SITELAB’s Laura Crescimano on Urban Design That Works for People

Committed to designing for public life, the company’s co-founder & principal shares her vision and strategy.

Laura Crescimano, Co-Founder & Principal, SITELAB Urban Studio. Photo by Todd Johnson, San Francisco Business Times

This Women’s History Month, in celebration of female leaders in the real estate industry, Commercial Property Executive is sharing the voice of several women with stand-out achievements in their field.

Laura Crescimano is the principal of SITELAB urban studio, a design and planning firm currently working on some of the Bay Area’s most ambitious mixed-use projects. Crescimano co-founded SITELAB a decade ago and has been fueling the vision of ecological urbanism that lies at the core of her team’s approach.

“Cities are at their essence a place for shared resources, which is inherently a communal and community act. The work now is to imagine how they can do more for more people, how we can support transformation where greater change is needed to address rising sea levels or historic inequities,” Crescimano told CPE.

SITELAB’s involvement in urban development ranges from massive projects like Pier 70 or 5M, which aim to shift the dynamics of entire neighborhoods, to community-level action. In the interview below, Crescimano talks about what it takes to lead a diverse multidisciplinary team, while holding to the core principle that “we can learn about places best through the people that know them.”

LISTEN TO: CREW Network President: ‘Speak Up for Yourself!’

You co-founded SITELAB 10 years ago. Could you please tell us a bit about how you started this journey and what drove you to where you are now?

Crescimano: I started the firm in 2012 with Evan Rose, after a fateful three-hour coffee in which we realized that we had the same passions about how design and public life intersect, and that we both found ourselves digressing into the politics of space or the function of a street café when we spoke about design.

The vision for SITELAB urban studio grew out of mine and Evan Rose’s mutual interest in recasting urban design as a social practice, beyond simply technical or formal study. We wanted to ask: How can we design our cities and public spaces as places for people—to be inhabited, shaped by use and thus brought to life? We wear a lot of hats and our projects range from strategic and resilience planning to urban design, temporary installations, placemaking and community engagement. When Evan died of cancer in 2015, he left me with the great gift of a platform to continue this work and to chart out a space for a diverse woman-owned firm committed to designing for public life.

What does it take to lead a multidisciplinary team in today’s commercial real estate landscape?

Crescimano: SITELAB was built on collaboration and curiosity, and on a diverse team that questions what is possible. A central tenet is that we can learn about places best through the people that know them. Our team is composed of people from over eight different countries, with a variety of professional backgrounds, building on and enabling diverse perspectives to create equitable places. Because of this, we are regularly able to sit on different sides of the table, maintaining public, private and community-based clients. Working across these sectors, we gain insight into the language, drivers and mechanisms of each.

At SITELAB, we want to redefine what urban development should be in the 21st century. We bring together siloed teams, settle on competing goals, and deliver socially and culturally conscious designs. And we keep learning and asking questions. Our innovation lies in prioritizing a process of co-creation that puts people first. We make complex issues clear so more people can participate in decision making.

As a firm that typically works on large-scale development projects, we like to take the both/and approach to place. We look for the kernels of place that already exist to combine with the new. We combine ecology and urbanism, the pre-planned with room for the organic and unexpected, and development strategies that center around community and connectivity.

What are some of the first things you look at when deciding if a new project is worth it?

Crescimano: We approach new projects with the central principle that cities are and will remain the dynamic core of our society. Every place we work in contains multitudes, so we start with a lot of looking and listening, to understand the physical, cultural, historic and environmental layers. We build from what is—looking for opportunities to connect through literal pathways, and an attitude about the character of a place. We simultaneously dig into the technical side, assessing the possibilities of the site and teasing out scenarios and pros and cons. Our approach is simultaneously creative and pragmatic. Our track record of successful and innovative, development-ready design projects for developers and public clients draws on the lessons learned.

You said that it is important to put people first in design. To what extent is this reflected in San Francisco today, two years into the global health crisis?

Crescimano: Alongside the public health crisis we’re facing, almost every U.S. city is plagued with deeply rooted urban issues including a lack of affordability, opportunity, sustainability, and its response to rising sea levels, efficient transportation, lack of green spaces. The history of urban design and planning as a profession is itself derived from the need to create systems to address health and sanitation where people have gathered into denser communities.

With the ongoing pandemic, green spaces and open urban spaces have never been more vital for communities, especially those disproportionately impacted by COVID-19. By investing in and democratizing our public spaces, we can create a more equitable and accessible public domain.

READ ALSO: San Francisco Market Update—Office Construction Headed Back on Track

In San Francisco specifically, right now, we are partnering with the Downtown Community Benefit District to lead the development of a public realm action plan that will include a new vision for activating vacant ground-floor retail spaces, investing in more public art, increasing accessibility and flexible seating, as well as inclusive community programming. Looking back, the shift to virtual work left local businesses to struggle, office spaces empty and downtowns losing the constant stream of workers.

