Retail Scuffles, But All Is Not Lost

News of retail bankruptcies and store closings might be making the most headlines, but retailers and retail owners that can adapt to changing consumer preferences and compete with the rise of e-commerce can still prevail, argues Yardi Matrix Analyst Justin Dean.

By Justin Dean, Real Estate Market Analyst, Yardi Matrix

One topic being frequently debated within and outside of the real estate industry is if the reports of retail’s death have been exaggerated. While changing consumer taste and the growth of e-commerce will like cause retail chains and property owners to experience their fair share of pain in the coming years, the outlook for retail is much more muddled than the prevailing doom and gloom sentiment hovering over the industry at the moment.

One topic being frequently debated within and outside of the real estate industry is if the reports of retail’s death have been exaggerated. While changing consumer taste and the growth of e-commerce will like cause retail chains and property owners to experience their fair share of pain in the coming years, the outlook for retail is much more muddled than the prevailing doom and gloom sentiment hovering over the industry at the moment.

Pessimism surrounding retail is not entirely unfounded, however, as a confluence of factors looks to be accelerating the slowdown of traditional retail chains in 2017. Retail bankruptcies are on a record pace so far this year, sitting at a level that has already surpassed all of 2016. Headlines emphasizing these failures and high-profile withdrawals, like Berkshire Hathaway selling off $900 million of Walmart stock, supply an ostensibly gloomier outlook for retail.

Retail employment is also the only sector that has been consistently losing workers so far this year. These developments could lead one to believe we are heading down a one-way path to a predominantly e-commerce world, where brick-and-mortar stores become a quaint reminder of times long past. Yet many of the failings of traditional retail chains will create new opportunities for retail spaces to be creative in reinventing themselves, which is necessary to survive today’s changing retail environment.

Shopping malls struggle

Although some major retailers have so far avoided bankruptcy, several appear to be on life-support, closing numerous stores to keep their heads above water. Department stores are struggling the most, with big-name outlets such as Sears, Macy’s, JC Penny, and Nordstrom all struggling to varying degrees. Several of these department stores were long-standing anchor-tenants in shopping malls. Their closings have hastened the downfall of malls, the once-proud monuments to American consumerism.

While e-commerce is somewhat responsible for the poor performance of malls, offering more options at a lower price than the stores that traditionally lined malls, other factors are also at play. For one, teenagers seem to be less enamored with malls than they once were. Once a popular teen hangout, malls now must compete with the internet and a plethora of options available to teens for how to spend their time and money.

The shrinking teenage labor force could also have a hand in this trend, although it is difficult to gauge the magnitude of such an effect. Since 2000, total employment for those aged 16 to 19 fell 30 percent, a loss of 2.2 million teenage workers. While the vast majority of the jobs teenagers hold are at or near minimum wage, teenagers also have fewer financial commitments (such as rent, insurance and car payments) than other workers, making them a prime target for retailers.

The most prominent factor playing a role in the decline of the shopping mall, however, is simply that too many of them were built in the first place.

In an attempt to stimulate investment, Congress changed the corporate tax laws in 1954, replacing straight-line depreciation with accelerated for capital investments. This, according to urban historian Thomas W. Hanchett, “transformed real-estate development into a lucrative ‘tax shelter.’” Because this change in tax code did not apply to existing structures and also coincided with the period in American history when people were fleeing the city centers for life in the suburbs, shopping centers quickly became an attractive property type. As real estate values soared during the next few decades, astute investors were able to “build a structure, claim ‘losses’ for several years while enjoying tax-free income, then sell the project for more than they had originally invested.”

By the time Congress returned the tax code to straight-line depreciation in the 1980s, shopping centers’ dominance over retail was complete. It would be two decades before shopping centers began to show signs of weakness.

Experience rather than goods

Despite these challenges, Class A malls seem to be thriving in the current retail environment. While some believe this is indicative of the increasing wealth and income inequality in the United States, these luxury malls do have something in common with the other well-performing types of malls: They offer experiences. Outside of Class A malls, the best performing are those that contain services such as movie theatres and full-service restaurants.

Experience is a word on the forefront of every interested party’s mind in the retail industry at the moment. In a world with seemingly limitless entertainment options, e-commerce isn’t the only source of competition for the foot traffic shopping centers depend upon. People have fundamentally changed the way they choose to spend both their free time and income in the last two decades. It’s up to retail spaces to adapt.

