Office Distress Reopens the CMBS Bargaining Table

How will borrowers, lenders and special servicers find workout solutions for troubled assets?

As the amount of distressed debt in the commercial real estate sector climbs, all eyes are on growing loan defaults.

At the start of 2023, some $1.9 trillion in property debt was scheduled to mature through the end of 2025, and loans bundled in CMBS accounted for more than $350 billion of that total, according to Newmark’s capital markets report for the first half of 2023. The bulk of those maturities—$163 billion—was due this year, Newmark noted. MSCI Real Assets estimated that about $100 billion remained in the second half of 2023.

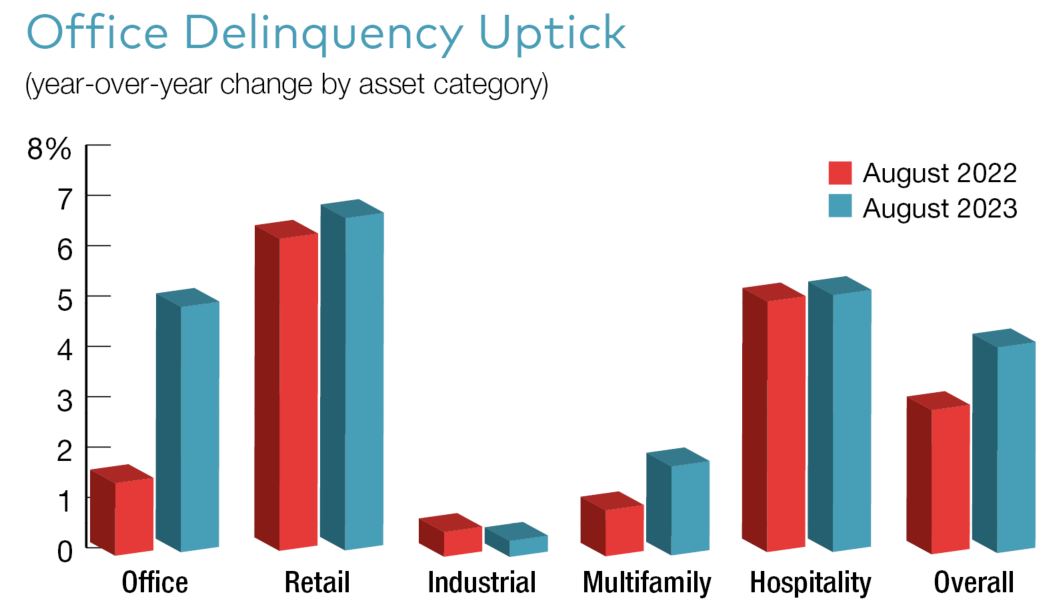

At the same time, CMBS distress continues to mount, predominately driven by office troubles amid high interest rates, empty buildings and plunging values. In September, the special servicing rate for office hit a six-year peak after spiking 491 basis points year-over-year, according to Trepp. The office delinquency rate rose about 360 basis points to nearly 5.1 percent in August from a year earlier, while the special servicing rate increased some 455 basis points to more than 7.7 percent. Although the delinquency rate for retail was 180 basis points higher than it was for office, the pattern was considerably different. In contrast to the office sector, the retail rate had fluctuated slightly during the preceding 12 months and had increased only 42 basis points overall.

Kicking the can

Because of the lack of price stability, observers suggest that a methodical loan modification, rather than foreclosure, is the appropriate approach to resolving troubled office mortgages. Regulators are encouraging the tactic. In June, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., the Federal Reserve and other agencies encouraged banks to work with creditworthy borrowers in distressed times by reiterating and updating guidance originally introduced in 2009.

“In my opinion, office distress is going to be handled differently than, say, multifamily distress,” said Joseph Iacono, CEO & managing partner of Crescit Capital Strategies, a private lender and workout advisory. “Assuming that borrowers are engaged in the process and aren’t turning in their keys, special services may be predisposed to kick the can down the road because the magnitude of doing otherwise could be really troubling.”

So far in 2023, CMBS parties have agreed to extend office mortgages with an aggregate loan balance of roughly $2.4 billion that is nearing maturity, according to Trepp. That equates to more than 70 percent of the $3.2 billion in all workouts this year.

Lenders typically demand that borrowers pay some amount as part of an extension, however. Owners of the Seagram Building at 375 Park Ave. received up to a two-year extension on its $1 billion mortgage—$783 million of which was securitized—on the eve of the loan’s maturity in May. But the modification requires the borrower to make periodic principal curtailment payments of $55 million, Trepp noted.

Despite the extensions, Iacono added, at some point the market must recognize that many office assets will be fetching lower rental rates as companies roll off their leases. But they will also need material capital expenditures to compete. All of that means prices have to reset.

“That’s a double whammy,” Iacono said. “The values have to capitulate, and they haven’t done so yet.”

Fundamental distinctions

Today’s special servicers and borrowers are working in a far different environment than they were during the financial crisis. That disruption shocked the credit markets to such an extent that debt wasn’t available at any price, said Jim Costello, chief economist for MSCI Real Assets Research.

While debt is much costlier today, and fewer lenders and borrowers are in the market, it is still available, he added. CMBS issuances of some $16.5 billion in the first half of 2023 marked a year-over-year decline of 67 percent, according to Trepp. That’s nowhere near the doldrums of 2009, when volume totaled just $2.8 billion for the entire year.

And there are other key differences with the Great Financial Crisis that shed light on today’s conditions. During the GFC, investors acquiring office assets that had fallen into distress from overleveraging could justify those deals because of material price discounts and, as was often the case, some amount of current income. They also rightly assumed that companies would begin hiring and leasing space once the recovery took hold, Costello said. That may not play out this time around.

“The distress during the financial crisis was due to a shock to the credit markets; today, we’re facing fundamental distress,” he observed. “There is a lot of uncertainty over the future of occupancy in terms of how many workers will come back to the office. You can’t just buy a distressed office and put the appropriate level of debt on it and await the recovery.”

Tribalism prevails

The removal of some challenges to reaching a workout agreement represents another difference between then and now, said Shlomo Chopp, an investor and workout specialist who recently launched Terra Strategies to invest in distressed CMBS. Controlling members in a CMBS trust who were exposed to losses previously had the right to buy defaulted CMBS loans at a discount, for example, which essentially gave them the power to stop workouts agreed to by the borrower and special servicer, he noted.

More recent CMBS trustees have removed the buyout right of the controlling members, which should have removed an impediment to finding resolutions. But so far, it has had little effect. Tribalism between borrowers and lenders remains “alive and well” in this economy, Chopp added, and borrowers today are largely negotiating from a weak position considering their unfamiliarity with the special servicer bargaining process and the market’s waning fundamentals.

Ultimately, an asset’s value will dictate the solution, Chopp stated. If it has value, then either the servicer will foreclose on it based on a conviction that it can get a certain price, or the borrower will agree to a modification that may value the asset above that price, which could still be too high.

“If there is no value in the asset, then that’s the hot potato,” he said. “We’re in uncharted territory in regard to how all this plays out. At some point, the servicer is going to have to do a deal. But the question is: Will the borrower want to do a deal?”

You must be logged in to post a comment.