Interest-Only Loans May Prove Risky―Eventually

How interest-only loans and other concessions could become weaknesses for commercial real estate when interest rates rise and property values decline.

Market players largely agree that lending standards have not deteriorated despite the sustained economic cycle and positive real estate fundamentals. Bucking the history of past cycles, lenders generally have avoided the temptation to lard properties with high levels of debt while times are good.

Image by Solvod/iStockphoto

That’s not, however, the same thing as saying risk has been eliminated. While it is true that leverage has remained relatively constant in recent years, some measures of aggressive lending have grown as lenders battle to win assignments. One example is the increasing number of loans with interest-only components, which means that fewer loans require borrowers to pay down principal. Also, loan coupons have declined to historical lows as lenders offer tight loan spreads on top of low Treasury yields.

The upshot is that today’s healthy lending environment could be planting the seeds for a problematic refinancing environment when loans mature. Even though loans written today have conservative debt-service and leverage levels, some combination of rising interest rates, higher expenses and weak growth in property income due to a recession could lead to a deteriorating credit environment and eventually produce a sharp uptick in defaults.

Healthy Lending

On the surface, debt market metrics are rosy. The amount of outstanding commercial mortgage debt reached a record $3.6 trillion in the third quarter of 2019, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association. That’s up $75.7 billion from the second quarter and $200 billion year-to-date. The growth comes from all segments of the lender community. CMBS issuance, for example, increased 27.1 percent to $97.8 billion in 2019, while collateralized loan obligations or “CLOs,” which mostly involve short-term lending by debt funds, grew by 38.7 percent to $19.2 billion, according to Commercial Mortgage Alert.

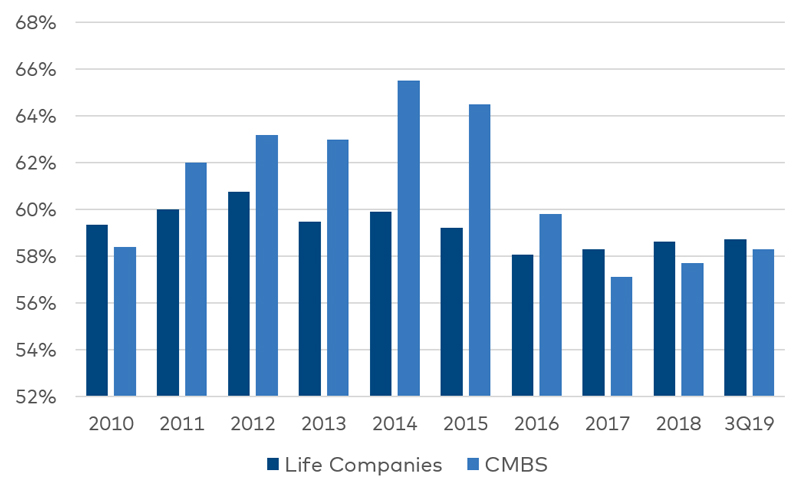

Loan metrics have remained healthy through the cycle. The average loan-to-value ratio of loans originated by life insurers reached 60.0 percent in 3Q19, the highest level in five years, but still nowhere near the typical pre-financial crisis levels of 65–70 percent. The average underwritten CMBS LTV through 3Q19 was 58.3 percent, which was up 60 basis points over 2018 but far below the cycle peak of 65.5 percent in 2014, according to data supplied by Morgan Stanley to the CRE Finance Council, a Washington, D.C. trade group.

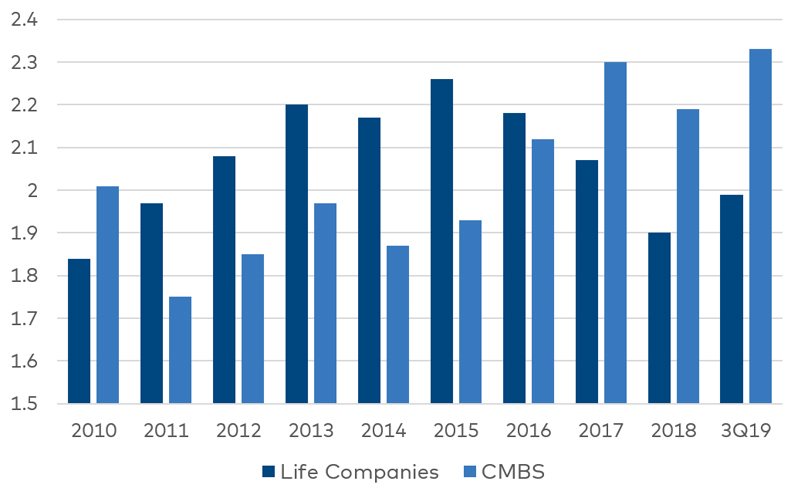

Debt service is also conservative. Life company loans had debt service of 1.99, which means net income of loans was twice as much as loan payments. The average CMBS underwritten debt-service coverage (based on net operating income) through 3Q19 was even better: a cycle high 2.3, according to the CREFC database.