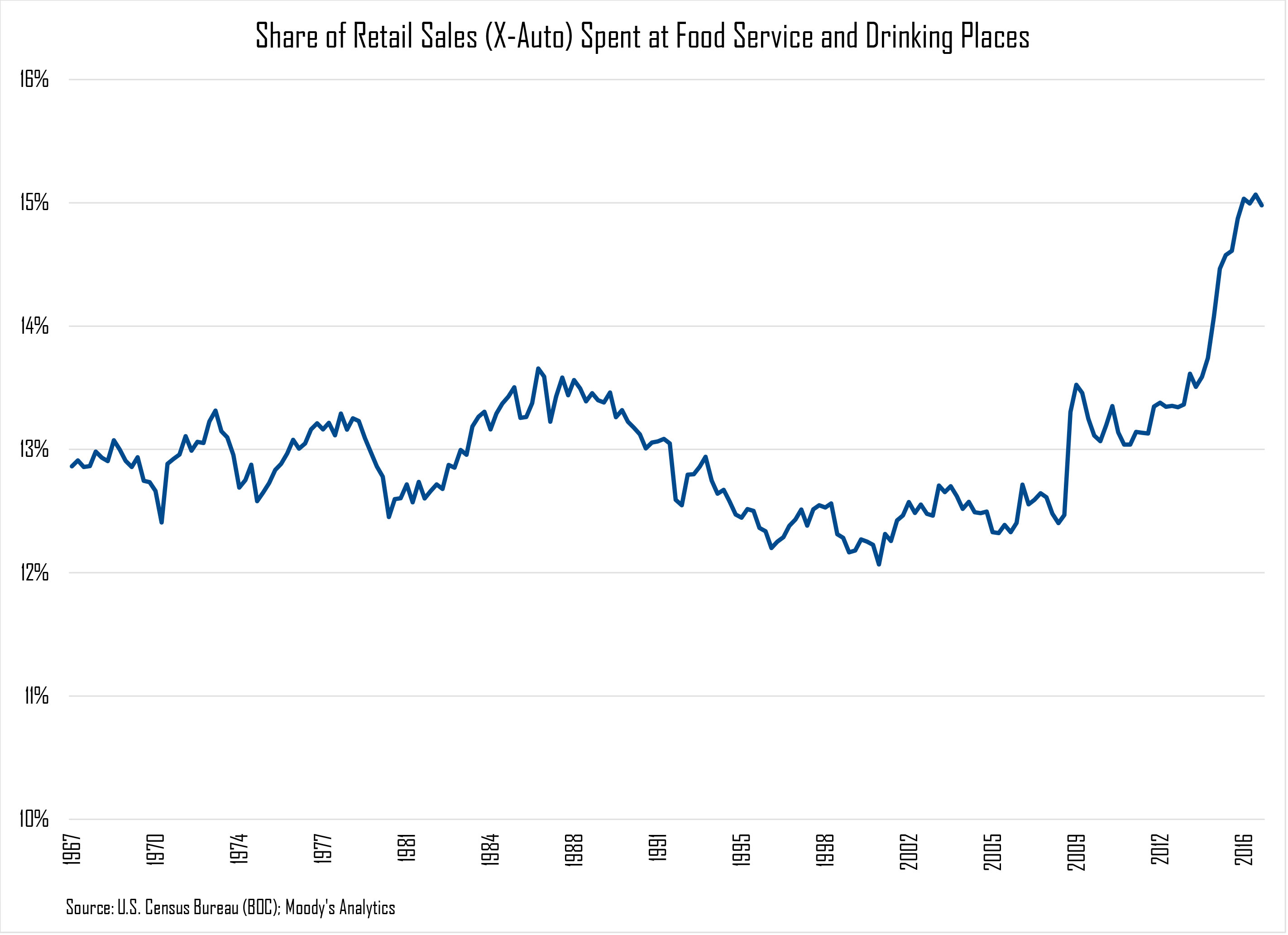

Consumer spending has shifted more toward experiences than objects. According to the Census Bureau, traditional retailers have lost share to two key competitors. The obvious one is e-commerce, which has increased from 6.9 percent of all retail sales, excluding auto, at the turn of the century to 13.1 percent currently. The second, which is less apparent, is that people spend much more of their money eating out than they once did. Spending at food service and drinking locations stood at 13.5 percent in the first quarter of 2014, but increased to 15.1 percent by the end of 2016. An increase of 160 basis points in restaurants’ share of retail spending may seem insignificant on the surface, but it reflects the larger shift in consumer behavior. Going back to when the Bureau began tracking these numbers in the late 1960s, the percent of all retail spending at food service and drinking locations was bounded between 12.1 and 13.7 percent before 2014. The current share of spending is unprecedented.

Spending more on services than goods, on the other hand, is actually the continuation of a trend dating back to the 1950s. As a percentage of GDP, money spent on goods has been in a long decline, from 40 percent at the beginning of 1950 to 22 percent today. It switched places with spending on services in 1969, which stood at 25 percent of GDP in 1950 but is now 47 percent. The decline in goods spending is entirely driven by the drop in spending on non-durable goods, which was 30 percent of GDP in 1950 but accounts for only 15 percent currently. Spending on durable goods has stayed more or less flat as a percent of GDP, staying in the range of 7 to 10 percent during the last six decades.

Hope for the future

We can likely expect shopping centers offering an experience beyond just shops and a food court to thrive where others fail. Outdoor malls that include family-friendly events, patio seating for restaurants, and a balance of shops and entertainment can flourish in this atmosphere, though weather in some areas may be a mitigating factor. Retail chains will need to be more aggressive in their response to these changing tastes. Shopping centers with high vacancies will have to be creative in the coming years, reinventing spaces anchored around restaurants, fitness centers and entertainment instead of large department stores.

Off-price and discount retailers are prospering in this climate, driven by price points that are less vulnerable to e-commerce competition. Some of the fastest-growing chains in 2017 are dollar stores, with at least 1,500 total stores expected to open in 2017. Likewise, Ross (roughly 90 stores by the end of the year) and H&M (430 stores) offer clothing at a price point that is currently insulated from internet competition, compounded by the fact that clothing is still one area consumers like to see the product in person before purchasing.

Online retailers may also offer some hope for the retail industry. Amazon and Warby Parker will open brick and mortar locations in select markets this year. If these endeavors prove to be successful, then many other online brands may follow suit, looking to supplement their online service with physical locations. While it is too early to say if this scenario will play out, the creative destruction of traditional retailers may not be as harmful to the retail real estate industry as initially thought if it does come to fruition.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons user Mike Gonzalez

You must be logged in to post a comment.