Last-Mile NIMBYism Is a Headache. Remedies Are Available.

How mixing new and time-tested tactics can yield entitlement success.

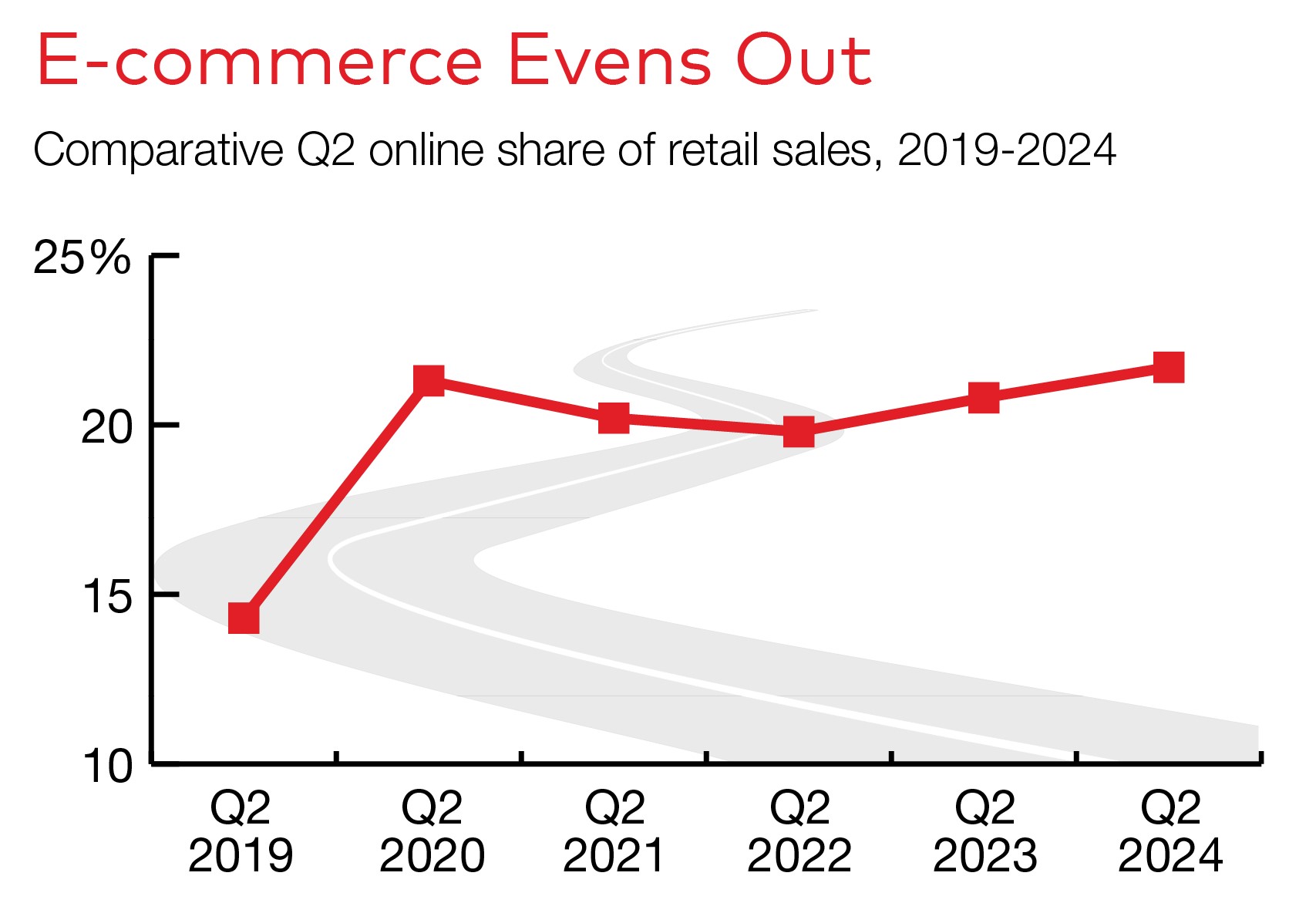

The increasing number of products arriving via van is generating greater demand for warehouses, both of the last-mile and bulk variety. In the second quarter of 2024, online sales totaled nearly $292 billion, a year-over-year increase of 6.7 percent, according to the U.S. Department of Commerce. Digital Commerce 360 estimates that e-commerce averaged 21.7 percent of all retail sales, up from 14.3 percent in the second quarter of 2019.

But that demand also creates a paradox: The same consumers who take advantage of shopping digitally often chafe at proposed distribution center developments. That’s creating headaches, extra time and expense, and uncertainty for developers. “People complaining at city council meetings is nothing new—they might like the jobs a project brings, but they don’t want it near their home,” said Seth Martindale, a senior managing director of Americas consulting with CBRE in Los Angeles. “But we’ve seen an uptick in opposition, and a few projects here and there across the country have been blocked. That’s problematic for growth.”

