Micro-Fulfillment Centers Present Big Opportunities

Driven by surging e-commerce demand, the rise of urban micro-fulfillment centers creates new opportunities and challenges for the real estate industry.

What does a small urban warehouse have in common with a gym, a shopping mall and the backroom of a grocery store? All of these properties could become home to flexible logistics hubs known as micro-fulfillment centers, which are designed to speed up and augment deliveries to America’s surging base of online shoppers.

“It will shortly become the norm for the majority of general merchandise products, that your options are to pick in-store, or to automate with giant vending machines like Fabric,” says Steve Hornyak, the company’s chief commercial officer. Image courtesy of Fabric

Over the last couple of years, the niche product at the intersection of real estate, supply chain management and technology has attracted growing interest from investors as an array of startups roll out their networks of MFCs across the country.

“You still have massive, million-square-foot facilities being constructed across North America,” said Blaine Kelley, senior vice president of CBRE’s global supply chain practice in Atlanta. “The retailers and consumer goods companies have to inventory large stock-keeping units (SKUs) and amass those closer and closer to population centers.”

While that infrastructure of huge distribution hubs is still maturing, micro-fulfillment sites are just starting to gain traction, but the two property types appear to be complementary. “The large regional facilities are feeding the micro-fulfillment networks,” said Kelley. “So they’re both being built out at the same time.”

Hungry customers

An employee fills a grocery order as robotic totes scurry around in Fabric’s 18,000-square-foot underground warehouse in Tel Aviv, Israel, which features three temperature zones. Image courtesy of Fabric

Measuring the size and scope of the phenomenon is challenging, owing to the novelty of the concept and the way it blurs the line between different property types. Does an MFC in a shopping mall count as retail or industrial real estate? The task is complicated by a slew of overlapping industry jargon, from “last-mile delivery centers” to “urban logistics” and “back-of-store.”

Steve Hornyak, chief commercial officer of robotic micro-fulfillment startup Fabric, estimates that the number of MFCs serving the grocery industry alone will grow from dozens currently to thousands within five years, as food retail continues to move online.

E-commerce jumped from 3.4 percent of total U.S. grocery sales in 2019 to 10.2 percent in 2020, greatly accelerated by shelter-in-place behavior during the pandemic, according to a survey released last September by grocery e-commerce platform Mercatus and research firm Incisiv. That figure is projected to rise further and reach 21.5 percent by 2025.

Hornyak noted that the industry expects e-commerce penetration of grocery sales to reach 20 percent within two to three years. The dramatic growth has forced grocers to pay attention. “At 10 percent it’s meaningful. At 20 percent it’s paramount.”

As a result, many grocers are starting to look at strategically shifting from manual, in-store fulfillment of e-commerce orders to leveraging automation—whether through in-store, local or regional facilities—to boost their capacity and efficiency in serving online shoppers.

REEF Technology, which turns underutilized commercial spaces such as parking infrastructure into logistics hubs and neighborhood kitchens, teamed up with DHL Express last year to pilot the use of electric-assist cycles for sustainable pickup and delivery in Miami. Image courtesy of PRNewsfoto/DHL

Small is beautiful

The need for rapid fulfillment is acute with perishable goods like groceries, but the logic driving MFC deployment applies to general merchandise as well. Last year, technology firm Fillogic teamed up with mall owners Brookfield Properties, Macerich, Simon Property Group and Taubman to open micro-distribution centers at seven major retail properties in New Jersey and Connecticut.

