Report: Walkable Urban Metros Leave the Suburbs Behind

America is walking again. Where are the most pedestrian-friendly economic centers in the U.S. and what's behind their robust growth?

Christopher Leinberger, Charles Bendit Distinguished Scholar and research professor at George Washington University and chair of its Center for Real Estate & Urban Analysis. Image courtesy of Christopher Leinberger

The most walkable urban place in America is … New York. That may not be a big surprise, but the other findings of the 2019 Foot Traffic Ahead report are. Denver, for example, is the second most walkable city. Moreover, there is a 30-50 percent cap rate premium in these walkable urban places over drivable suburban areas and a 75 percent rent premium.

The report, which is being released today by the Center for Real Estate & Urban Analysis at the George Washington University School of Business, ranks the 30 largest metros based on how much of their income-producing real estate is in walkable urban places, or “walkups,” of which the report finds there are 761 unevenly distributed throughout the U.S. The study also grades the growth potential of these 30 metros―Boston came out on top of that list—and their social equity performance.

Read Also: How Walkable Urbanism Is Changing CRE

CPE spoke to Christopher Leinberger, the Charles Bendit Distinguished Scholar and a research professor at GWU, prior to the report’s release about what is driving the wide value differential between urban and suburban and about the explosive growth of the most walkable metros.

New York is a given. Tell us about the other most walkable urban places.

You have New York, Denver, Washington, Boston, San Francisco and Chicago. Again, these are all metro areas.

The big surprise this year is the jump in Denver, and this is a result of 99 percent of all net absorption in Denver since 2010 until the end of 2018 in office, retail and multifamily being in the walkups. Almost zero went to business parks, regional malls and drivable suburban apartments. It’s pretty stunning.

Denver went from ninth to second since the 2016 Foot report. To what do you attribute such progress?

That is a big jump, and we think one of the major reasons for it was when John Hickenlooper became mayor. John, of course, is running for president right now, and he was governor of Colorado these last two terms. But before that, he was mayor, and before that, he had the best training to be a mayor I think possible: He ran and owned the largest brew pub in the entire state, and that brew pub was in LoDO (Lower Downtown), which was at that point the slum section around Union Station. It was a down-and-out freight yard and a Greyhound Bus Depot. It was beginning to stir, and part of it was John’s brew pub. Coors Field got built down there, as well.

John brought all the political leaders in the region together at his brew pub, got them a little drunk, and then said: “Look, what’s good for the city of Denver is good for the suburbs, and vice versa. What will we collectively do to improve this metropolitan area?” They decided the No. 1 priority was to put in a major rail transit system, and in six months they had raised $6 billion locally and started building it. We think that $6 billion investment is paying off in the jump in the walkable urban rankings. And I think it is just the beginning in Denver. Denver has everything going for it: a highly educated workforce, which correlates heavily with walkable urban metros, and it is gaining strength in the knowledge economy. Denver is one to watch.

What else was remarkable in this year’s study?

To me, the most interesting part of this is the Future Growth Momentum Index we have come up with. In the future growth rankings, No. 1 is Boston, No. 2 is New York, No. 3—a surprise in the 2016 but it continues to be there—is Detroit, No. 4 is Pittsburgh—another surprise, No. 5 is Washington, D.C., and Miami is No. 6. You look at Miami, Pittsburgh and Detroit and say: Where did they come from? And Detroit at No. 3 is entirely because of what’s going on in Downtown and Midtown Detroit. It’s just exploded.

And the person you can credit recently for Detroit’s turnaround is Dan Gilbert at Quicken Loans. In 2007, he raised the question of whether he should move his company downtown, and I started talking to him then. He moved his company Downtown in 2010, and GWU just analyzed the impact Quicken has had on the city and on the real estate, and it’s just been remarkable. That’s a man bites dog story.

In Pittsburgh, the vast majority of job growth has been driven into Center City. They don’t have much of walkable urbanism in the suburbs.

In Miami and Los Angeles, which was No. 10 for future growth, the two interesting things going on is those metro areas are reestablishing their rail networks. In 1945, metro Los Angeles had the longest rail transit system in the world. And by 1962, it was gone. They had ripped it out and replaced it with freeways. Well, they’ve got a $180 billion locally raised funding dedicated to putting that rail system back in, and they are 40 percent toward doing that. They got the funding committed through a sales tax increase.

