Has the Pandemic Changed NYC’s Public Realm Forever?

The pandemic has put the spotlight on public space, leading to dramatic transformations of New York City's urban fabric.

The global health crisis has transformed not only the way people live and work, but also the manner and place they interact. Due to new health and safety standards, much of the social contact that usually took place indoors has reemerged outside: in the streets, public parks and plazas. While some of these changes may only be temporary, could COVID-19 leave a permanent mark on the city’s urban fabric?

Mike Aziz, partner & director of urban design with New York-based architecture firm Cooper Robertson, thinks that the public space as we know it will undergo several changes going forward. “The design and use of the city’s largest public realm assets—streets—are often rethought in the wake of a crisis or other catalytic series of events. They will be permanently reshaped as a result of the pandemic, too,” Aziz told Commercial Property Executive.

Lessons of the past

Historically, health crises have played a significant role in shaping the urban fabric of human establishments, commanding the rethinking of building codes and zonings, and reaching broader structures on administrative and governmental levels.

New York City in 1930. Image by Lewis Hines via Wikimedia Commons. This media is available in the holdings of the National Archives and Records Administration

At the beginning of the 20th century, as NYC’s buildings grew taller and were positioned closer together, concerns regarding the deficit of natural light and air also increased, hence the birth of the city’s first zoning resolution in 1916.

One of the most important motivational factors behind creating such a vast green space as Central Park was also public health-related. After 9/11, bollards within the Financial District and Times Square have become permanent fixtures and design elements, altering streetscapes indefinitely.

Through AIA New York, Aziz is currently working on the Post-COVID-19 Cities initiative that recognizes the current opportunity to advance equitable and sustainable urban strategies and that is loosely modeled on the New York/New Visions efforts from the post-9/11 period.

“The traditional sense of New York City as a place of closeness, proximity and intimacy was challenged by COVID-19, creating a new relationship between city dwellers and the city itself,” David Vega-Barachowitz, director of urban design at WXY, told CPE. Post-pandemic anxiety and social hesitancy will most probably linger on even after restrictions are fully lifted. Following more than a year of constraints and sequential lockdowns, entities on all levels are trying to get the ball rolling again, in a joint effort to repopulate the city.

Change is happening

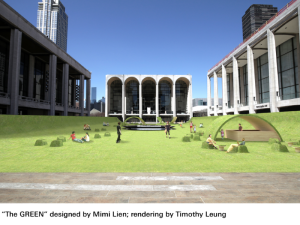

Traditionally considered “grey” spaces have been granted a new, fresh look. Lincoln Center’s Josie Robertson Plaza has just been transformed into a luscious synthetic public lawn, designed by Mimi Lien. “The Green” is part of Lincoln Center’s initiative to kickstart the revitalization of the arts sector. Covering 14,000 square feet, the art installation will be available to New Yorkers through September.

Stone-paved Josie Robertson Plaza offered no seating before it was transformed in The Green, a recyclable, biobased SYNLawn oasis. The entire space is now a large seating area, available to New Yorkers since May 10.

Little Island, a new 2.7-acre park in Manhattan’s southwest riverside, combines the public park experience with world-class performance space. A collaboration between Hudson River Park Trust and the Diller-von Furstenberg Foundation, the Heatherwick Studio-designed project includes an outdoor theater for 700 people and a performance space with a capacity of 200 people. The pier groups together organically shaped concrete piles that emerge from the water, on top of which an undulating landscape is created, with pathways and viewing platforms.

“We have seen more parkgoers out in our parks during the pandemic. It is a good sign as we know how much New Yorkers have relied on our parks over the past year,” Dan Kastanis, press officer at the NYC Department of Parks & Recreation told CPE.

In April, the department began construction on 50 Kent in Brooklyn’s Williamsburg neighborhood. Once home to a manufactured gas plant, the $7 million project will reshape the 1.9-acre site between North 11th and 12th streets into a new public park, with lawns, water play areas and forest groves. “The project’s groundbreaking reflects and advances the City’s mission to build a more equitable 21st century parks system,” Kastanis added.

Greenery and biophilic design have gained popularity in both the private and public sectors. With office leasing in Manhattan at historic lows, landlords are integrating a variety of incentives to lure tenants back into their towers and outdoor space has been a crucial one.

“In addition to the many COVID-19 safety protocols owners across the city have implemented in their office buildings, many are focusing on how they can incorporate the outdoors into their offerings,” said Erik Horvat, managing director and head of real estate at Olayan America.

RXR Realty and Olayan are in the process of reimagining 550 Madison, an iconic office tower designed by Philip Johnson and John Burgee that became New York City’s youngest landmark in 2018. The property includes a half-acre privately owned public space (POPS) that will receive a Snøhetta-designed makeover. “It’s more important than ever to provide amenities that promote wellness and healthy living,” according to Horvat.