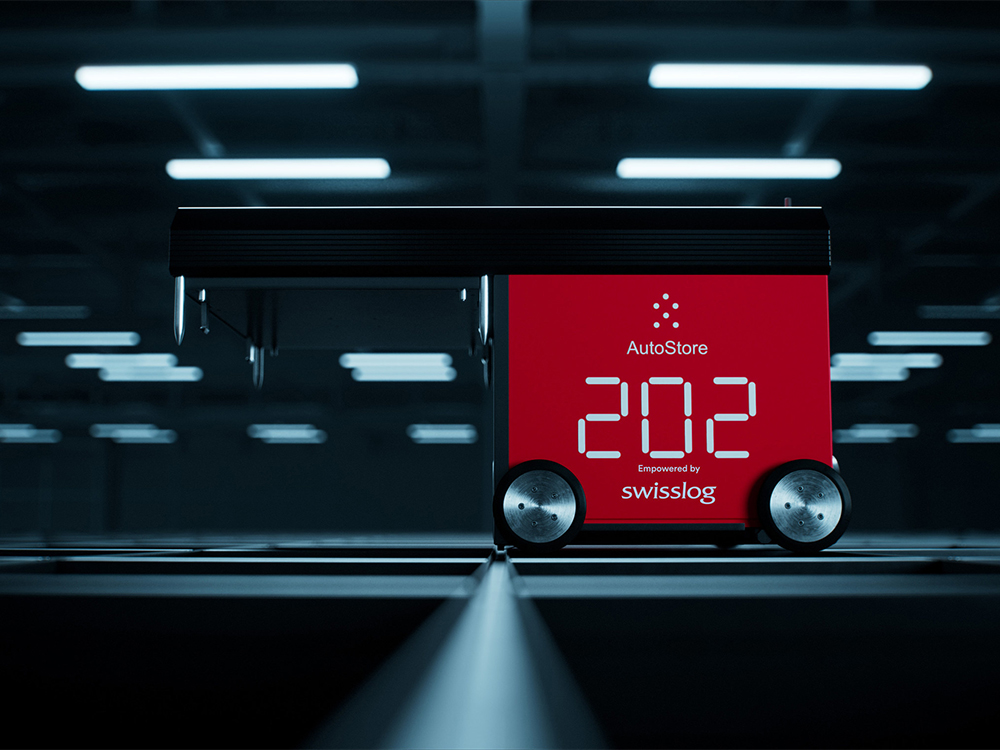

Warehouse automation and software firm Swisslog partnered with Texas-based supermarket chain H-E-B last year to deploy new micro-fulfillment centers featuring AutoStore, a robotized solution for efficient storage and order processing. Image courtesy of Swisslog

Other expanding players in the MFC world include warehousing startup Ohi, which provides technology for e-commerce brands to operate urban micro-fulfillment sites measuring anywhere from a few hundred to a few thousand square feet. The company has locations in Manhattan, Brooklyn, N.Y., Chicago, Los Angeles and San Francisco, according to its website.

Small, flexible fulfillment centers, whether automated or manual, could satisfy a growing appetite in dense metropolitan areas for deliveries in windows of time as short as one hour. Continued innovation in the supply chain—from complex data analytics to robotics and autonomous transport—is likely to create new uses for these facilities.

“If the future of the world looks like semi-autonomous truck platoons going down the road with no driver, they can only go down the ramp and into the loading dock; they can’t really navigate around town,” said Steve Weikal, CRE Tech Lead at the MIT Real Estate Innovation Lab.

“So the progression from regional distribution to local distribution, to one of these micro-distribution facilities—even in the suburbs—I think it’s going to be complimentary. It’s going to make the overall system much more fluid and efficient.”

Reinventing spaces

Fabric’s micro-fulfillment centers, like this new facility in Brooklyn, N.Y., take up a fraction of the space of traditional automated sites, which tend to be about 10 to 20 times the size. Image courtesy of Fabric

Opportunities for real estate investors are beginning to emerge as the explosive growth of e-commerce generates demand for MFCs. “There’s a lot of capital that wants to get in that game,” said Kelley, noting that private equity firms, property developers and institutional investors are evaluating the market.

But setting up miniature logistics sites in a densely occupied city may present more challenges than operating a big rectangular building an hour outside of a population center. Possible roadblocks include finding adequate parking space for both employees and delivery trucks and gaining municipal support for a logistics operation in a residential area.

On the other hand, a wide range of property types could lend themselves to micro-fulfillment uses. “The logical one is going to be some sort of a retail facility that was in a good location, has good access and either the concept failed or the building shuttered,” said Kelley.

Parking garages also provide opportunities for urban fulfillment. Fabric operates four live sites in the U.S. and Israel, including an underground automated warehouse located in a parking structure in downtown Tel Aviv that spans 18,000 square feet with an average clearance height of 11 feet.

The company is expanding its network across the U.S., where it already has two live sites in New York City. “We use a very complex software that we built that actually maps out where these centers need to be,” said Hornyak, noting that cities with football teams tend to be attractive e-commerce markets.

Fabric is on the hunt for existing spaces measuring 10,000 to 30,000 square feet, with ceiling heights of at least 12 feet and ideally 16 to 30 feet. That is large enough to accommodate its equipment, which essentially comprises giant, high-tech vending machines.

Hornyak noted that the firm can open its facilities in old gyms, big-box stores or small warehouses. “The types of repurposing in the places we’re looking at doesn’t really matter as long as we can get the zoning associated with it.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.