How High Can Long-Term Interest Rates Rise?

Real estate borrowing rates are still relatively low, but the 2017 tax reform package and 2018 trade issues have led to economic volatility and long-term concern.

By Chris Nebenzahl

Chris Nebenzahl

Talk of an inverted yield curve has captured the minds and conversations of economists, stock traders, and real estate investors for much of the past month as economic indicators appear to be softening at year-end. In fact, a section of the yield curve between three-year Treasury bonds and five-year Treasury bonds briefly inverted in early December. But why are short-term rates increasing faster than long-term rates? Or in other words, if the Fed continues to push its Fed Funds target rate, how much higher can long-term rates rise before the entire yield curve inverts?

The answer lies somewhat in the nature of the driving forces behind both ends of the yield curve. Short- term rates, specifically the Fed Funds rate, fluctuate based on the monetary policy of the Fed. Since the Fed sets monetary policy based off of its dual mandate of price stability and a strong labor market, current economic conditions continue to demonstrate a healthy economy and promote additional rate hikes. Inflation remains in the 2.0–2.5 percent range on an annual basis, and the national unemployment rate sits near a 50-year low of 3.7 percent.

The 10-year Treasury rate, however, is a reflection of longer-term views of market sentiment, inflation and global economic output. While 2018 has been a prosperous year from both an economic and real estate front, short- and long-term sentiment have diverged as the year has gone on, and much of the divergence has been caused by federal policy. Both the 2017 tax reform package and 2018 trade issues have led to economic volatility and long term concern.

Sentiments Diverge

Tax reform provided a late cycle boost to many industries, especially commercial real estate, but the stimulus provided in 2018 and 2019 will likely lead to future economic challenges as our national debt increases, especially in the mid 2020s. The recent trade war with China has also led economists and traders to revise their global growth prospects for 2019 and beyond. As the cost of imports increases, combined with the already rising cost of labor, both producer-based and consumer-based industries are likely to slow.