And the same is happening in Miami to a lesser extent as far as the rail transit. But both metros are putting the rail transit back in serving the rail-oriented walkable urban towns, such as in Los Angeles, Pasadena, Glendale, Santa Monica, Long Beach, and in Miami it’s West Palm Beach, Ft. Lauderdale and Coral Gables. They are putting the rail transit back in to serve the very towns that were originally laid out as walkable urban-suburban towns, and of course, their downtowns are exploding as well in both cases. Nobody would have forecast in 1990 that Los Angeles would put back their rail system and that the city that was best known for drivable suburban development for the last 60 to 70 years is becoming one of the most walkable urban rail-transit-served places in the country.

What puts Boston at the top of the Future Growth Index?

This is the first time we have been able to call the end of sprawl in Metro Boston for office, retail and multifamily. Ninety-nine percent of all net absorption in all three categories in this real estate cycle went to walkable urban places. Boston’s 50 walkable urban places are 1.2 percent of total land but 99 percent of absorption. Walkable urban place market share is growing 6.2 times faster than its market share in 2010. And the rental rate premium is 83 percent higher in the walkable urban places than in the business parks and regional malls.

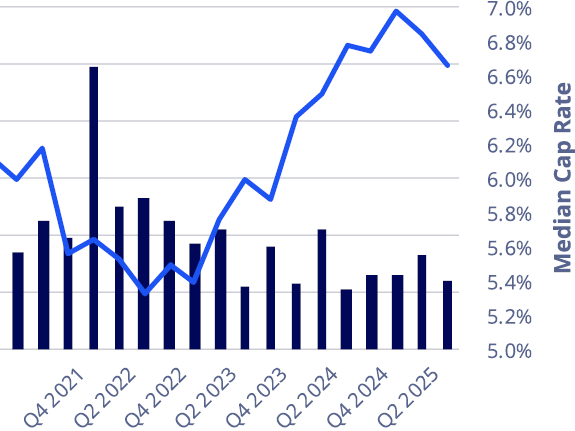

And that is just the rental rates we have found that there is a cap rate premium. Walkable urban product has a 30–50 percent cap rate premium. The cap rates for walkable urban product are between 3 and 5 percent—I never thought I’d see anything less than 6 percent cap rates in my entire career—while drivable suburban cap rates are in the 5, 6, 7 percent range. So that 83 percent rent premium compounds when you apply the cap rate premium. It will be a 110-120 percent valuation premium on a valuation per square foot basis.

You also looked at social equity performance. Why is that important?

We have this major issue going on in this country about the social equity of these places—gentrification pushback on income inequality. The unusual thing that we have found is the most walkable urban places are also the most socially equitable places—even though they have these huge price premiums. It’s counterintuitive.

And the reason for it is, yes, the rent is too damn high, but the rent is too damn high in most of these metropolitan areas. Low-income households—and we only looked at 80 percent of Area Median Income households—should not be spending more than 30 percent of their income on housing. In almost every region of the country, they are spending more than 30 percent, and certainly in the walkable urban places with these big price premiums they are spending more than that. But when you look at the transportation costs of these low-income households—and transportation is the second-highest category of household spending—the low-income households are spending about half of the household budget on transportation. Yes, they are spending too much on housing, and we need an aggressive affordable housing program in our metro areas. But when they are in a walkable urban condition, they have lots of other options, and they do not have to have a fleet of cars to participate in society.

How about the difference in GDP between walkable urban places and drivable suburban places?

The final thing is that in the most walkable urban metros the GDP per capita as a region is 52 percent higher than the least walkable urban metros, such as Tampa, Orlando and Phoenix. That is a huge gap in GDP per capita. That is the gap in Europe between Germany and Portugal. A high-flying Germany vs. a relatively much lower-income Portugal. It is almost a first-world and second-world gap in GDP per capita. You can’t say that walkable urban creates it, but there is logic to it because the knowledge economy wants to be in walkable urban places.

You must be logged in to post a comment.