Ripe for Renewal: How Redevelopment Efforts Are Reshaping the Urban Core

Conversations about Baby Boomers, Generation X and Millennials often focus on their differences, but millions of people in each cohort share something crucial: an inclination to seek out dynamic urban environments.

By Sanyu Kyeyune

Upon completion, Port Covington will add as much as 18 million square feet of mixed-use development and 40 acres of open space and parks to South Baltimore’s underused waterfont. Image courtesy of Sagamore Development

Conversations about Baby Boomers, Generation X and Millennials often focus on their differences, but millions of people in each cohort share something crucial: an inclination to seek out dynamic urban environments.

Multiple generations “have warmed up to the tradeoffs of urban living because they see the advantages of easy transit access and vibrant nightlife,” said Jess Zimbabwe, founding director of the National League of Cities’ Rose Center for Public Leadership in Land Use. In response, investors and developers are revitalizing once-neglected urban infill locations that rank among today’s most ambitious, challenging projects.

On an underused waterfront site in South Baltimore, Sagamore Development is eyeing a 260-acre mixed-use play: Port Covington, an 18 million-square-foot redevelopment that will include 40 acres of parks and open space. Sagamore CEO Mark Weller sums up the mission of the project’s projected 25-year buildout: “To add to a great American city, while being respectful of its past and looking to the future.”

Sagamore aims to attract businesses to Baltimore’s comparatively low-cost operating environment, and one marquee tenant is already on board: Under Armour, which will take up residence in a 3.9 million-square-foot corporate headquarters. In addition, Sagamore is betting that Port Covington will appeal to residents seeking reasonable rents in a lively, centrally located setting.

Obsolete industrial properties are favorite candidates for reinvention. During the past four years, Jamestown has completed adaptive reuse redevelopments totaling upward of 12 million square feet, including such landmarks as Ponce City Market, the 2.1 million-square-foot development along Atlanta’s recently redeveloped BeltLine, and Chelsea Market, a trendy 1.2 million-square-foot retail market adjacent to the High Line park in Manhattan. Both opportunities offered “strong historic fabric, a lack of retail amenities, efficient public transportation and alternative green space,” explained Michael Phillips, the firm’s president. The two developments exemplify Jamestown’s strategy of creating transit-oriented, live-work-play spaces that benefit from revitalized infrastructure.

While repurposed industrial properties are in high demand, they also carry their own set of risks. Remediating brownfield sites, such as those that dot Atlanta’s BeltLine, is often costly, as is bringing outdated structures up to code. Jamestown encountered both issues in creating Ponce City Market from a 1926 Sears, Roebuck & Co. distribution facility. Moreover, the firm had to secure rezoning, and in order to incorporate a food hall and beer garden, proposed an amendment to Atlanta’s open container laws.

Cementing partnerships

Rallying stakeholders is another challenge facing large-scale urban revitalization projects.

Rallying stakeholders is another challenge facing large-scale urban revitalization projects.

To meet that goal, Weller is making good on his firm’s commitment to the communities surrounding Port Covington’s future home. An agreement cinched last year with the city of Baltimore and six neighboring communities holds Sagamore accountable for workforce development and hiring initiatives.

That commitment gained a much-needed boost when Goldman Sachs came on board in September as a private equity partner. The $266 million equity commitment, the largest ever by Goldman Sachs’ urban investment group, will help fund the community benefit agreement. But Goldman may not have signed on unless another crucial piece of the financing package had already been in place: $660 million in tax increment financing (TIF) to support infrastructure upgrades, including a light-rail extension, a water taxi fleet expansion and improvements to Interstate 95 and local roadways. Baltimore’s largest such issuance to date, the TIF bonds will be sold to private investors in late 2018.

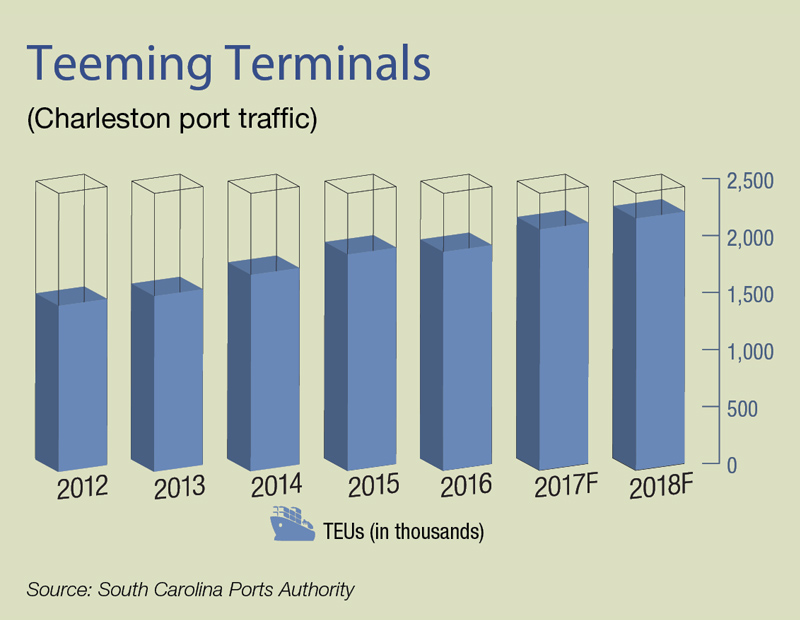

Like Baltimore, Charleston, S.C., is in the midst of a resurgence. Josh Martin, senior advisor to Mayor John Tecklenburg, named quality of life as a primary factor, citing as evidence the seven million visitors drawn by the city last year and more than 250 technology-based companies that have cropped up downtown over the past five years. The manufacturing sector is taking notice: Earlier this year, Mercedes-Benz Vans expanded its local operations, and Volvo announced plans to nearly double investment in an in-progress production facility, underway in nearby Berkeley County, to $1.1 billion.

The Port of Charleston is one of the nation’s busiest, noted Martin, and energized by an influx of college graduates and starter families, the city itself is poised to keep expanding; Charleston granted $1 billion in building permits during the first 10 months of 2016. Now that the city is experiencing broad-based job gains, it’s also racing to upgrade its infrastructure.

Ongoing opportunities

Martin’s growth forecast aligns with findings of ULI’s 2018 Emerging Trends in Real Estate report, which suggests that port and distribution hubs in coastal and southern markets—like Seattle; Portland, Ore.; Miami; and Atlanta—will remain attractive, even in a downturn. Additionally, the report found that high-growth, technology-based industries in those markets account for half of new office jobs.

For Jamestown, whose occupier clients increasingly seek attractive spaces to woo prospective employees, these trends drive the firm to “create demand by delivering product that is dimensionally more accretive to the tenant,” Phillips said, referring to service-based amenities “such as a dry cleaner, nursery school or auto repair shop.” Phillips has found that locating mixed-use developments in amenity-rich environments provides office users with recreational options that make them more productive.

Where talent goes, businesses are likely to follow, Weller asserted. That, in turn, gives cities like “Baltimore, Pittsburgh, Buffalo, N.Y., and Raleigh, N.C., that may have been underserved and where cost of living is low … a competitive advantage over cities like Washington, D.C., Boston and Chicago.”

And as gateway cities become more costly for employers and residents, Phillips believes that occupiers will be willing “to go a few miles further to consider space they wouldn’t otherwise in up-and-coming neighborhoods, as long as it meets their overall objective.”

Originally appearing in the December 2017 issue of CPE.

You must be logged in to post a comment.