How Logistics Developers Can Surmount Inventory Hurdles

Should you build from the ground up or retrofit an older facility? Each option has its upsides.

If it’s one thing that industrial tenants can’t seem to get enough of, it’s logistics-focused industrial space. Despite indications of slowing growth, several key fundamentals are still positive. Rents grew 7.3 percent year-over-year, according to CommercialEdge’s latest national industrial report, even with an uptick in vacancy rates to 5.2 percent driven by more than 1 billion square feet of new supply.

Still, this two-year supply high is expected to decline, as interest rates, construction costs and regulatory roadblocks are likely to further hamper development plans. The CommercialEdge report found that new starts are starting to dry up, resulting in a one-third decline in new inventory over the next two years.

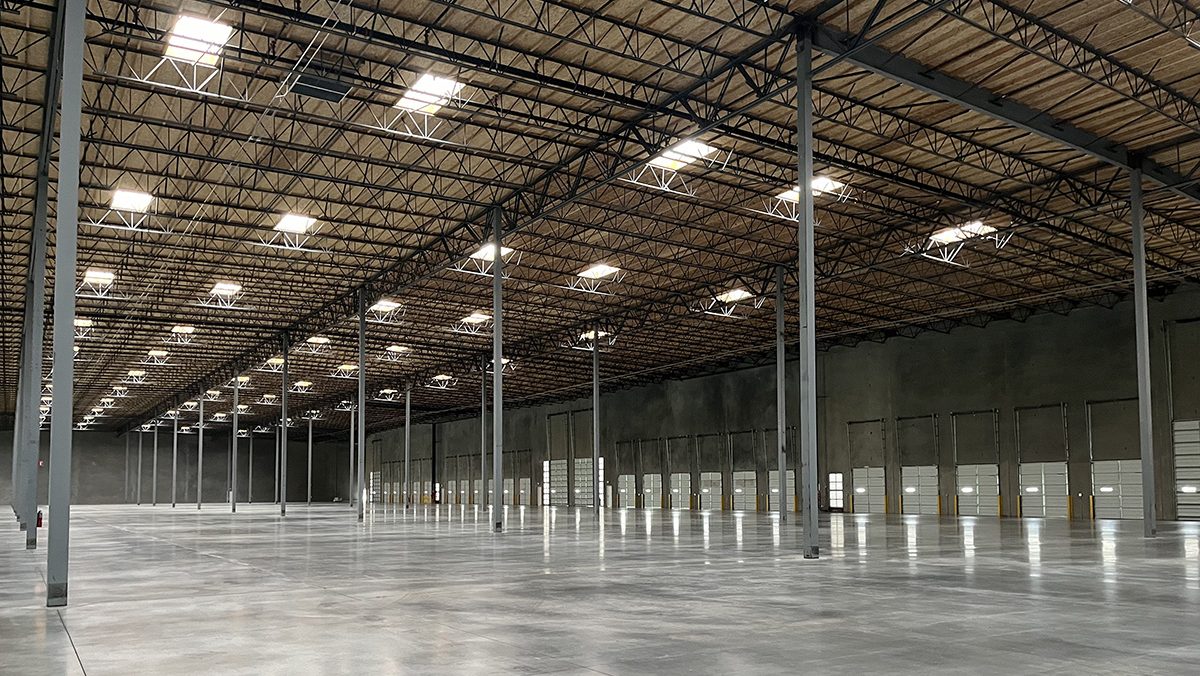

But what does this look like on the ground? Economic hurdles are only part of the challenge. What’s equally difficult is providing the qualities needed to replace a national inventory that averages 44 years old, according to CBRE.

Enter logistics 2.0

Where the demand for new product stock often crops up is in such features as automated packing systems and highway access. Mary Lang, head of Americas direct logistics strategies at CBRE Investment Management, refers to this new generation of supply as “logistics 2.0.”

These facilities are centered on coastal shipping hubs and high-growth population centers, where developers are “trying to aggregate around (metros) that have the highest number of consumers,” according to Lang. In those markets, it may be difficult to fulfill tenants’ needs due to aging stock and prohibitive capital costs.

Charlie Meyer, president of Lovett Industrial, has observed this trend around the growing eastern, western and southern markets where his firm operates. “When you think about where that supply has to go, it’s more around the periphery of cities, so most of the traditional submarkets have been completely built out,” he noted.

But which tenants seek to occupy these facilities? According Tom Simmons, a vice president at Majestic Realty Co., many are third-party logistics providers which may be tenants for relatively short stints, and whose goods “are packed and sorted once they come in. They’re coming in faster than it would typically be for the users of old.”