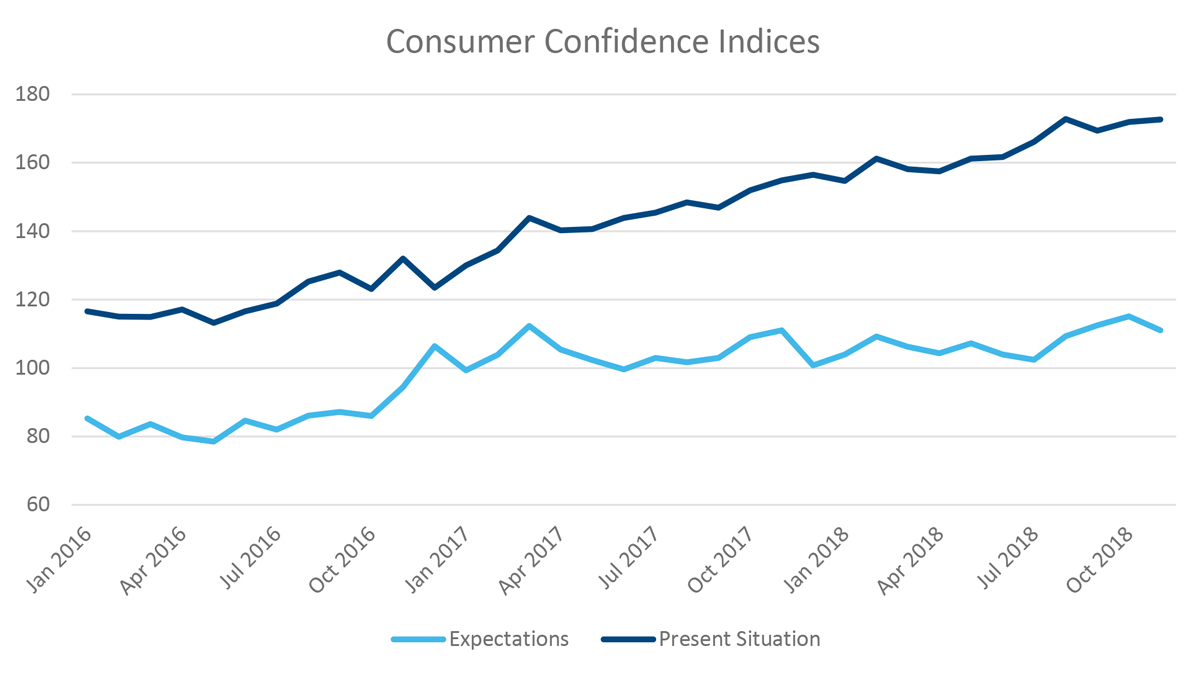

Source: Conference Board, Moody’s Analytics

A clear example of short- and long-term sentiment divergence can be seen within the Consumer Confidence Indices. As of November, the Present Situation index was 172.7, while the Expectations Index was only 111.0. Not only are consumers significantly more confident in the current economy than the future, but the spread between the two indices has doubled from 31.3 in January, 2016 to 61.7 in November, 2018

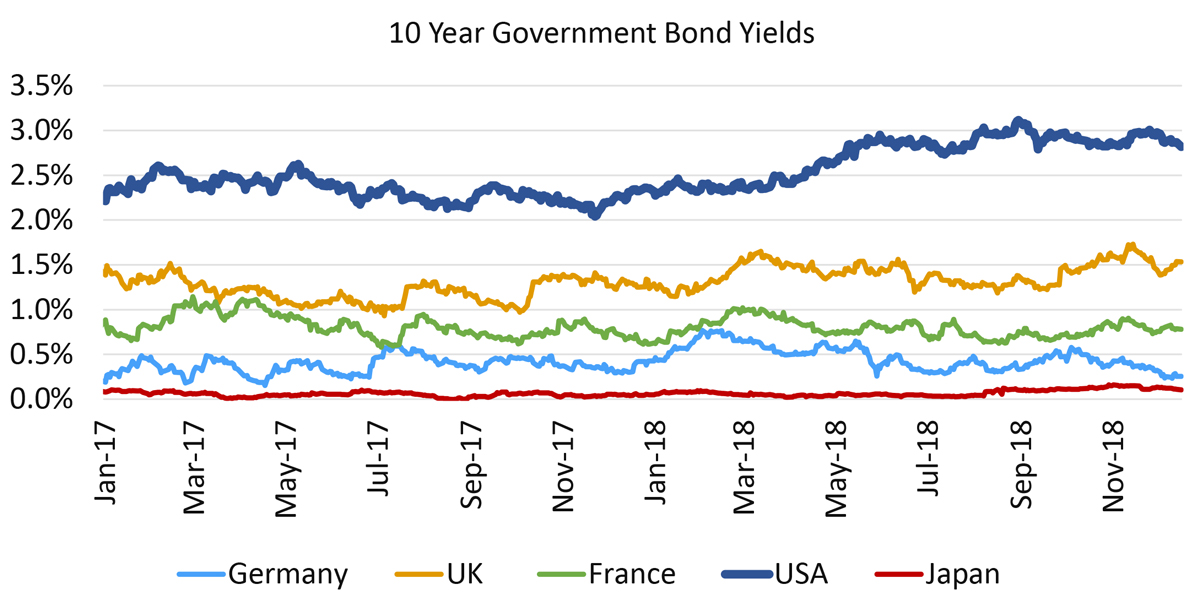

Finally, U.S. Treasuries remain increasingly attractive to foreign investors looking for secure investments. Yields on 10-year government securities across Europe and Japan remain between zero and one percent, and the spread between U.S. bonds and those of other developed nations, is widening. With ample capital available, foreign investment in U.S. treasuries has helped put an upper limit on long term rates.

Source: Investing.com

So what does it mean for commercial real estate borrowers and the outlook for the U.S. economy? By historical standards, borrowing costs remain low, despite the 100 basis point increase in the 10-year over the past two years. Due to continued pressure on the long end of the yield curve, 10-year yields will likely stay within a range of 2.75–3.5 percent, which should not have a devastating impact on commercial real estate borrowing.

However, if the Fed continues its monetary tightening, and the Trump administration pushes forward with additional trade restrictions, long-term economic uncertainty will likely cause the yield curve to invert ―which has historically signaled an oncoming recession.

Chris Nebenzahl is Institutional Research Manager with Yardi Matrix

You must be logged in to post a comment.