We’re working to reimagine the future of downtown San Francisco to be a safer, more vibrant and culturally rich area. The public realm is a key part of this, but it can’t do it all. We’re prioritizing the impact design can have, while finding opportunities to be provocateurs about bigger questions and policy opportunities for San Francisco and cities for the next era.

We are similarly bringing this thinking to working with the Port of San Francisco on the Waterfront Resilience Program—looking for how the coastline can adapt to respond to earthquakes, sea level rise and flooding, and be a place of both industry and community for the long term.

One of the most recently completed projects that SITELAB was part of is the mixed-use 5M in San Francisco’s SoMa. What design aspects of the 5M project would you say reflect SITELAB’s core values the best?

Crescimano: The goal of the overall master plan and design for 5M was to integrate the traditionally dense downtown space and the culturally rich, artistic neighborhood that is SoMa. The foundation of the design follows from this, building from the fabric first: foregrounding the unique alleyways of SoMa that connect to a central plaza that is anchored by historic buildings dedicated to arts, retail and nonprofit uses. Large and small, new and old, office and residential intermix with building entries and circulation converging at the plaza. Color and texture in the facades and open space elements signal that this is not your typical downtown.

For us, the fact that all elements are anchored by the Parks at 5M, playful open spaces that support everything from dance performances to daily outdoor lunches, is representative of who we are as a firm. We intentionally designed this space to support a range of community programming and events, including those that will be hosted by arts and cultural nonprofits and other innovators such as CAST, Kultivate Labs, Off the Grid, and the Filipino Cultural District.

The overall design presents a rare opportunity to have multiple acres of land within the heart of a city, to build opportunities for connection, for district-level thinking where the residential, office, open spaces, ground floors and programming can work together and serve the greater neighborhood.

