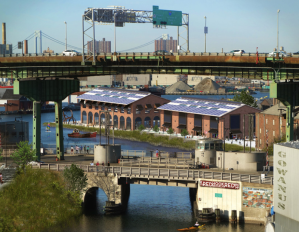

New Life at the Brooklyn Waterfront

A deep dive into the innovative projects that are making this district thrive again.

The Brooklyn waterfront has undergone dramatic changes in recent years, spearheaded by a 2005 rezoning and an increasing number of public-private initiatives. The borough’s office pipeline is growing, while its self storage and industrial sectors continue to perform well.

For many years, the waterfront was largely inaccessible to the general public. Warehouses, dock facilities, boatyards and maintenance yards cut neighborhoods off from access to the waterfront. But recently, the area gained investor attention.

“While maintaining some industrial uses of the waterfront is vital to the city’s economic base, shifts in macroeconomic trends and changes to shipping, manufacturing and industry have ushered in transformative change in the use of the waterfront in many areas of the city,” Marc Gordon, partner at New York-based architecture firm Spacesmith, told Commercial Property Executive.

READ ALSO: Has the Pandemic Changed NYC’s Public Realm Forever?

City planners have been striving to activate former commercial and industrial sites for community use through public parks, recreational facilities, light industry and private residential development. The Brooklyn Navy Yard, Bush Terminal and Brooklyn Army Terminal—which formerly housed military, rail and warehouse facilities—were returned to New York City and developed as hubs of modern, light-industrial businesses, as well as incubators for workforce innovation.

Donald Clinton, partner at architecture firm Cooper Robertson, believes development was slow to start because these waterfronts were essentially abandoned for a long time. There was very little public access—if any—and especially the Williamsburg and Greenpoint areas were cut off from water. Additionally, unlike in Manhattan where the city or the state owns much of the waterfront land, in North Brooklyn private landowners hold most of these parcels.

Projecting changes

Clinton views Brooklyn’s present waterfront greenway path as a huge achievement. Over the years, Cooper Robertson has spearheaded several projects along the Brooklyn waterfront, spanning from Red Hook to Greenpoint. The company was also involved in the very early stages of redevelopment planning for the site of the former sugar refinery, now home to the popular Domino Park and a large mixed-use development scheme.

Interestingly, the Domino Sugar site was not included in the 2005 rezoning plan that transformed North Brooklyn—but it has now become one of the most successful redevelopments in Brooklyn’s trendy Dumbo neighborhood.

At the beginning of the 2000s, Cooper Robertson also worked with the owner of the Austin Nichols warehouse site in Williamsburg to generate concepts for how the historic warehouse structure and the adjacent property could be developed as part of the rezoning. Clinton called it an exciting process because the city actively engaged with all the waterfront landowners to encourage smart development and the inclusion of affordable housing, along with public benefits such as access to the waterfront at every site.

Now, Cooper Robertson is engaged in planning and design work for a multibuilding mixed-use development in Greenpoint, on a site north of the Bushwick Inlet. The shape of the site offers good opportunities to enhance public access and extend the street grid in creative ways.

“There’s a new cultural locus in New York that didn’t exist before, and a whole generation of young renters and buyers has been inspired to go to Brooklyn. … And there’s so much potential still to be realized,” Clinton said.

In its mission to reconnect the citizens of Brooklyn to their waterfront, Brooklyn Bridge Park Development Corp. replaced abandoned piers and transformed parking lots and storage sheds into sports-friendly locations. BBP even relocated its administrative offices from Manhattan to an existing disused building that was renovated and converted by architecture firm Spacesmith. The changes made to the Brooklyn Bridge Park Offices activated the corner of Joralemon and Furman Street, and functioned as the gateway to the southern end of the popular Brooklyn Bridge Park.

CetraRuddy has also worked on numerous Brooklyn waterfront projects, ranging from the residential conversion of former warehouses in Red Hook to the design of new, large-scale, mixed-use developments in North Brooklyn.

One of CetraRuddy’s projects involves a three-building complex at 77 Commercial St. in Greenpoint, dubbed Waterview at Greenpoint. The property will sit on one of the largest undeveloped parcels along the western portion of Newtown Creek. Plans call for more than 700 mixed-income residential units, as well as commercial space and several acres of parkland. When combined with the adjacent city-owned land, the finished project will add more than 600 feet of walkway to the existing waterfront esplanade.

