How CRE Liquidity Reigns Despite Volatility

Debt and equity sources amassed abundant dry powder last year, but caveats linger.

A rebound in investment sales in the fourth quarter of 2020 not only helped salve the bruising second and third quarters but also served notice that investors remained bullish heading into 2021. For the right asset, equity and debt providers have plentiful funds to fill every niche of the capital stack.

“There was a ton of capital sitting on the sidelines in 2020 and even more capital was raised,” said Rowan Sbaiti, senior managing director of acquisitions for BH Properties, a real estate investment firm based in Los Angeles. “Today the market is awash with capital because it didn’t get deployed last year.”

READ ALSO: CRE Finance Outlook Brightens

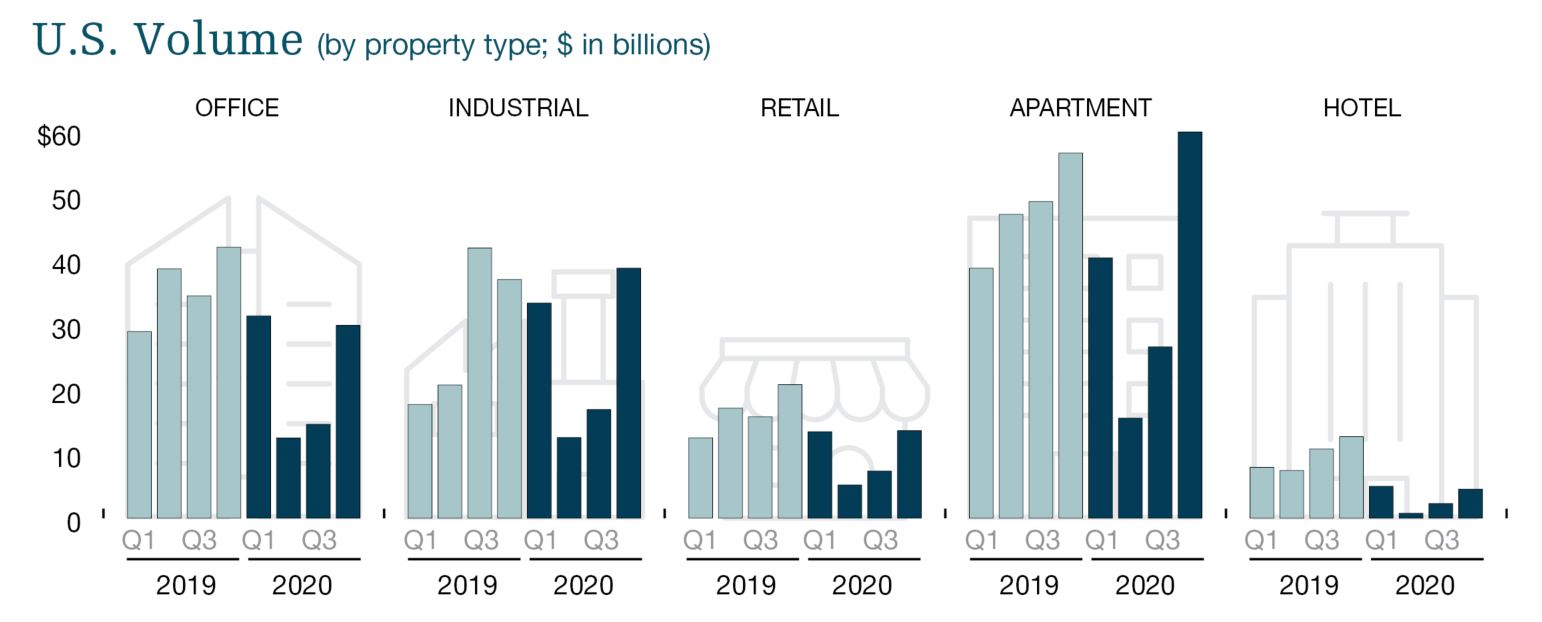

Commercial real estate sales volume dropped 32 percent to $405.4 billion in 2020 from the prior year, according to Real Capital Analytics, which tracks deals of $2.5 million and above. But property sales in last year’s fourth quarter represented a year-over-year decline of only 19 percent, a vast improvement over the second and third quarters, when year-over-year dollar volume plunged more than 60 percent and 50 percent, respectively.

The multifamily, industrial and office categories accounted for the bulk of sales, and observers expect debt and equity providers to continue concentrating on these sectors until COVID-19 comes under control or owners and special servicers begin to bring distressed hospitality and retail assets to the market.

