Economist’s View: Why the Fed Will Keep Raising Interest Rates

Count me on the “bearish” end of the spectrum when it comes to real estate expectations in 2023.

Count me on the “bearish” end of the spectrum when it comes to real estate expectations in 2023. Of late, there have been murmurings of optimism when it comes to prospects for the Fed to start easing the monetary brakes in the months ahead.

So, the argument goes, inflation has peaked, and the December CPI report marked the sixth consecutive monthly decline in that metric, which fell from a 9.0 percent mark in June 2020 to a 6.4 percent year-on-year change by year-end. While still above the Fed’s target of 2 percent, the direction of prices has been altered by monetary policy since last March. The deceleration of the pace of increase in the Fed Funds rate from 75 basis points to 50 bps in December has been taken as a signal that the central bank is moving to a more accommodative stance.

READ ALSO: Interest Rate Hike #8: The Impact on CRE

At this writing (mid-January 2023), the target range for Fed Funds is 4.25-4.50 percent. Despite recent retreats in retail gas and used vehicle prices, many key items were still rising at double-digit rates as of December. These include food-at-home, fuel oil, electric and gas utilities, and transportation services (especially airfares). The Fed is not likely to declare victory quite yet; nor should it.

Between January and June, there will be four meetings of the Federal Open Markets Committee, the usual moments for reviewing interest rate policy. (By the time this essay is published, one of those meetings will have already occurred.) My expectation is that the Fed will set the upper end of the Fed Funds rate at a minimum of 5.5 percent, and possibly at 5.75 percent by June. That would involve at least one further 50 bps increase, followed by two or three 25 basis point nudges. (During the Jan. 31/Feb. 1 meeting of the FOMC, the Fed increased the Fed Funds rate 25 bps, putting the range at 4.5 to 4.75 percent.)

Why?

I take Chairman Jerome Powell and his team at its word that they will keep at their inflation reduction effort “until the job is done.” We face inflation headwinds that are likely to be persistent through mid-year. At least three factors influence this outlook: labor markets, continued warfare in Ukraine, and China’s reversal of its zero-COVID policy.

The labor squeeze is unabated in early 2023. Unemployment stands at 3.5 percent, and net new job increases have been running over 200,000 per month throughout the second half of 2022. Job openings have been exceeding the rate of hiring by 73 percent, according to the most recent JOLTS report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. We have long anticipated labor market tightening due to the excess of Boomer generation retirements over new labor force entrants from Gen Z. Beyond this, we have a shortfall stemming from a broken immigration policy. And Chairman Powell has grimly noted that about 400,000 Americans who would have been expected to be in the labor force at this point were permanently lost to COVID-19 deaths. All such elements serve to push labor costs higher, ratcheting up inflation pressure.

On Another Front

Meanwhile, the tragic war in Ukraine grinds on, with terrible human toll on the ground. Beyond Ukraine’s borders, we are now acutely aware of the disastrous impact on world food supplies, energy disruptions cascading in and beyond Europe, and an escalation in spending on the part of Western nations to support Ukraine’s defense. The latter is, in many ways, a fiscal expansion at cross-purposes to central banks’ attempts limit monetary growth. Nearing the anniversary date of Russia’s invasion, hostilities show no signs of ending, meaning global inflation will be entrenched for the foreseeable future.

China’s sudden pivot from a “zero-COVID” policy, which had virtually locked-down the world’s most populous country, has further roiled the global public health crisis. While many perceive the U.S. to be in a “post-COVID” era, nothing could be further from the truth. We are in a “late-COVID” period in which the public—and public officials—are tired of coping with the pandemic. But we are vulnerable to renewed surges of the disease if infection ripples out of China—as it most certainly will. Only 16 percent of the U.S. population has taken the bivalent vaccine made available last fall, and we still have an average of 500 daily deaths from COVID-19 as of early January. On the inflation front, we cannot be confident that trouble in the supply chain is behind us, and the economy has risk in that regard. The Fed will not be sanguine about supply chain inflation risk under such conditions.

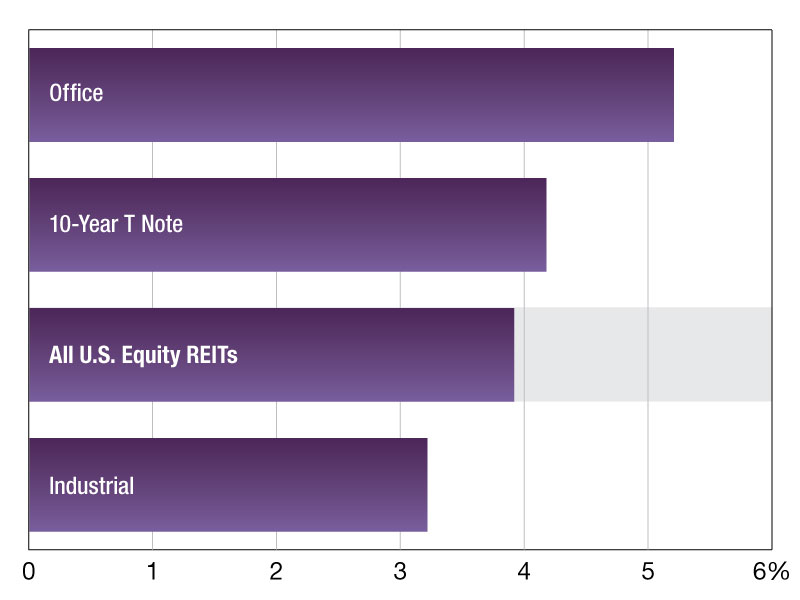

Real estate investors, confronting probable upward movement in interest rates, will be repricing commercial property assets with higher going-in capitalization rates. That is necessary, as rising risk-free rates are pushing spreads to zero and even into negative territory for the most popular property types: apartments and industrials. Beyond that, investment analysis will need to reconsider the risk premium needed for IRR evaluation and the prospect for future inflation in setting reversionary cap rates now that such risks are more top-of-mind.

The generation-long experience of disinflation—and the aggressive monetary policy that has been needed to cope with both the Global Financial Crisis and COVID-19—is now being eclipsed by an investment environment where zero-bound Fed rates can no longer be assumed to recur. When the Fed begins to ease (as it will, probably within the year), I expect real estate yields to more resemble pre-2005 levels than the averages of the post-GFC era. Recession or no recession in 2023, commercial property pricing faces a downturn that could be significant.

You must be logged in to post a comment.