Stability Encumbers CMBS Market

Forged out of crisis and sharpened during a cycle of frenetic activity, the CMBS market is struggling to adjust to a period of relative calm, observes Yardi Matrix Associate Director of Research Paul Fiorilla.

By Paul Fiorilla

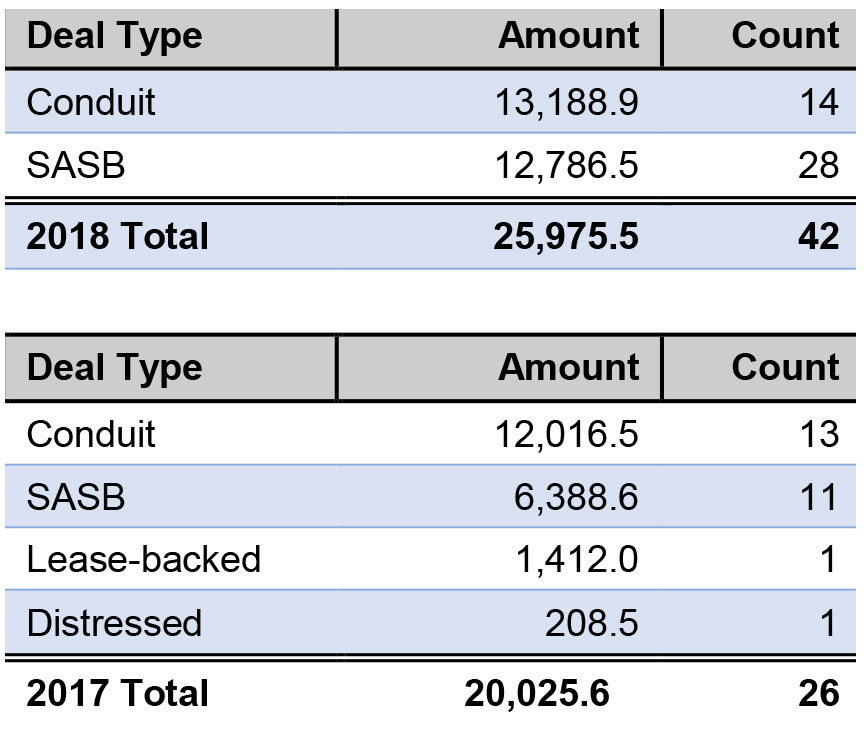

While CMBS volume year-to-date through mid-May hit $26.0 billion, up 30 percent from last year’s issuance for the same period, according to Commercial Mortgage Alert, few analysts expect the market to get near the 2017 full-year volume of $93.3 billion. The market’s bread-and-butter—medium-sized “conduit” loans on properties in secondary and tertiary markets—is shrinking as a share of issuance. Market share is increasingly moving to single-asset single-borrower (SASB) deals, which represent almost half of 2018 deal volume.

While CMBS volume year-to-date through mid-May hit $26.0 billion, up 30 percent from last year’s issuance for the same period, according to Commercial Mortgage Alert, few analysts expect the market to get near the 2017 full-year volume of $93.3 billion. The market’s bread-and-butter—medium-sized “conduit” loans on properties in secondary and tertiary markets—is shrinking as a share of issuance. Market share is increasingly moving to single-asset single-borrower (SASB) deals, which represent almost half of 2018 deal volume.

Challenges come in multiple directions. The small base of triple-A bond investors limits deal size and helps to ensure that loan quality is relatively uniform. There is also growing competition for loans from other sources of debt capital. SASB transactions are not only harder to duplicate but also are often less profitable. Market forces are a headwind, as property refinancings and transaction activity are down in 2018. Plus, the regulatory environment continues to evolve, adding some uncertainty.

While the problems do not compare to those of the post-financial crisis meltdown, the type of freewheeling market in which CMBS thrives is gone and it’s unclear when it will return.