Average Commercial Mortgage Loan-to-Value

Sources: American Council of Life Insurers, Moody’s Analytics, CRE Finance Council and Morgan Stanley

Meanwhile, the default rate of commercial mortgages originated in the current cycle are at historical lows. As of late 2019, delinquency rates were less than 0.10 percent for insurance companies and government-sponsored enterprises Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, less than 0.50 percent for commercial banks and 2.3 percent for CMBS. Delinquency rates have been a miniscule 0.10 percent for life companies and the GSEs since 2013, while the rates for banks and CMBS are the lowest since before the financial crisis and have steadily dropped in recent years.

What Could Go Wrong?

The commercial mortgage industry is blessed with almost optimal conditions. Demand is boosted by a plethora of equity sources chasing deals that keeps transaction volume high. Low interest rates have increased demand for refinancing from borrowers that want to lock in long-term debt at low rates. The performance and inherent conservative nature of commercial mortgages, combined with low yields for other bond products, has created an inflow of capital from investors. And although there have been some weak niches, such as secondary market malls, commercial property fundamentals generally have been strong for nearly a decade.

It would be a mistake, however, to believe nothing can go wrong. For one thing, some of the sterling metrics reflect bullish market conditions that can change. LTVs are based on property values, income and acquisition yields. Property values have―on average―more than doubled since the last peak in 2007. Property income has grown consistently throughout the current cycle that began a decade ago, but at some time over the next five to 10 years, the U.S. economy likely will have a recession leading to negative or slower income growth.

Average Debt-Service Coverage

Sources: American Council of Life Insurers, Moody’s Analytics, CRE Finance Council and Morgan Stanley

The same is true of low property yields, which have been hovering at historical lows since 2016. Acquisition yields, or cap rates, could go up if the economy slows or interest rates rise or if investors decide to reduce allocations to the sector. It’s no sure thing that any of those things happen, but there is a greater chance that yields go up than down over the next decade. If cap rates rise, values would go down and some properties might qualify for less debt at refinancing.

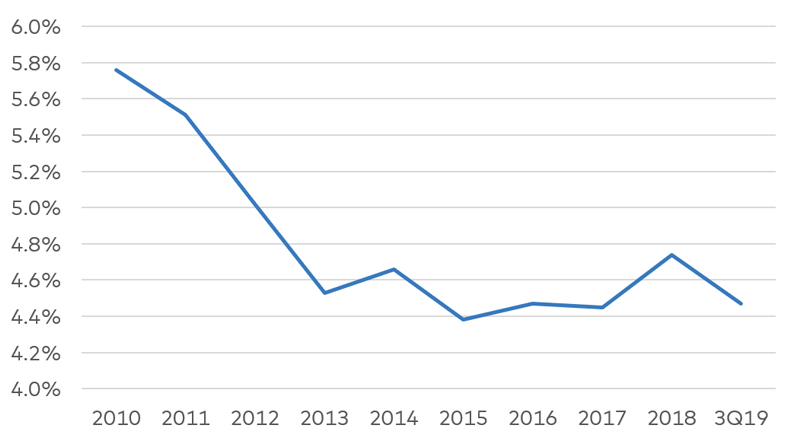

Low loan coupons are another potential trouble spot at maturity. The weighted average coupon of CMBS loans dropped to 3.7 percent in the fourth quarter of 2019, after averaging 4.5 percent in the first three quarters. Coupons have steadily dropped since averaging 5.8 percent in 2010 (CREFC/Morgan Stanley).

Low coupons enable property owners to borrow more proceeds with smaller monthly payments. That decreases the likelihood of defaults during the term of the mortgage since payments are a lower percentage of net income. However, if interest rates (or loan spreads) rise, the exit for loans originated today will have higher coupons that would make refinancing more difficult, especially if property income growth is flat or negative.

These issues are exacerbated by the growth in IO periods in loans, one of the metrics that has become more aggressive in the current cycle. During a time when leverage is restrained, offering full or partial IO periods is one of the ways lenders compete for business. More than four out of every five (82.6 percent) CMBS conduit loans had some IO period, and more than half (54.5 percent) were fully IO through three quarters in 2019 (CREFCC/Morgan Stanley). The number of loans with IO periods has increased steadily since the beginning of the cycle. In 2015, for example, only 23.7 percent of loans had full IO periods and 67.1 percent had some IO.

CMBS Weighted Average Coupon

Need to Maintain Standards

By most standards, the commercial mortgage market is extraordinarily healthy. Volume is high and distressed debt investors don’t have much to do. It’s unlikely those conditions will change soon. That would require an economic downturn or precipitous rise in interest rates that doesn’t appear to be in the cards in 2020.

That said, lenders still should underwrite loans with caution. The industry has eradicated the practice of pro-forma underwriting―assuming optimistic income growth projections―that was common in the run-up to the 2008 financial crisis, but it remains imperative to plan for downside scenarios. Speaking on a panel at the CRE Finance Council’s recent January Conference, Stewart Rubin, head of strategy and research for New York Life Real Estate Investors, noted that potential pitfalls include rising unemployment, increases in property taxes and municipal fees, higher labor and energy costs, and growth in capital expenditures. Lenders should underwrite credits that can withstand rising rates or an economic downturn during the loan term.

―Paul Fiorilla is director of Research for Yardi Matrix.

You must be logged in to post a comment.