With this need for speed in mind, particularly as annual e-commerce sales are projected to reach $656 billion by 2029—a 54 percent increase from 2024—the technology inside and around logistics space is equally important.

“We are seeing a lot more automation, robots and AI being deployed within the warehouse, and this actually changes the specifications for construction,” Lang observed. She sees the future as characterized by “automated racking systems that increase the density of storage within the warehouses, or deploying solar arrays on the roof in order to power EV truck fleets,” at a time when electric truck deployments more than tripled from 2022 to 2023.

Construction hurdles

These issues further complicate development, on top of the long-running capital markets crunch. “Landowners of the past 15 years don’t need to sell, transactions will be down dramatically, and leasing activity may not meet the (needs) of the actual building,” said Edward Easton, chairman of The Easton Group. The firm has several industrial developments underway around Florida’s Broward and Miami-Dade counties, where the cost of living is high and average land costs are the highest in the state.

Supply-demand pressure is a factor, as well. A recent analysis found that construction costs are expected to jump between 2 and 4 percent this year. Todd Zabelle, founder of the Project Production Institute and the author of the recently published Built to Fail: Why Construction Projects Take So Long, Cost Too Much, and How to Fix It, calls these struggles the “perfect storm.” A shortage of nearly half a million construction workers is coupled with demand for building materials that often are imported from Asia. “To meet the world’s need for floor plate, you would have to build the equivalent of a Paris every week or a New York every month,” he noted.

As Majestic Realty’s Simmons notes, the cost of building new industrial product has jumped by leaps and bounds in the past several years. As recently as 2019, he recalled, you could get a new facility up and running at around $100 per square foot. But today, “you can find yourself at $150 to $175 to try and reconstruct that same warehouse,” he said.

Even when a suitable parcel can be found, many developers, particularly those operating in regulation-intensive states such as California, have found it difficult to make new development work financially. Such hurdles can hold up project delivery for years.

In Southern California’s key markets, capital costs, zoning restrictions and regulatory hurdles regularly stifle development. A shortage of building inspectors and changing building codes compound these challenges. “10 to 15 years ago, (it) would have taken 12 months to build, and now these projects are taking three years,” said Patrick Schlehuber, chief investment officer at Rexford Industrial.

Diamonds in the rough

Considering these hurdles to ground-up development, retrofitting older properties and adaptive reuse often provide an attractive alternative. Under the right circumstances, these properties can be competitive with new product for a variety of reasons. Though they may not offer all the bells and whistles of new builds, upgraded facilities can meet the needs of a wide variety of tenants, are largely immune to regulatory hurdles and are less likely to stir up NIMBYism than ground-up development.

Anthony Cataldo, chief operating officer at Lowney Architecture, sees opportunity to serve clients who mainly need to meet more basic storage and shipping needs. “Some tenants don’t need new Class A buildings,” he pointed out. “They don’t stack that high, and they turn over a lot of product so they can get by with a lower clear height without as many docks.”

Yet retrofits that are cost-intensive are a mixed bag. The decision to jump in turns on whether rents justify the cost to build. That’s the case in many high-growth markets.

“You used to see this only in a couple of small pockets in infill areas like Los Angeles and northern New Jersey, but now you are starting to see rents justify redevelopment in even more markets,” reported Meyer of Lovett Industrial. Lovett’s current pipeline includes Addison Innovation Center, an adaptive reuse project taking shape in the northern Dallas suburb of Addison, Texas. The company is converting a 28-year-old call center into a 140,698-square-foot office-warehouse facility and will add a new 101,364-square-foot warehouse.

The project was attractive not only because of the high rents that Dallas industrial properties command, but because of the site. “The parking lot is large enough to add another building within, and we are now in the process of renovating the existing building, turning it into a dock-high warehouse, and building a new building in the parking lot behind the existing building,” Meyer said.

Still, the technical challenges of turning diamonds in the rough into logistics 2.0 facilities can’t be overlooked. CBRE’s Lang cites the example of replacing a 5-inch reinforced concrete slab with a 7- or 8-inch slab. It’s possible, but also complicated and costly.

“You have to remove the existing tenant for a building for at least a year, and you have to jackhammer out the entire slab while replacing the floors and the roof, and then figure out how to support the existing column structure so you can pour a new slab,” she said. That’s a reminder that a complex upgrade can be the right choice but requires detailed analysis of the building’s structure and the project’s cost.

You must be logged in to post a comment.