Forged in Fire

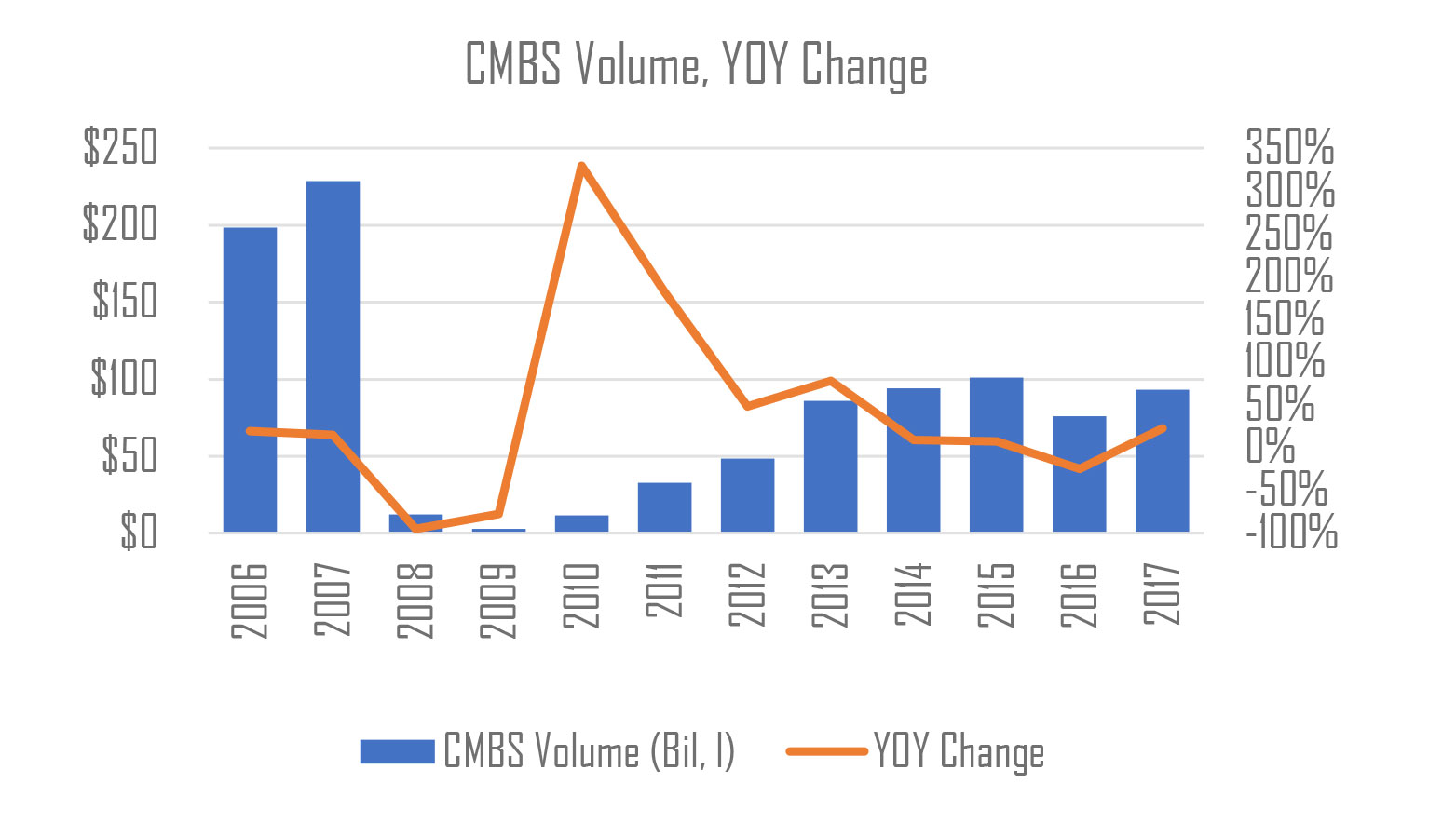

The impetus for CMBS came from the Savings & Loan crisis in the late 1980s, which spawned the idea of banks bundling pools of defaulted loans for sale to investors. When traditional lenders—banks and insurance companies—largely stopped writing commercial mortgages in the early 1990s, investment banks came up with the idea of originating loans and turning them into securities that were sold to investors. After a slow start, the industry surged in the mid-2000s period, peaking at $230 billion of U.S. volume in 2007.

Source: Commercial Mortgage Alert

CMBS not only financed properties—it produced a great deal of structural creativity as it developed. CMBS was constructed in ways that attracted different leverage points, borrower and lender profiles, collateral type, bond structure and more. The idea was to craft loans that would meet the needs of different types of borrowers and investors. Product was available at all parts of the risk spectrum.

