How to Challenge Your Property Tax Assessments

A step-by-step guide from a veteran attorney to navigating the process of disputing real estate valuations by local government.

By Jerome Wallach, Esq.

Jerome Wallach

In most jurisdictions, taxpayers may meet with the assessor or assessor’s representative to deliberate and possibly resolve issues concerning taxable real estate valuation.

First, contact the assessor’s office to request a meeting. Getting past recorded messages may be a challenge in some instances, but talking to a human being is necessary.

During that initial phone call, be prepared to describe the problem and point of the discussion, then ask for a date and time to meet. Be sure to request the meeting in sufficient advance of filing deadlines for any appeal process.

Before the meeting, identify an objective (typically a lower assessment) and a plan to achieve that outcome. Be optimistic, but recognize that the assessor’s office may reject the taxpayer’s position. During the discussion, be reasonably flexible; passion and anger are seldom persuasive and will detract from an otherwise sound argument.

Fix the Facts

There are a number of valid concerns other than overvaluation which, if properly addressed and corrected, can result in significant savings.

The most obvious reason to discuss the property with the assessor is the need to correct a simple mistake on the part of the assessor’s office. Computer-generated assessed values are now widely used and accepted. The resulting values are no better than the data fed into the database, so review assessments with an eye on the broad picture.

Pay particular attention to the address and all measurements, which are common sources of error. Be sure the property hasn’t been confused with some other property of greater value. If the property is improved, review the records available on the assessor’s website to see if the improvements are accurately described and that the land is properly measured. Call any mistake of fact to the assessor’s attention.

Most jurisdictions recognize varying degrees of assessment value depending on property classification. Typical classifications are commercial, residential and agricultural. Each class is assessed at a different percentage of its market value.

Usage is the primary classification determinant. For instance, undeveloped property zoned commercial may be a productive farm, in which case its classification would be agricultural. Point out to the assessor that the property is being farmed and was so used on the tax valuation day. Bring photos and records to establish that farming was the use on value day, and continues to be so.

Make a similar argument in any situation where the assessor classified the property higher than its actual use. Along the lines of classification, some properties are exempt from taxation if used regularly for charitable, religious and educational purposes.

Unless the use is easily recognized and accepted, it is unlikely the assessor’s office will alter its opinion in an informal meeting. The meeting is an effort to convince the assessor that the property is overvalued for tax purposes.

Study the concepts

Unless the taxpayer is a valuation expert, it’s probable he or she is meeting with someone who knows more about property values than the owner does, or at least believes that to be the case. A fundamental understanding of valuation methods is critical to a meaningful dialogue.

Volumes are written on the subject and the law books are full of cases dealing with value concepts. The following provides a thumbnail sketch of these concepts.

The three approaches accepted by all valuation experts are cost, income, and market or sales comparison. Assessors use these approaches daily, and look at property through these lenses.

Cost. If the property was purchased and improved with a new structure or structures within the last five years, the total cost of acquisition and improvement is a good indicator of what the property is worth and how it should be valued for tax purposes.

In the absence of a recent transaction, a credible opinion of the cost to replace the improvements on the property may be useful. There are manuals recognized by value experts that may assist in obtaining and presenting such an opinion as evidence.

Market. If the house next door, built just like the subject home, sold yesterday, then that sale price is a good indicator of the value of the subject house. On its face, the method of seeing what similar properties sell for seems the simplest and most direct way to determine a property’s value.

If only it were so. The more variances there are between the properties, the greater the comparison challenge. Differences can include location, date of sale, condition of the property—the list goes on.

In dealing with the assessor, present listings and recent sales of properties similar to the subject property, if possible.

Income. In short, this is the present value of future benefits, and is the price a knowledgeable person would pay to acquire the future income stream of a given property.

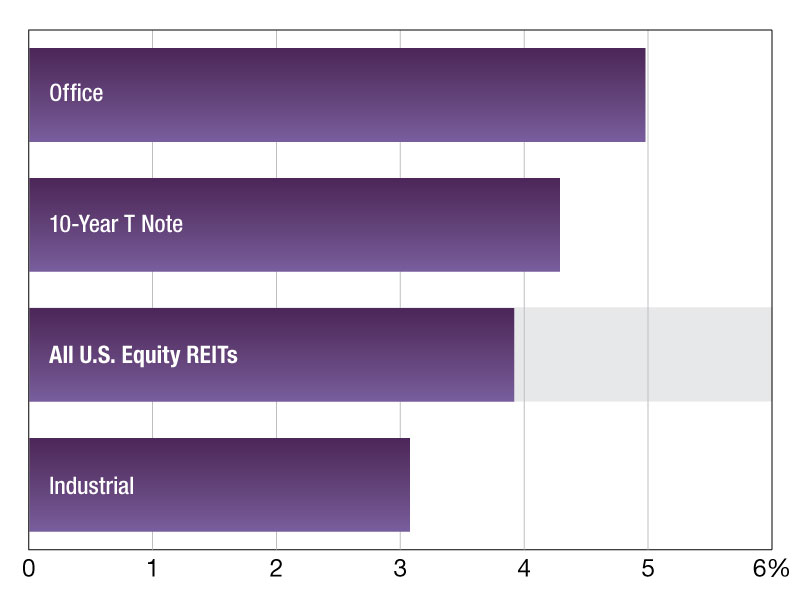

Under this approach, value is typically determined by dividing the net income by the capitalization rate, or the buyer’s initial annual rate of return. The capitalization rate, or cap rate, provides a formula for value calculation, and the higher the cap rate, the lower the value conclusion. The assessor will have a firm opinion of the cap rate and is unlikely to be swayed, but it’s worth a try.

In many instances, arguing the general market cap rate with the assessor is futile. A better approach may be to show why the assessor’s cap rate should be adjusted because of conditions unique to the property. Look for conditions that are beyond the owner’s control and constitute risk to future income.

Arguments challenging the assessor’s cap rate could include the greater risk of lost income due to external factors, such as a highway change or a major demographic shift.

Assessors and their staff consider themselves professionals meriting respect as public servants. To achieve any result from conversing with them, they should be dealt with accordingly.

At the conclusion of the meeting, be sure to document any agreement reached.

Jerome Wallach is a partner at The Wallach Law Firm in St. Louis, the Missouri member of American Property Tax Counsel, the national affiliation of property tax attorneys. He can be reached at jwallach@wallachlawfirm.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.