Is Development Still Financeable? That Depends.

With banks limiting construction loans, potential projects require multiple, pricey sources.

Between high interest rates, rising construction costs and tighter loan requirements, completing commercial development projects within a budget that meets profitability expectations is harder today than it has been in more than a decade.

Interest rates are at a 23-year high, and commercial real estate delinquencies on banks loans are the highest since 2015, rising to 1.18 percent in the first quarter of 2024, according to Federal Reserve economic data.

Therefore, banks and credit unions with high CRE exposure are under greater scrutiny by bank regulators, causing them to tighten their construction lending terms or leave this market altogether, said Benjamin Kadish, founder & president of Chicago-based Maverick Commercial Mortgage Inc.

The reluctance of banks to lend for CRE projects is primarily due to the low level of loan payoffs they’re experiencing, which limits the amount of capital available to recycle back into the lending market, according to Shlomi Ronen, founder & managing principal at Los Angeles-based Dekel Capital, a real estate merchant bank.

“They have a bucket of capital that typically will turn over three or four times a year, but they had been seeing little to no pay offs in that loan portfolio, so there wasn’t any replacement capital to lend,” Ronen explained.

READ ALSO: JLL Revises Its 2024 Construction Outlook

On top of that, he noted that bank stocks plummeted, leaving banks unable to raise more capital to lend. Meanwhile, stricter regulations that would require banks to increase their loan reserves are looming.

“The bank pullback is forcing developers to either put in more equity upfront or take on more expensive debt by adding additional layers to their capital stacks,” Kadish continued. “As a result, managing cash flow has become a delicate balancing act, rife with uncertainties and potential pitfalls for developers as they navigate a dynamic and competitive market to ensure project viability and profitability.”

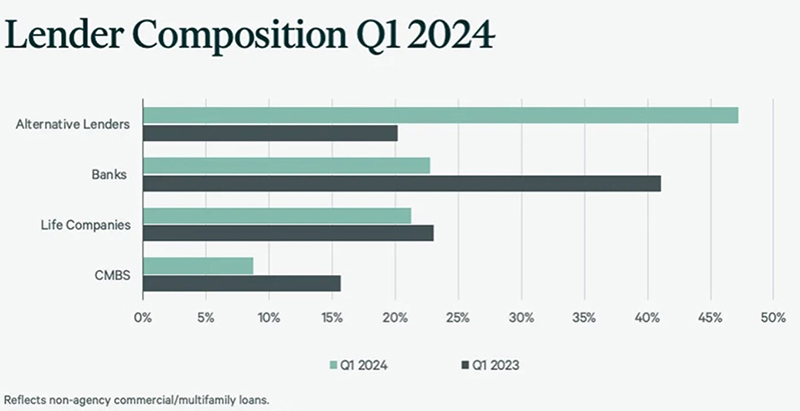

Non-bank construction lenders are gaining market share in the construction market because their capital and risk tolerance are more discretionary than banks, said J.D. Blashaw, vice president at Orange County, Calif.-based MetroGroup Realty Finance.

A complicated web of capital

Northspyre, a decision-making and intelligence platform for real estate developers, reported that from January 2022 to June 2024, the number of projects facilitated on its platform with more than three different capital sources increased by 57 percent, and the number of projects with more than five capital sources increased by 65 percent.

“Private equity funds, hedge funds and family offices are stepping in to fill gaps, offering more flexibility and speed compared to banks,” said Northspyre founder & CEO William Sankey.

The most common non-bank source of capital used by developers is private CRE debt funds, which offer more flexible loan structures than traditional banks, making them ideal for projects with higher risk profiles or those needing unique financing solutions.

According to Kadish, debt funds commonly fund loans from $1 million to $10 million, but some provide $10 million to $40 million. Debt funds focused on the institutional market are making loans up to $200 million, he said.

Jeff Saul, general manager at Built Technologies, a construction finance management platform, pointed out that large institutional funds can take on more real estate lending than banks and other alternative lenders, especially for construction due to its higher risk profile.

Alternative capital sources, however, come at a significantly higher price than bank financing, Blashaw stressed. He noted that the best pricing with banks today is either Prime based on the Secured Overnight Financing Rate at 5.5 percent, plus 2 to 3 percent. Debt funds and structured finance companies charge 2 to 4 percent more and typically charge a higher loan origination fee and sometimes an exit fee at payoff, Blashaw said.

Institutional investors, such as pension funds and insurance companies, finance construction projects out of their fund vehicles, charging similar rates and fees as other funds, Ronen said. “While they’re not necessarily cheaper, sometimes they have construction department financing that will do a balance sheet that generally starts pricing right around SOFR 3.5 percent plus or minus,” he noted

He noted, however, that debt funds also have tightened their underwriting standards, providing capital for projects built to an 8 percent return on cost but are no longer considering projects built at a 6 percent return to sell at a 4 percent to 5 capitalization rate.

Kadish also noted that many construction lenders have rolled back their loan-to-cost ratio from 75 percent to 50 percent or even less, making deal financials tighter and in need of more equity capital. To make financing feasible, many project sponsors are using preferred equity and municipal incentives, along with additional sponsors to fill equity gaps, he said.