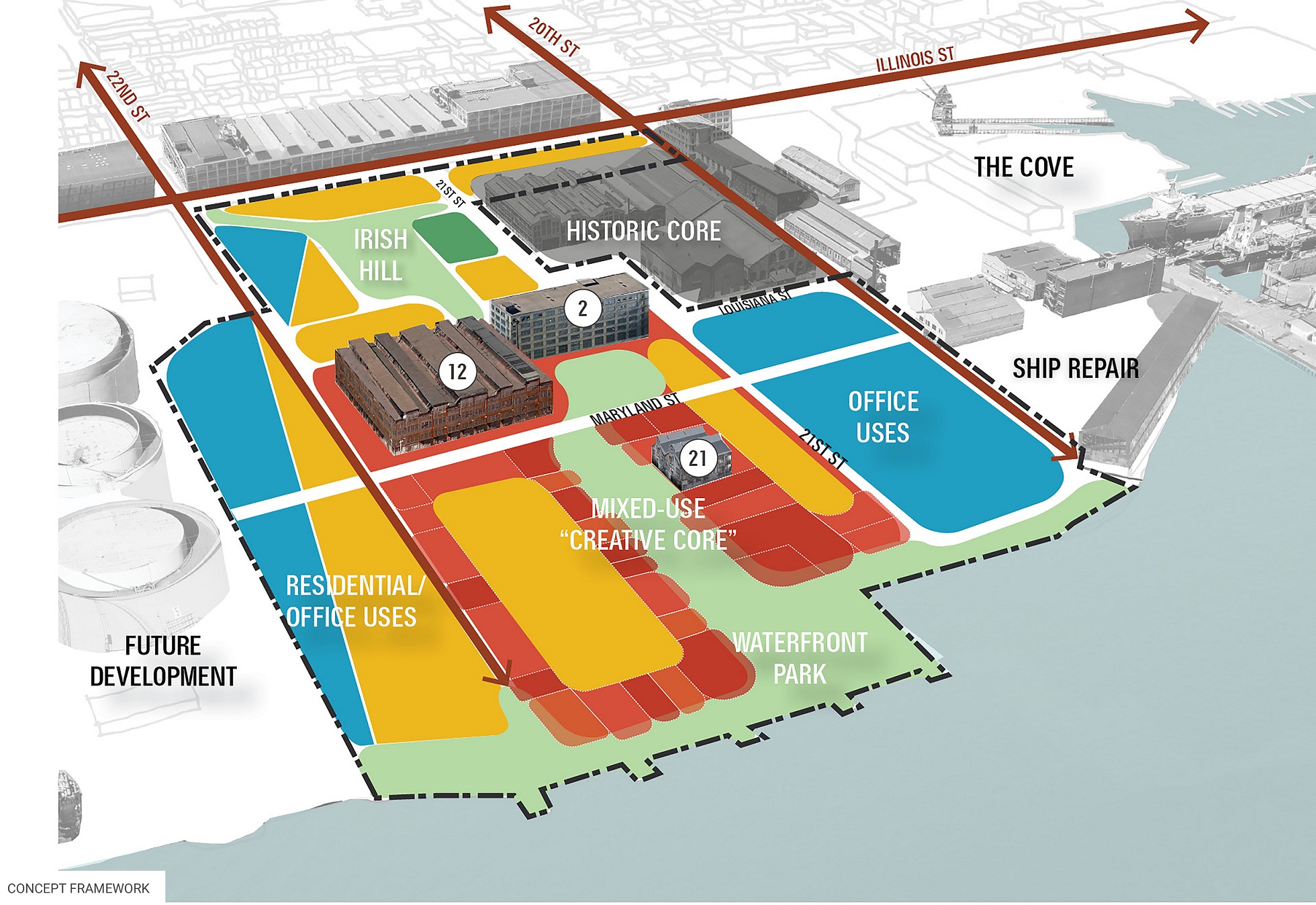

Pier 70 is another massive project that SITELAB is involved in. Please tell us about your work on Pier 70 and what it took to make it happen.

Crescimano: Yes, we’re extremely proud of our leading role for the design of Pier 70. Initially, San Francisco was lined with industrial plots of land with many antiquated buildings from the historic ship-building era. Pier 70 unlocks public access to a new portion of the San Francisco waterfront and an important piece of national industrial history. With the ongoing pandemic, access to open spaces and the power of the waterfront and the vistas it provides cannot be underestimated. Pier 70 will utilize a huge chunk of the high value waterfront to bring in a mixed-use space with housing, office, open space, access to the waterfront, arts and cultural programming, and more.

The project took many years and benefited from strong partnerships between the developer, the neighborhood, the local business owners, artists and artisans, and the design team. The process ranged from in-depth technical studies to creative visioning: How to handle sea level rise and raising a site amidst protecting historic warehouses? How to build millions of square feet of new housing and office space while respecting the character of a place? How to truly connect people to the waterfront?

We worked with City agencies, local residents and stakeholders to create the space from a place of co-collaboration. With deliberate variety and contrasts of scale, the plan creates a rhythm of connected open spaces from neighborhood to historic core to the waterfront. When developing the Pier 70 design guidelines, we created a framework that retains flexibility for future design strategies, incentivizing attention to materiality and craft—features of the historic site and the creative neighborhood of the Dogpatch next door.

Aside from Pier 70, 5M, or Google’s downtown San Jose development, SITELAB is also working on smaller-scale, more community-focused projects. Apart from size, what are some of the key differences between these types of projects and what drives you to pursue them?

Concept image for The Greenhouse Project in San Francisco’s Portola District. Image courtesy of SITELAB

Crescimano: While we are working on some of the Bay Area’s largest development projects, we also prioritize time to work directly with community groups through notable collaborations like the Lava Mae Pop Up Care Villages and The Greenhouse Project, among many others. At SITELAB, we use the same strategies at whichever scale we are working—looking closely, listening, creative problem solving, and finding the opportunity for a shared vision even amidst challenges and constraints.

Sometimes this takes the form of a physical design for a historic block of greenhouses, sometimes it is helping a nonprofit explain the complexities of its work with a clear set of graphics or facilitating a conversation between community stakeholders to see their own both/and to deliver something greater than the sum of its parts. By seeking out opportunities to utilize our skills of community engagement and urban strategy, we look to help our community tackle the big and small problems facing our cities.

I watched a video where you talked about the importance of maintaining people’s connection with nature within the built environment. Do you think San Francisco’s current trajectory is compatible with this view? If so, how?

