Federal Energy Bills Propose Revamped Policies

Landmark legislation that could influence energy practices nationwide faces challenges as it makes its way through Congress.

Image of U.S. Capitol courtesy of Ian Lee via Flickr

One of the most far-reaching pieces of federal energy legislation in recent memory is making its way through Congress with an uncertain future. Introduced in late February, the bipartisan American Energy Innovation Act aims to modernize the U.S.’ energy policies through a wide range of measures.

Among them are efficiency strategies, renewable energy, storage, carbon capture, advanced nuclear power, industrial and vehicle technologies, cyber and grid security, and workforce development.

Senator Lisa Murkowski

At the moment, the legislation proposed by Senators Lisa Murkowski, Republican of Alaska, and Joe Manchin, a West Virginia Democrat, remains in limbo, as the result of a dispute over an amendment dealing with hydrofluorocarbons. What’s next is as yet unclear.

Introduced by Louisiana Sens. John Kennedy, R-Louisiana, and Tom Carper, D-Delaware, just as the package was set for a vote, the amendment would phase out the use of HFCs, which are commonly used in air conditioners and refrigeration and known as “super-pollutants” for their heat-trapping power.

“Everybody thought this thing was pretty much packaged up and ready to go,” said Alex Ford, director of federal affairs for NAIOP. The amendment has powerful backing, “so it was surprising that that was blocked.”

Code Words

Assuming the Senate can knock the HFC curveball out of the park, the next issue will be an amendment dealing with two code-related sections in the Energy Savings and Industrial Competitiveness Act of 2019 sponsored by Senators Rob Portman of Ohio and Jeanne Shaheen of New Hampshire.

“There’s a little back and forth with the actual language there in terms of the payback period,” said Ford, “so even if the HFCs get sorted out, we’ve got a new round of negotiations that’ll probably have to happen.”

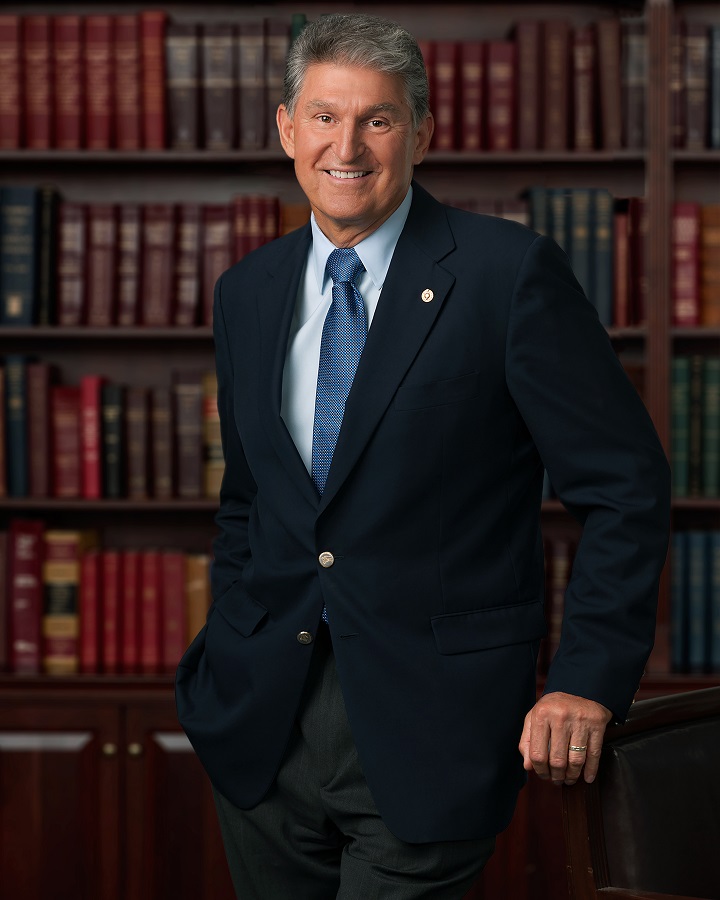

Senator Joe Manchin

The building code provision also is the central focus of BOMA International’s advocacy in the massive energy bill, reported John Bryant, the organization’s vice president of advocacy and building codes. If enacted, the provisions would not have an immediate impact. Instead, they would change the way efficiencies are built into building codes, which would then affect states and counties around the country as they adopt building codes.

“In essence, it’s really more of a process bill and it kind of mirrors and pushes efficiencies and matches them with cost-effectiveness and return on investment,” Bryant explained.

Bryant describes efficiency gains in the last few code cycles as “tremendous,” noting that easier issues have been addressed in previous codes. “Now as we continue to look to write more advanced codes, we really have to figure out, ‘Okay, what are the costs associated with these efficiency gains?’ just to make sure we have the right information on the table before anything is adopted.”

For example, at the federal level, when the Department of Energy sets an efficiency target, it engages in a rule-making process during which stakeholders can comment and cost and return on investment are estimated. That process through which “real-world implications” are laid bare, Bryant maintains, is what is missing from state and local building code efficiency code upgrades.

Similarly, NAIOP has supported the bill since it was first introduced a decade ago. Aquiles Suarez, senior vice president for government affairs for NAIOP, “Everyone wants to be the ‘green’ mayor or the ‘green’ senator,” according to Suarez. While there is a societal desire and a business case to be made for increasing energy efficiency, many mandates have imposed arbitrary goals on the industry over the years, he added.

No Mandate Needed

Aquiles Suarez, NAIOP Photo by Dennis Brack

In contrast, the Portman-Shaheen provisions are to encourage states to pursue building codes that increase energy efficiency without a mandate. Further, in determining these model building codes “you have to take into account the magic phrase ‘economic feasibility’ of achieving the targets and you have to include an ROI analysis,” Suarez said.

Commercial real estate industry advocates fear that the unusually large energy package, will get lost amid more pressing issues like the sudden and seismic shift in the global economy caused by the coronavirus.

Meantime, the Clean Futures Act introduced in the House in early January has met roadblocks of its own. The flagship climate bill House Democrats have been promoting details decarbonization strategies for each sector of the economy as well as new concepts for achieving nationwide net-zero greenhouse gas pollution.

This bill similarly spotlights the building sector along with the transportation sector, the power sector, and the industrial sector. The draft language says it “aims to improve the efficiency of new and existing buildings, as well as the equipment and appliances that operate within them” and also that it would establish “national energy savings targets for continued improvement of model building energy codes, leading to a requirement of zero-energy-ready buildings by 2030.”

In contrast to the Senate’s energy package, the House legislation is being criticized by climate activists for not being aggressive enough in its policies tackling greenhouse gas emissions.

You must be logged in to post a comment.