Lowering leverage

Yet even within the favored property types, capital providers have become more cautious and are emphasizing quality, fundamentals and credit profiles of individual assets and markets. While office sales were relatively brisk last year, for example, the assets have been more of a challenge to finance, said Chip Sykes, managing director for capital markets at JLL in Atlanta. Apartment projects in overbuilt and concession-heavy markets are also harder to finance, said Michael Snodgrass, executive managing director of the structured finance group for Transwestern in Houston.

READ ALSO: Where Office Sales Volume Shot Up Last Year

In some cases, lenders have pulled back on the amount of senior debt they are willing to loan in general—if they offered 60 percent to 65 percent of value or cost in the past, now they’re offering only 55 percent or 60 percent, observers say. In turn, that is fueling demand for mezzanine debt and preferred equity, which may increase leverage to north of 85 percent.

“In general, borrowers are seeking more leverage in this market if they aren’t able to get the kind of leverage from lenders that they did pre-COVID-19,” said Vicky Schiff, founder & managing partner in the West Coast office of Mosaic Real Estate Investors, a debt fund. “They need to fill out their capital stack and prefer to do it with mezz or preferred equity because it’s cheaper than equity.”

While Mosaic Real Estate focuses primarily on construction loans, it has also provided preferred equity to about 25 apartment assets in which borrowers are typically undertaking light value-add projects, she said.

Late last year, KKR acquired a 9.7 million-square-foot industrial portfolio across multiple states from High Street Logistics Properties for $835 million. It tapped Barclays for a $740 million commercial mortgage-backed securities loan, which included about $80 million in mezzanine debt that was purchased by Oxford Capital Group, along with other subordinated bonds.

“Lenders are flush with money, and unless you own a hotel or shopping center that’s not doing very well, you can find debt at extremely favorable prices,” said Thomas Traynor, vice chairman in debt and structured finance at CBRE, which arranged KKR’s financing. “Interest rates are going up but they’re still at historical lows, and LIBOR (the London Interbank Offered Rate) is close to zero.”

Stretch senior preference

As with financing in general, the price of mezzanine debt and preferred equity rose in the earliest of COVID-19 days, pushing up the blended cost of senior and subordinate debt to around 12 percent, Snodgrass said. Since then, however, mezzanine interest rates and preferred equity returns have bounced back to the pre-pandemic range of low to mid-teens, taking the blended rate back to 8 percent or 9 percent.

Debt funds have returned, too. Many were forced to the sidelines early in the health crisis as credit line sources dried up and the collateralized loan obligation market stalled. The funds have resumed providing so-called “stretch senior” construction loans, as well. The loans combine a less expensive first lien mortgage with more expensive second lien financing and typically topping out at 80 percent of cost, Snodgrass added. Often debt funds then bifurcate the loan and sell the first lien note to a bank.

READ ALSO: Vaccine to Trigger Q3 CRE Recovery

“Many borrowers prefer a stretch senior loan because it’s cheaper and more streamlined than going the traditional route of a senior lender and a separate mezzanine lender,” Snodgrass said. “It’s going to cut down on legal costs—you have one set of loan documents, and you have only one set of lender lawyers to deal with.”

Equity’s growing risk aversion

Like lenders, equity investors have become more cautious. Many are looking for more favorable waterfall structures, which determine how cash flow is divvied between the equity provider and the sponsor, said Scott Modelski, managing director with Black Bear Capital Partners, a New York-based boutique firm specializing in structured debt and equity advisory.

After initial return hurdles are met, he said, it is not unusual today for the split to max out at 60 percent for the equity investors and 40 percent for the sponsors. Prior to the pandemic, typical splits maxed out at 50/50.

Joint venture equity providers also pivoted toward providing more mezzanine or preferred equity to obtain a security position in a property’s capital stack to reduce their risk, said Modelski and Matthew Stearns, a senior managing director with Black Bear Capital.

Some equity investors prefer Southeast and Southwest markets to the Midwest, and, more broadly, are shying from cities that are losing residents after implementing strict lockdowns, Stearns suggested. Plus, eviction moratoriums are making value-add deals less appealing in general when compared with financing a new development that will not open for at least 18 months.

“We typically take a deal to around 100 equity groups, and in a normal market, we would have had 20 term sheets by now,” Stearns mentioned. “We’ll eventually land an equity partner, but it’s taking a lot more work and effort than I thought it would.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.