Sizing Up New York City’s Far-Reaching Climate Bill

Real estate investors, developers and advisers are assessing the legislation, which is being praised for its boldness and criticized for focusing on large and medium-sized properties.

America’s largest city is rolling out one of the most aggressive policies to curb greenhouse gas emissions ever attempted by a major municipality. The Climate Mobilization Act, passed by the New York City Council on April 18 by a 45-to-2 vote, quickly drew a wide spectrum of praise and criticism.

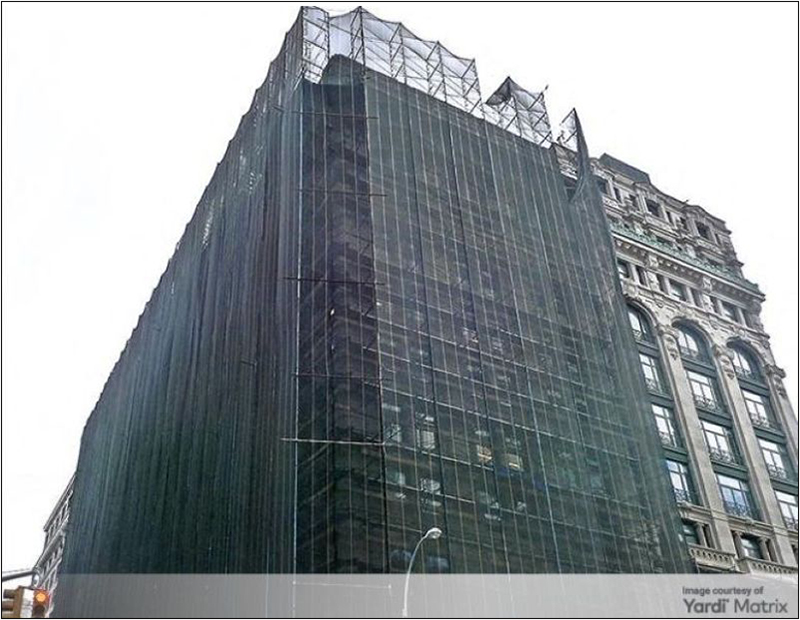

The crux of the legislation is a bill, Introduction 1253-C, that would require the city’s large and medium-sized buildings to slash their greenhouse gas emissions by 40 percent by 2030 and 80 percent by 2050. The policy would apply, with exceptions, to buildings measuring 25,000 square feet or larger—amounting to 57 percent of the city’s built area, or tens of thousands of buildings, including landmark skyscrapers such as the Empire State Building and One World Trade Center.

The bill sets emissions limits based on the usage of the building and mandates cuts from the highest-emitting 20 percent of buildings in each occupancy group by 2024. The other 75 percent of buildings in each group need to meet reduction targets beginning in 2030. Landlords could face steep fines for buildings that exceed the caps. The bill also creates a new office within the Department of Buildings to oversee implementation of the program.

Buildings are estimated to account for nearly 70 percent of New York City’s carbon pollution and efforts to make the built environment more green-friendly have been underway for a long time. In a recent milestone, de Blasio joined mayors of 18 other cities worldwide last August in signing the Net Zero Carbon Buildings Commitment that requires all new buildings to operate at net zero carbon emissions by 2030.

NYC praised for carbon leadership

Many have hailed the new legislation as a groundbreaking move to reduce the carbon footprint of a city that generates $1.5 trillion in annual economic output.

“It’s one of the boldest measures ever taken by a city to address energy efficiency and climate change,” said Cliff Majersik, executive director for the Institute for Market Transformation (IMT), in a conversation with Commercial Property Executive. Along with the Clean Energy DC Act that went into effect in Washington, D.C., last month, “it’s the only measure that’s trying to address whole-building performance of existing buildings, even buildings that aren’t pulling permits. That’s really what’s needed.”

Majersik noted that only around 2 percent of building stock is being built or turned over every year. “If you want to meet the kind of climate commitment that cities like New York have made, you’re going to need to dramatically improve the energy efficiency of the buildings that are standing today.”

In a blog post, Majersik observed that the hard work of implementation and rulemaking remains. “This will not be a light lift and will greatly affect the bill’s impact on emissions, jobs and health,” he commented. “If implementation successfully harnesses energy efficiency, it will lead to renovations to add insulation, upgrade heating and cooling equipment, replace lighting, fix roofs and countless other improvements. The Mayor’s Office of Sustainability estimates that the bill will create 23,700 new green jobs by 2030.”

Critics take aim at bill’s priorities

Others have blasted the Climate Mobilization Act for what they see as its inadequacy and lack of balance. The Real Estate Board of New York (REBNY), a trade association that represents the real estate industry, faulted the bill for singling out larger buildings while exempting a wide range of properties from the caps, including houses of worship, income-restricted coops, buildings with rent-regulated units, public housing and city-owned buildings.

The association also noted that the strict, fixed caps would make it harder for buildings to accommodate growth, as increased occupancy translates to more energy usage and a greater likelihood of exceeding the carbon caps. REBNY said that landlords would incur a cumulative cost of at least $4 billion to make the upgrades needed to bring their buildings into compliance.

“The real estate industry and other stakeholders support the goal of reducing carbon emissions 40 percent by 2030,” commented REBNY President John Banks in a prepared statement. “Unfortunately, Intro 1253 does not take a comprehensive, city-wide approach needed to solve this complex issue.” The bill will fall short of achieving the targeted reduction by including only half of the city’s building stock, he added.

You must be logged in to post a comment.