Is Your Building Ready for Wildfire Fallout?

As pollution hazards increase, operators and managers should step up their focus on indoor air quality.

When wildfire smoke blanketed the Northeast last week, some owners could be confident about the air quality in their buildings. Hines’ 555 Greenwich, a recently completed office and retail building in Manhattan’s Hudson Square submarket, for example, contains a cutting-edge ventilation system that also monitors air quality in real time.

Wildfires are becoming more frequent due to global warming, and wildfire season is getting longer, according to the U.S Environmental Protection Agency. That has stakeholders questioning whether commercial and multifamily buildings have the capacity to properly block the wildfire particulates entering buildings.

READ ALSO: How to Protect CRE From Wildfires

One of the chief ways to make indoor air quality better is to allow as much outdoor air into the building as possible. The dedicated outdoor air system (or “DOAS”) at 555 Greenwich provides 100 percent fresh outside air delivery to the interior spaces at the point of use and 70 percent above code for air delivered directly to occupants, but not before the air meets the building’s sophisticated air filtration system. Needless to say, not every building has such advanced technology.

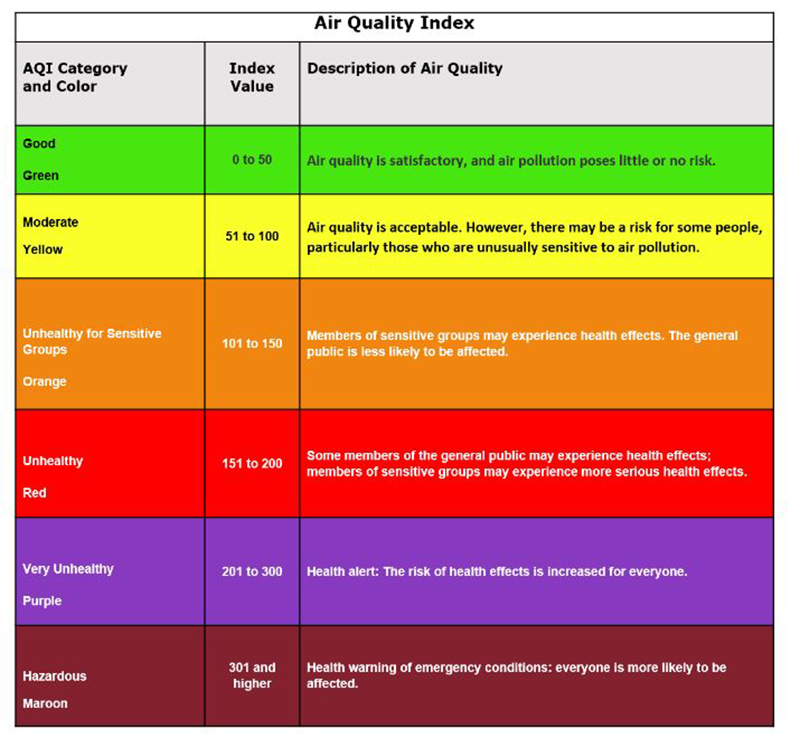

Therefore, the level of hazard owners and tenants faced last week, when the EPA’s Air Quality Index peaked at 484 in New York City and over 400 in Philadelphia, depended on how well the outdoor air was filtered as it entered the building.

Newer and LEED-certified properties—555 Greenwich is Platinum-certified—and upgraded properties will have Merv 13 filters, which can adequately remove the particulates in wildfire smoke, according to Tom Javins, a mechanical engineer based in Missoula, Mont. Javins is currently part of an ASHRAE consensus committee writing a guideline (GPC #44) designed to protect occupants of commercial buildings from wildfire smoke exposure.

READ ALSO: How the Western US Drought Impacts CRE

“If the commercial building has done any work for mitigation of COVID, the particulate size of the virus is about the same as wildfire particulates,” Javins noted, “and they would have made an investment that can carry over to wildfire season.”

There is a key difference, though. The way to prevent against airborne pathogens is to dilute the air with a high ventilation rate. But to block wildfire particulates, owners should limit the outdoor air intake rate to just what is needed for ventilation (ASHRA Standard 62.2), Javins said: “That height during a wildfire will bring in more smoke.”

Unlike hospitals, the majority of commercial properties today do not use those filters, Javins found in research he conducted with the EPA. “Most buildings will very quickly match the outdoor air conditions because they do not have adequate filtration,” he added.

Quality is in the air

Since the pandemic, indoor air quality has been a huge focus for the commercial real estate industry. In March 2022, the Biden administration launched the Clean Air in Buildings Challenge as part of the national COVID-19 Preparedness Plan. And indoor air quality has become a key focus for many owners and groups like ASHRAE and the International Well Building Institute.

For those owners who have not made air quality investments, last week was a “stressful week,” said Matthew Trowbridge, chief medical officer at the International WELL Building Institute, and it highlighted the importance of preparedness and prevention.

“Sometimes the moments that will pay off occur very quickly and without some warning,” he observed. “Sometimes that lasts for a week, like we are experiencing now, and sometimes it lasts for three years, like in the pandemic.”

Trowbridge is hoping the event can be used as a catalyst for owners to think about ways to make a building healthier. Every building and circumstance is different, he said, and “building owners have hundreds of different ways to make buildings healthier, Trowbridge noted.”

During wildfire conditions, IBWI recommends shutting windows; turning off air conditioners at home and using air purifiers indoors; wearing N-95 masks outdoors; and utilizing apps that measure air quality. Vulnerable individuals—the elderly and those with underlying conditions—should limit exposure to the outdoors.

“None of this is rocket science,” Trowbridge said. “It just needs to be done carefully and then combined with other management strategies. I think you can make a huge impact.”

Trowbridge also recommended that owners and managers get involved politically. “The market needs a strong standard to be able to work toward,” he said. “It really is a public health necessity, and there’s also equity issues. We need to make sure that it’s not just the best office buildings. But we need to be working to make sure that safe, indoor environments are available, and for everyone.”

Return to work upside

Questions about indoor air quality last week did not help employers trying to get people back into the office. But, at times like these, commercial buildings may actually be a healthier place to be because many owners have made the necessary upgrades, Trowbridge noted.

“Some businesses are promoting the fact that, once they’ve made these investments in more advanced HVAC systems that enhance ventilation and air filtration systems, they offer a great indoor experience and higher productivity every day,” he said. “But then there are moments like this where the office can actually offer an even more predictably safe experience.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.