Seattle Pilot Seeks Solution to Split Incentives

The city is testing a promising new way to reward property owners for investing in efficiency.

Commercial property operators often face a dilemma about energy efficiency measures. Tenants tend to reap most of the benefits in the form of lower energy bills. That gives little incentive to put capital into upgrades that may primarily benefit their customers or the property’s next owner.

Seattle skyline photo courtesy of Seattle City Light

But a program in Seattle is testing a possible answer. This spring, Seattle City Light, the local public electric utility, will implement the Efficiency as a Service (EEaS) pilot program, which will eventually encompass 30 buildings.

The Metered Energy Efficiency Transaction Structure (MEETS), which is partnering with Seattle City Light, successfully tested the strategy at the Bullitt Center, the landmark seven-year-old green building, reported Rob Harmon, executive director of the MEETS Accelerator Coalition.

To qualify, participating properties must be at least 50,000 square feet in size, and one utility customer must represent more than 90 percent of the building’s electricity use. The utility released a request for project proposals in July 2019; applications for the first 15 participating buildings are due March 31.

The EEaS program aims for a solution to the split incentive, a major barrier to addressing commercial buildings’ energy inefficiencies, said Colm Otten, senior program manager for customer energy solutions at Seattle City Light.

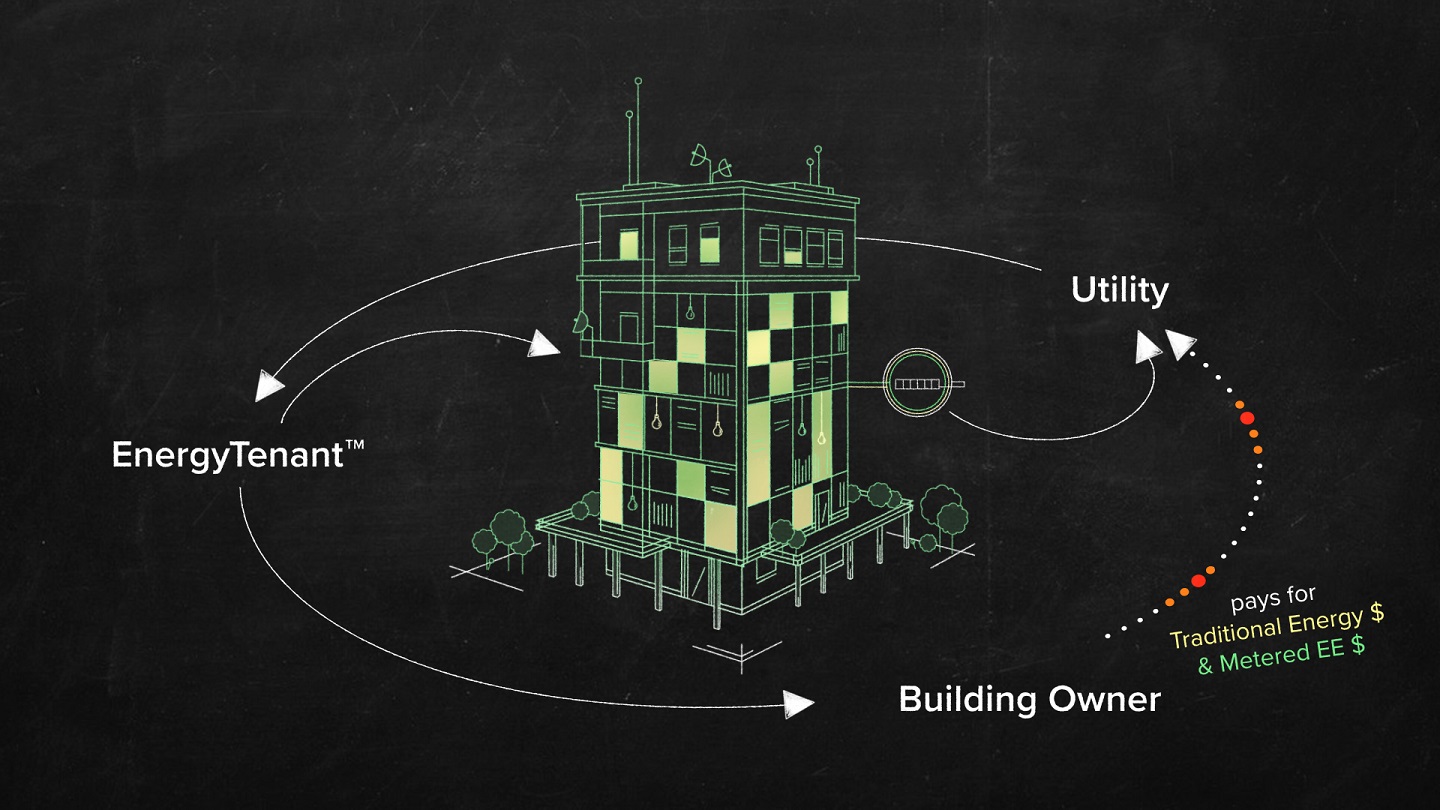

Anchoring the program is the so-called energy tenant. The term refers not to the occupant leasing the property, but to the third-party provider that performs the energy upgrade. After implementing the improvements, the energy tenant can sell the resulting surplus power back to the utility. Like an actual occupant, the energy tenant pays the owner for the privilege of marketing that electricity to the utility.

Owner Benefits

Under MEETS, building improvements are all done under Tenant Improvement Accounting, Harmon explained. Building upgrades immediately belong to the owner. But because there’s no cost to the owner, the improvements are on the balance sheet at zero. “So the leasing of equipment that is normal for traditional energy efficiency upgrades does not exist in MEETS,” he added.

“In a MEETS transaction, the energy tenant is an asset, not a liability, on the building owner’s books. The only liabilities for the building owner are, first, continuing to allow the energy tenant to occupy the space and pay rent, and second, to continue to pay or distribute to the tenants the ongoing energy bills, which will be unchanged.”