To some degree, the ramped-up resistance is in response to the explosion in e-commerce during the pandemic. In turn, that drove unprecedented industrial market growth for a couple of years. “We did five years’ worth of leasing in two years—1 billion square feet,” said Craig Meyer, president of industrial brokerage for the Americas at JLL. “The demand fueled more warehouse construction, including last-mile distribution to deliver products overnight.”

Creeping regulation

While the once-torrid pace of development has slowed, some warehouse opponents have moved beyond fighting individual proposals to pressing lawmakers for stricter controls on construction.

- California Gov. Gavin Newsom recently signed legislation that will limit construction of warehouses close to homes, schools and hospitals.

- New York City officials have committed to developing a “holistic industrial strategic plan” that will include new rules to guide last-mile warehouse development.

- New Jersey lawmakers have drafted legislation—none yet passed—to address what critics consider runaway warehouse growth.

At the center of such efforts are typically environmental concerns, particularly emissions from delivery vehicles in populated areas and low-income neighborhoods. But pushback against new warehouses is also popping up in rural areas where developers are eyeing ground-up, greenfield projects. That trend, observers say, suggests that the prospect of change is the primary cause of opposition.

In New Jersey, residents and officials who are often unaware of zoning laws that allow warehouse development by right have rejected projects, said Dan Kennedy, CEO of NAIOP New Jersey. Yet developers can sometimes revive these proposals through litigation. In August 2023, for example, the state superior court reversed the denial of a 2.1 million-square-foot warehouse park in Harrison Township, N.J., a rural suburb southeast of Philadelphia. The court’s opinion termed the township’s decision to rebuff the proposal “arbitrary, capricious and unreasonable,” The Sun Newspapers reported.

In a March 2024 decision, a New Jersey superior court judge disqualified eight of nine planning board members from deciding the fate of a 660,000-square-foot warehouse in Sparta, a town in northern New Jersey. It turned out that a conflict of interest had emerged—the board members were part of an online group fighting the project.

“The reality is that the entire logistics community is under an increased level of scrutiny,” Kennedy noted. “There seems to be unanimous opposition—the farther out you go, the harder it gets, and the new narrative around environmental justice means you can’t build where people live. We don’t mind targeted growth or being surgical about expectations, but we’re inching our way toward a no-growth agenda.”

Make the case

To address environmental-related resistance, developers can point out that the alternative to more e-commerce facilities would be more cars traveling to stores and generating more pollution. That’s the advice of Donald Bredberg, managing director of StoneCreek Partners, a Las Vegas-based commercial real estate planning and entitlement consultant. In some cases, his firm has arranged meetings between project opponents and logistics companies, which are able to quantify the amount of e-commerce activity in the area.

“Someone who is well-meaning but against the project from an environmental standpoint realizes, ‘It’s not the developer that’s the problem, it’s my preference for how I’m receiving my goods,’” Bredberg added. “It’s one of those be-careful-what-you-wish-for consequences, and we all need to be part of the solution.”

Often, however, developers fail to make their case. Opponents recently were able to kill a last-mile warehouse proposal in Pennsylvania when the developer didn’t effectively counter arguments against the project, said Bredberg, who was working with the local government to determine the best use for the site.

One way to help secure the approval of warehouse projects is to begin working early with the community and elected officials. That’s an effective way to gauge their potential concerns and educate them on what activities will take place in and around the building, said Amanda Brown, founder of HD Brown Consulting.

Even in her pro-business state, Brown reported, residents are pushing back against warehouse projects along the Interstate 35 corridor, the north-south route that runs from Texas to Minnesota. The objections stem from concerns about truck traffic, noise, lighting, landscaping and building walls—anything that might affect property values. As a result, negotiations typically begin with developers showing a willingness to exceed building codes related to those elements through such measures as upgrading exteriors and planting extra trees, she said.

“A ton of land has been entitled for industrial and warehouses here, and communities feel like it’s oversaturated,” recounted Brown, who recently helped shepherd an Amazon last-mile distribution center in Round Rock, Texas, through the entitlement process. “In most of my projects, whether it’s residential, commercial or industrial, I’ve found that neighbors are going to be resistant to change. So I do a lot of outreach.”

Community transformation

Perhaps nothing illustrates how e-commerce is changing landscapes better than California’s Inland Empire. Onetime dairy farms are now full-fledged communities with warehouses that link the Los Angeles and Long Beach ports to the rest of the country.

“Developers by and large are smart people—they have families and understand the concerns surrounding warehouses,” stated JLL’s Meyer, who is based in Los Angeles. “So we’ll work with communities and we’ll get them done.”

In the heavily regulated state, developers already face a two-year-plus entitlement process and the new law will add another layer of rules. But Meyer expects growth to continue.

You must be logged in to post a comment.