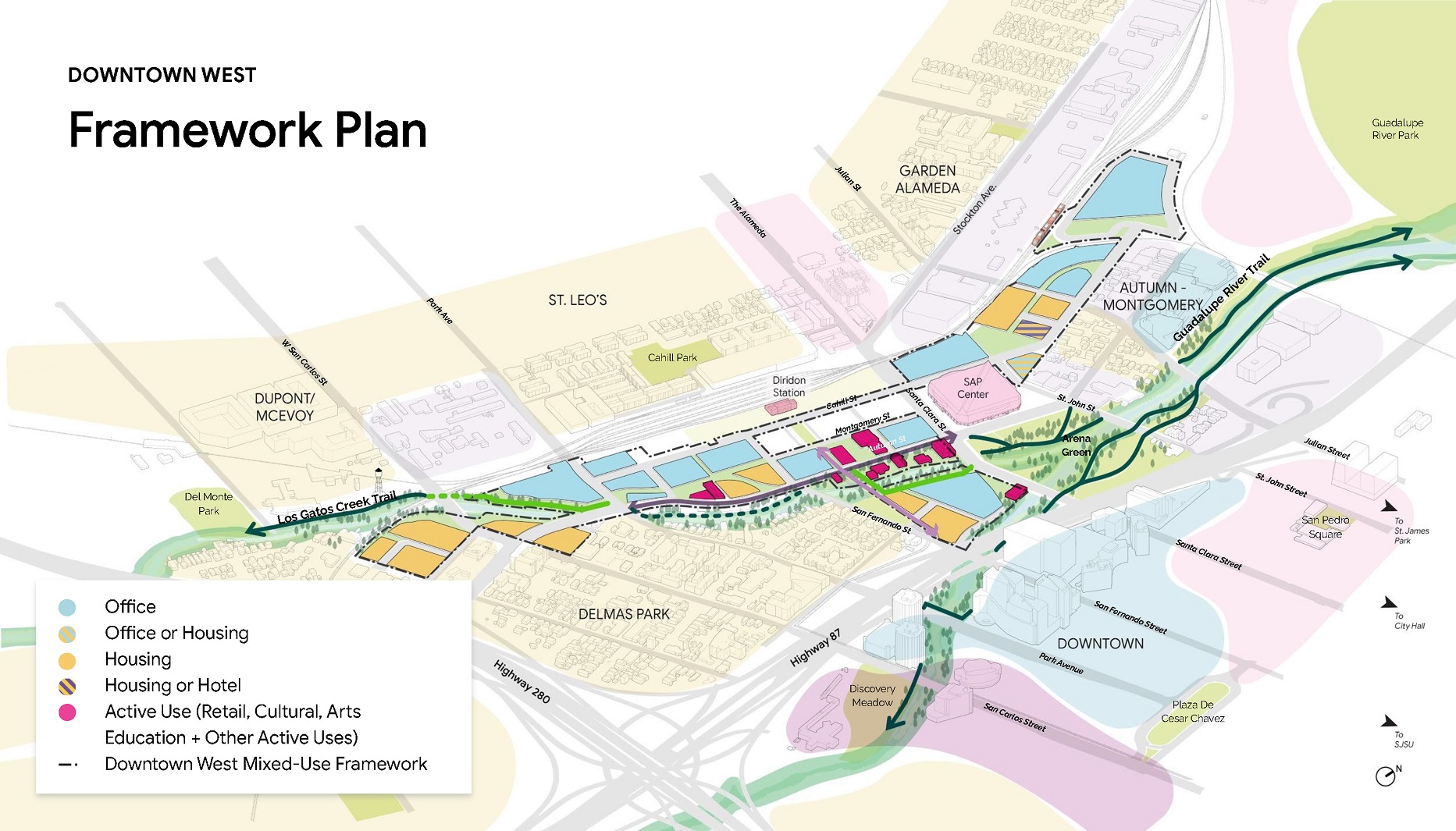

Crescimano: At SITELAB, we’ve called this approach ‘ecological urbanism’, a practice that emphasizes drawing from an area’s ecology to guide urban development and looking for opportunities to thread nature into dense urban areas while also creating density in some places so that we can protect for larger swaths of more robust natural areas in others. This has benefits from mental health to resilience amidst climate change, to maintaining biodiversity. For instance, for the design of Google’s Downtown West, our team worked with ecologists and community advocates to support and improve the creek-side ecology while creating much-needed housing and expanding downtown’s commercial core.

It is also important to note how critical partnerships can be. We can do so much more in collaboration. In most of our recent work, SITELAB has worked with San Francisco Estuary Institute’s Urban Nature Lab. SITELAB focused on development and placemaking and SFEI focused on expanding green infrastructure to support ecological resilience and biodiversity across the Bay Area. It has become clear we can use science-based thinking to create spaces supportive of ecological and placemaking goals and vice versa. We see these opportunities and collaborations happening in San Francisco with renewed power as we have sought out open spaces and the role of greening to support both our mental and physical health, as well as our cities’ resilience.

What would be an indispensable piece of advice you would give to other people who wish to work in urban design and planning today?

Crescimano: I really think building off a both/and approach is key to integrating design and planning into local communities. Anyone looking to work in the industry today can implement this approach in all aspects of their professional life.

Having an open mind and listening to the others around you, including mentors, collaborators, clients and communities, enables more free-flowing creativity within any development. Be willing to have your mind changed. Cities emerge from many, many hands and generations of use and change. If we allow room for ideas and understanding to emerge—in other words, approach with humility—the process as well as any outcomes will serve more.

I have found that projects have the best outcome when the innovation of our firm and the community combine forces to create the best possible plans. And plans are just that—we try to protect the core of a vision, and allow that success is where more people become stewards and make a place their own.

You must be logged in to post a comment.