How the capital flows in the EEaaS pilot program. Diagram courtesy of MEETS.

MEETS has an immediate and positive impact on net operating income, because the energy tenant pays rent, capital improvements immediately belong to the owner and the owner’s operations and maintenance costs go down. Tenants benefit from a more comfortable and productive building at no additional charge, Harmon explained.

“[Owners’] own operations and maintenance costs decline,” Harmon said. “All they need commit to, is they and their tenants continuing to pay their energy bills . . . The bills will be what they would have been otherwise. In addition, the value and marketability of the building will increase, attracting buyers and renters.”

Other energy-efficiency approaches require utilities to pay incentives to encourage buyers to use fewer of the units they sell. Utilities understandably resist. By contrast, MEETS requires no incentives. Instead, the utility essentially buys an energy resource – efficiency – in units and sells that resource to property owners. “That is just like how utilities treat all other energy,” Harmon said. “It does not result in lost unit sales.”

Virtual power plant

Among the EEaaS program’s energy tenants is Menlo Park, Calif.-based Gridium Alpha. Managing director Ian Guerry defines his company’s role as that of efficiency energy developer. The EE developer signs the power purchase agreement (PPA) with the utility to sell efficiency energy generated at the building, and is involved in every phase from identifying energy conservation measures through the design, engineering, financing and building phases.

The EE developer monitors performance of the equipment over the PPA’s up-to-20-year life, holding the long-term lease with the building called an energy tenancy. It measures the energy efficiency and turns it into a reliable, bankable grid resource. “This is how a commercial building becomes a virtual power plant,” Guerry said.

Gridium Alpha is in discussions with five other utilities in markets outside Seattle to join similar pilot programs. “Utilities and grid operators are beginning to embrace the idea of energy efficiency as a resource,” Guerry said. “We expect this to scale quickly.”

Harmon also envisions growth, reporting interest from Hawaii and New York City. Existing or pending efficiency mandates in several markets call for fixing buildings. “Often absent from those mandates is a mechanism to cost-effectively and profitably upgrade the buildings,” he said. “MEETS is the solution to that problem.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.