John Cetra, Brooklyn resident and co-founding principal at CetraRuddy, believes the redevelopment of North Brooklyn’s waterfront has brought thousands of people to the Williamsburg and Greenpoint neighborhoods. “These residents support the commercial strips such as Manhattan Avenue, which has helped existing businesses survive and encouraged new businesses to open,” Cetra mentioned.

Former challenges bring change

One of the main challenges arising from waterfront development is the waterfront itself, according to Cetra. “We’ve seen how vulnerable these sites are to flooding and storm surges following events such as Superstorm Sandy. As a result, any building on the Brooklyn waterfront needs to be elevated out of the flood plain. This is critical for the longevity of the buildings,” he noted.

By elevating and reinforcing the waterfront zones, projects in this area represent an investment that also doubles as preservation. And while waterfront development and former industrial uses can prove quite challenging, Clinton points out that the specifics of North Brooklyn’s new zoning could also represent a development hurdle.

READ ALSO: Staten Island’s Industrial Past Shapes Its Future

However, considering the large number of underutilized waterfront areas in Brooklyn, there will be continued interest from developers, community groups and urban planners to utilize the waterfront to its best and highest use.

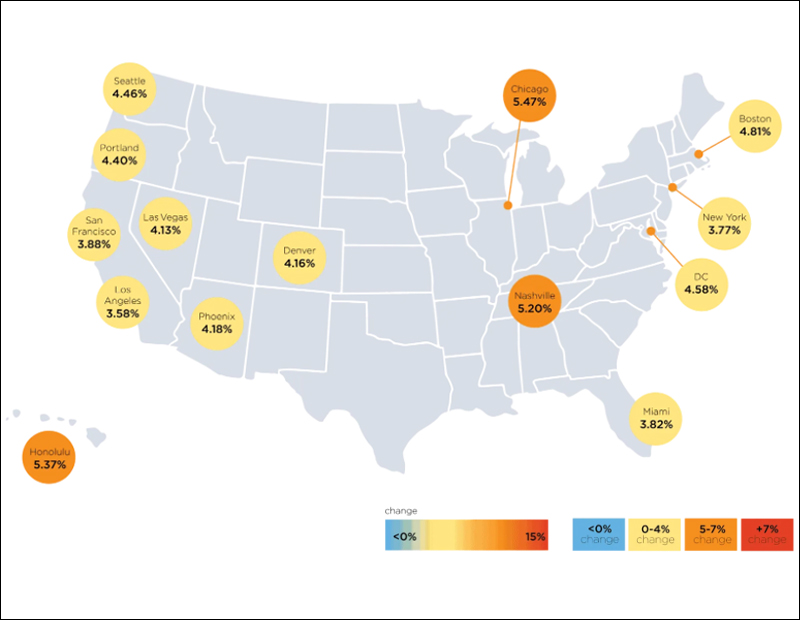

According to Gordon, New York has rediscovered that it is a waterfront city with 520 miles of coastline—longer than the coastlines of Miami, Boston, Los Angeles and San Francisco combined. Intelligent development, community and neighborhood needs, flood protection and mitigation, erosion protection, environmental protection, sustainability and equity are just a few issues that factor into continued rezoning, reuse and development of the city’s waterfront.

What’s next?

Many sites are already rezoned to accommodate development, even if they’re still occupied by vestiges of the industrial past. Clinton noted that the parks are coming online piece by piece, but because it’s such a unique development model with each private landowner contributing to the public open space network, this is a slower process than it would be on city-owned land.

Recommendations for Red Hook Resilient Commercial and Industrial District. Image courtesy of Cooper Robertson

The city can help spur this growth by continuing to invest in better infrastructure, like it did with The East River Ferry, Clinton said. Cetra agrees that new development should be accompanied by improvements to the surrounding infrastructure, including utilities, transit and also city services such as sanitation, schools and fire protection.

There’s been a lot of talk about potential development in the Red Hook area, for example. “However, major improvements including better sewer lines, water lines, power lines and transportation networks would be necessary to support large-scale development,” Cetra said. And large projects on the Brooklyn waterfront will come with the right kinds of incentives.

Furthermore, elected officials and the development community also need to recognize that New Yorkers will never have enough open space in the city. More public space should always be the payback for some of the incentives that local government offers. Similarly, incentives can also spur affordable housing development. If these waterfront neighborhoods do not incorporate a significant number of affordable housing units, isolated upper-middle-class enclaves will appear as a result.

Architects agree that although it’s going to take time, the successes on the Brooklyn waterfront will open the path for similar development across the borough, very much like the transformation in the Bronx with the Hunts Point and Mott Haven waterfronts, where areas that were completely vacant are now growing again.

You must be logged in to post a comment.