Higher LTV at a cost

Developers also are leveraging off their projects or bringing in equity partners, such as institutional investors, funds, and family offices, to satisfy increases in loan-to-value requirements, Ronen said.

Saul noted that while banks charge significantly less interest, their loan-to-value is currently 40 to 50 percent. Meanwhile, funds will finance at 65 percent or more of the project cost, depending on the asset class and location. “This has obviously increased the use of funds for projects, but it’s also caused less projects to pencil,” he added, noting that today’s high financing costs inflate budgets and put downward pressure on developer yields.

The real issue is an increase in development costs across the board. This includes the hard and soft costs, such as interest rates, and operating costs on the completed development—personnel, repairs, real estate taxes, insurance, utilities and so forth, which often outrun current rents that developers can charge tenants, said John Barkidjija, executive vice president at Chicago-based Byline Bank, who heads CRE & specialty finance. “This is making it difficult for projects to generate an adequate return, especially given the increase in cap rates, driven by higher long-term interest rates” Barkidijia remarked.

As a result, lots of projects on the drawing board since 2021 will not be developed until there is significant demand for the product, which will raise projected rents for those projects, Kadish noted.

MetroGroup Realty Finance, for example, recently had two clients put retail projects on hold. Noting that while both projects had initially looked very viable, with 75 to 80 percent of space pre-leased, Blashaw explained, “the lower loan-to-cost ratios, combined with the increased cost of capital, certainly gave these developers pause.”

“Developers often justify the increased costs with trending rents, while in many parts of the country the opposite is happening—rents are flat or down,” Barkidijia added, noting that in those instances, there is a disconnect between the developer’s optimism and prudent bank lending standards. “Banks respond by reducing the relatively inexpensive leverage offered to the developer, forcing them to infuse more expensive capital into the project, which further pressures the returns to the developer and equity partner,” he said.

Barkidjija suggested that there are only two scenarios in which bank leverage will increase back to recent historical levels. The first is that over time, the increase in costs to develop and operate projects will slow down enough so that actual rents achieved will catch up and provide returns that satisfy prudent bank underwriting. The second is uniqueness, where there is a rare submarket in which the supply/demand equation and the strength of the local submarket’s rents provide a return that satisfies prudent bank underwriting.

“The challenge for developers is to find a bank astute enough to recognize the difference between ordinary and unique” Barkidjija continued. ”This is why it is so important to partner with a bank that has deep expertise in commercial real estate, as well as specialization in your target asset class, across a variety of market cycles. This industry expertise, combined with a bank that is structured in a way to really get to know the customer, market and the asset, helps ensure a comprehensive, nuanced evaluation of the deal.”

US to the rescue

Sankey also suggested that government programs like low-income housing tax credits and incentives for transit-oriented developments also are becoming more attractive to developers because they provide financial benefits that can significantly improve project feasibility. Benefits include direct funding, such as a U.S. Department of Transportation Pilot Program for TODs, which offers cost-sharing or matching funds up to 80 percent of the project cost or 100 percent federal support for affordable housing TODs.

Local governments also offer incentives for TODs and affordable housing, including fee waivers, expedited permitting, reduced parking requirements and density bonuses. While inclusionary zoning ordinances can specify a percentage of new units that must be affordable for targeted incomes, density bonuses and other incentives for creating affordable housing units help to offset lower rents for the affordable units.

Ronen noted that some developers are taking advantage of C-PACE, a green bank program that finances aspects of a project that affect building performance or water conservation. “The challenge with C-PACE financing is that it doesn’t ultimately give you additional leverage,” he said. “But if your senior lender is charging a rate higher than C-PACE, then it becomes accretive for you to explore C-PACE financing and bring in a smaller amount from your senior lender.

According to Ronen, C-PACE is currently priced similar to bank financing, 7 to 7.5 percent plus or minus, but requires no equity. Rather, it utilizes a public financing mechanism that allows debt to be repaid as a benefit assessment on the property tax bill over a term that matches the useful life of improvements or project infrastructure (typically 20 – 30 years) and can be transferred to new owners as a property lien.

While the national banks remain on the sidelines for construction financing, Ronen said, both local and regional banks are now showing a willingness to quote construction loans, especially for a multifamily.

Barkidjija noted that some banks are reducing their CRE exposure due to scrutiny by regulators and equity markets for rising delinquencies and elevated concentrations of CRE exposure, but many banks still have the capacity and willingness to lend to experienced sponsors for high-quality projects in locations with barriers to entry and strong supply/demand dynamics.

While banks are beginning to provide more construction financing than they did 12 months ago, Ronen noted that they are tightening terms and adding things to term sheets that weren’t there 24 months ago, such as deposit relationships, which require project sponsors to deposit a certain amount of money in their banks before their loans are approved.

Ronen, for example, is currently working on a $40 million bank loan that requires his client to transfer $6 million in deposits to the lending bank. “This particular bank is providing a 24-month loan with two extension options,” he said, noting that his client asked for this, as it’s not uncommon for banks to provide a 36-month initial term, which makes the loan more profitable for the bank.

Ronen noted, however, that banks are only working with high-quality, creditworthy developers, so “if you’re not bankable, then you’ve got to go private. It’s higher priced, but it’s available.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.