Keeping Dry

How to manage the risks of increased moisture in green buildings.

How to Manage the Risks of Increased Moisture in Green Buildings

By Brad Berton, Contributing Writer

As summer turned to fall, Houston’s Class A office market was on fire—with numerous LEED pre-certified speculative and build-to-suit developments on the way or soon to be. In Houston and other Gulf Coast cities, the change in season does not entirely relieve a key problem in these high-profile projects: These locations stay wet and humid for much of the year.

Throw in today’s complicated building envelopes, heavy-ventilation HVAC systems and insufficiently understood new-wave building materials, and moisture-intrusion issues are arguably inevitable in today’s greenest buildings in numerous Southeastern markets.

Unintended consequences of tapping the most sustainable materials, techniques and technologies can include considerable water damage and even health-threatening mold contamination, and in turn legal liabilities and related losses, cautioned veteran real estate and construction attorney Eugene Heady, a partner at Smith Currie & Hancock.

Indeed, as the green building movement transitions from cutting-edge to mainstream with the coming development wave, the increased complexity of high-performance projects often creates very challenging moisture-intrusion risks, added longtime construction defect specialist George DuBose, vice president of consulting services with Liberty Building Forensics Group.

“Green initiatives take something that’s already a management-intensive process (construction) and make it that much more complex,” DuBose observed.

DuBose and Heady addressed moisture intrusion and other such hidden risks associated with sustainable development—and identified viable mitigation measures—in a recent webinar sponsored by WPL Publishing Co., which serves the construction disciplines with emphasis on green building and legal issues.

They identified multi-faceted envelopes, heavy ventilation and unproven materials as some of the more daunting risks facing green-minded commercial developers, especially in those markets experiencing high heat and humidity for much of the year.

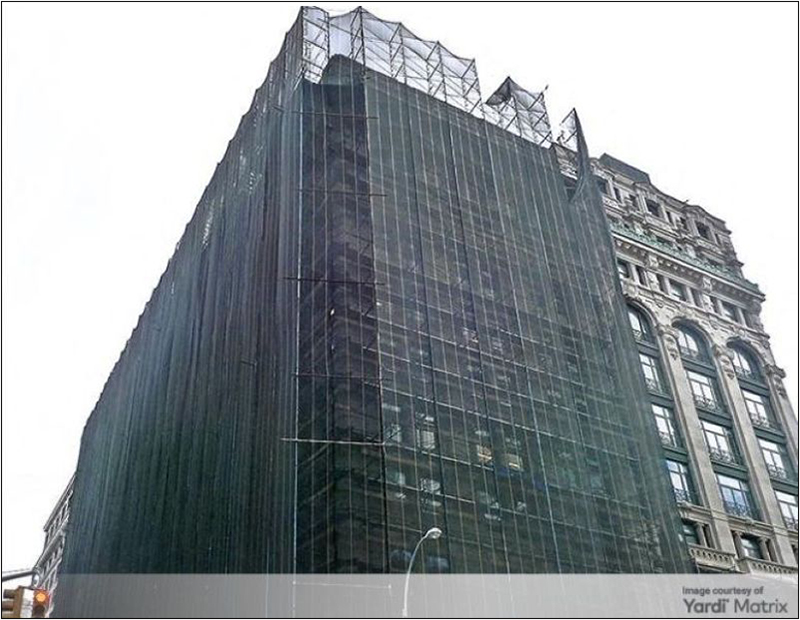

A modern green office tower’s multi-dimensional wall and roof assemblies include hundreds or even thousands of “termination and transition points” where structural members connect to cladding, skin material gives way to glazing, roofing materials transition to solar-panel housings and so forth. These represent the most likely locations of envelope breaches leading to bulk water intrusion, DuBose noted, exacerbated by the many individual parties involved in designing, producing and installing wall and roof assemblies.

Modern sustainable features such as operable windows and green roofs can also increase risks of water intrusion. Rainwater as well as untreated humid air can penetrate envelopes via operable windows, while green roofs run the risk of allowing moisture migration and concentration between impermeable membranes.

So how can developers and their architects, engineers and contractors minimize such issues?

Heady and DuBose offer plenty of advice for minimizing failures—perhaps including additional performance bonding and even extended contractor and product warranties. But generally they also stress substantial and early planning among multiple participants to identify a given project’s sustainability objectives, as well as to quantify, mitigate and equitably spread the various related risks.

They even suggest devising a detailed green building risk management plan that provides extensive guidelines for the design and construction team from concept through warranty periods. In addition to the principal designers and contractors, contributors might include commissioning professionals and other green building specialists, moisture control experts, key subcontractors, materials suppliers and procurement pros, attorneys—even insurance companies.

For his part, Allan Skodowski, director of LEED and sustainability with efficiency-minded Transwestern, typically requests that contractors double the initially specified thickness of green roof membranes installed at Transwestern-managed buildings, and also requests that contractors assume responsibility for failures for 20 years. “The last thing you want to see is roots growing into the membrane after two years and causing a leak so you have to pull up 10,000 square feet of roof and membrane to find it.”

Mitigating risks inherent in modern green-building technologies is mostly a matter of prudent installation oversight and ongoing maintenance, stressed Skodowski. Rather than overly complex envelopes, human errors such as use of the wrong sealant for the job or improper flashing materials and techniques are what typically lead to water infiltration, he insisted.

High-Performance HVAC

In pursuit of greater energy efficiency and healthier interior environments, developers of high-performance office buildings typically spec state-of-the-art HVAC systems featuring exceptionally high-volume ventilation mechanisms. Indeed, green buildings often bring in 30 percent or more outside air than ASHRAE standards specify, DuBose noted. But perhaps predictably, building technologists have likewise identified a clear correlation between higher mechanical ventilation and greater moisture-intrusion issues.

Logically, the most effective solution here is to design HVAC systems that distribute comfortable air to desired breathing zones, but without inadvertently causing moisture-intrusion problems. And that may well entail even more complex and powerful HVAC components and control systems capable of dehumidifying outside air flowing into the building.

“You should never increase air ventilation without an overriding control of both pressurization and dehumidification,” DuBose stressed.

And it will also help to more explicitly verify HVAC system performance through commissioning efforts, as well as post-construction start-up tests featuring detailed “pressure-mapping” confirming proper air distribution. Building operators should also closely monitor temperature and relative humidity during early occupancy months, including in often-ignored building cavities.

As developers continue to experiment with green improvements, DuBose offers one potential partial solution that has not received enough attention to date: peer review. While the prevailing professional feedback system is downright “horrible,” he suggested that a thorough assessment of a project’s design, techniques, technologies and materials by multiple experts—before construction commences—can greatly reduce the risk of system failures.

“The strategies that have the greatest impacts over ultimate performance

come early in the design process,” DuBose concluded.

The Takeaway

✔ Green materials, technologies and techniques carry greater risk for moisture intrusion.

✔ Early planning and a risk management plan can make

a difference.

✔ Improving currently poor

peer review could greatly reduce risk of system failures.

You must be logged in to post a comment.