Expected to be completed in 2022, the privately owned public space attached to the 550 Madison tower will be twice its former size and will include an artisan food kiosk, open seating, water feature and public restrooms. Rendering courtesy of Snøhetta, MOARE

550 Madison Garden will be the largest green space in the Plaza District and will feature plants that thrive regardless of the season—in anticipation of year-round use—covering 40 percent of the building’s outdoor space. The property will capture enough rainwater to fully irrigate its garden.

In a dense urban core like Manhattan, POPS are an important part of the city’s urban fabric, especially in commercial districts where open space is limited. Owned and maintained by private property owners in exchange for bonus floor area, the program dates back to 1961, when New York City’s Zoning Resolution was last overhauled.

Last summer, Mayor Bill de Blasio temporarily suspended certain zoning regulations for the nearly 600 New York City POPS attached to more than 380 buildings, setting up a blank stage for new dining and retail amenities.

“What the executive order may ultimately lead to is a new trend in which future POPS will need to have a more extensive array of public services and programs,” Aziz noted.

New possibilities

Established last June, the New York City Department of Transportation’s Open Restaurant Program is part of the city’s recovery agenda, allowing restaurants to expand outdoor seating. “The program has opened many New Yorkers to the possibility that curbsides can serve multiple, economically generative functions beyond street parking. … The value of these spaces will continue to rise in the post-pandemic era,” Vega-Barachowitz believes.

Zuccotti Park, a Cooper Robertson-designed POPS in Lower Manhattan. Image courtesy of Cooper Robertson

Community-based organizations, BIDs or groups of three or more restaurants on a single block now have the option to fully close streets, an extraordinary phenomenon in New York. There has been precedent for DOT allowing short-term weekend closures for events—such as Summer Streets—but the COVID-19 crisis has impacted street closures in a completely new way. The pandemic was the first time that the DOT regularly closed large swaths of street space to traffic, realizing the value of street space as public space across all five boroughs, according to Vega-Barachowitz.

Starting out as an ad-hoc response to the pandemic, the initiative failed to meet expectations in its first stages, but as time passed, it became formalized and better designed. “The program helped generate a greater public understanding of the reality that you can’t just plop down some cones on a street corner and call it a day. This is where city government has an obligation to step in and create the kinds of standards and guidelines that will help ensure programs like Open Streets engage with communities and meet a high-design standard,” said Aziz.

Regulations needed

While some streets may eventually become permanently car-free, more nuanced and flexible regulations are likely to emerge, such as after-school play streets and weekend closures. With outdoors lowering the risk of virus transmission, demand for street space is high, with a variety of institutions already interested in utilizing the newly accessible resource for cultural events and performances. According to Vega-Barachowitz, WXY has been working with multiple BIDs and neighborhoods on proposals to pedestrianize parts of their street networks after the COVID-19 crisis wanes.

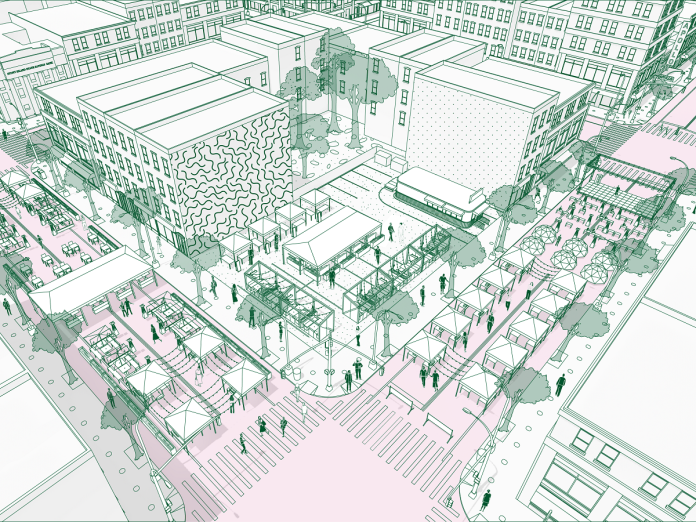

The Downtown Brooklyn Public Realm Action Plan aims to improve the pedestrian experience of downtown Brooklyn’s public realm, spanning 370 acres from Columbus Park to the Barclay’s Center. Rendering courtesy of BIG, WXY

In addition, over the past year, the pandemic-induced bicycle boom has highlighted the need for a better bike lane network. In 2020, the DOT constructed a record 28.6 miles of new protected bike lanes across all five boroughs—the largest one-year expansion of protected bike lane construction in the city’s history—and an additional 35.2 miles of conventional lanes. Moreover, two of the Brooklyn Bridge’s car lanes are also going to be handed over for cyclist use.

COVID-19 has put the spotlight on public space quality and New York City’s streetscape is undergoing one of the most dramatic transformations in modern history. “Pre-pandemic, who could have imagined that the city would give up street parking spaces to restaurants?” Aziz wondered. And as the city gradually reopens, time will tell how the enhanced pedestrian experience will continue to evolve.

You must be logged in to post a comment.