level, then there’s no reason it cannot help address broader decarbonization goals, Kostura suggested.

“I think that that is where it goes,” he said. “It allows us to scale. We are not talking about a building anymore—we are talking about a city, which is where we need to get to.”

Dauser noted that 80 percent of the buildings that will exist in 2050 already exist today. “You can’t solve these problems just through new construction,” he said.

You must be logged in to post a comment.