That all changed after the financial crisis, when the market was virtually shut down for a few years. What emerged in “CMBS 2.0” was a focus on high-quality loans that wouldn’t keep investors up at night. That made sense in the early part of the recovery when investors had fresh memories of defaults. But eight years into the cycle, despite sterling performance of CMBS 2.0 loans, the freewheeling market has not manifested itself again.

Investors Police Credit Quality

In the run-up to 2007, credit quality often went out the window. Deals with 90 percent total financing—in which CMBS shops securitized the senior tranche while the junior debt was sold in layers to mezzanine investors—were not uncommon. Although the amount of mezzanine debt has crept up slightly over the last few years, loan quality metrics such as loan-to-value ratio, debt yield and debt-service coverage remain much more conservative than during the peak of the cycle. This is especially surprising given the large amount of capital dedicated to commercial real estate that has pushed acquisition yields to all-time lows.

Numerous constraints prevent CMBS from returning to pre-crisis behavior. Arguably the most important is the dearth of investors to buy the triple-A-rated portion of the capital stack, which represents about 70 percent of the securities; Market players say there are barely a dozen large institutions that buy most of the AAA-rated bonds. That limits the size of individual conduit deals to about $1 billion, or about $700 million of AAA bonds per deal.

It also gives senior investors considerable say in how the pools are shaped: if a few pass on buying any particular deal, pricing would slip and the issuer would find itself in a money-losing situation. Senior investors use their influence to demand low leverage and limits on out-of-favor property types (typically 30 percent retail and 20 percent hotel). Issuers say the limits can be counterproductive—for example, a pool weighted more toward strong regional malls might be better collateral than one with more suburban offices—but they have little choice but to acquiesce to the investors’ wishes.

The emphasis on quality extends to other metrics. CMBS has traditionally been the biggest lender on properties in secondary and tertiary markets, or those with minor credit issues. But a pool weighted with loans in smaller markets or weaker tenants/borrowers will get worse pricing, so securitization programs must bid wider spreads for such properties. That makes it harder to win those deals, especially now that regional and community banks are increasingly asserting themselves into commercial lending. Small- and medium-sized banks have doubled their share of the total U.S. commercial mortgage pie to 18 percent in recent years by offering lower coupons and even writing loans with seven- to 10-year maturities to hold on their books, which they rarely did until recently.

Brian Olasov, an executive director of financial services consulting at law firm Carlton Fields, said that CMBS finds itself at a competitive disadvantage. “The two customary advantages that CMBS has long enjoyed—price and proceeds—are dictated by the yield curve and borrower demands for last-dollar leverage. Neither of those is currently favorable to CMBS,” he said.

Single-Borrower Deals Rise As Conduits Fade

While CMBS lost its edge in competing for small- and medium-sized mortgages that wind up in diversified CMBS pools, known as conduit deals, CMBS programs are most competitive today in execution—the ability to close quickly—and in large deals. Banks and insurance companies are less competitive on large loans, which create concentration issues in their portfolios. SASB deals constituted almost half of total volume and two-thirds of deals by number through mid-May, up from about 25 to 30 percent of CMBS issuance in recent years.

CMBS Volume by Deal Type, through May 11 Source: Commercial Mortgage Alert

CMBS can originate and sell large loans efficiently, and securitization programs have longstanding relationships with institutional borrowers. The hitch is that the competition for large loans is strong, and spreads are so tight that profit margins are thin. Securitization programs go along despite the weak profits because SASB deals often involve large borrowers with whom they want to maintain a good relationship.

CMBS will likely struggle for volume if it continues to rely heavily on SASB deals. The wave of 10-year loans originated in 2006-07 has been refinanced, and property sales volume, although healthy, is slipping from recent years as buyers balk at high prices. Plus, there is uncertainly as the market continues to lobby for changes to relax some of the regulations imposed in the wake of the financial crisis.

Competition Leaves Few Niches

By the nature of its design, CMBS will fill in the gaps in the market that are vacated by other types of lenders. That’s difficult at a time such as now when all other lender categories are operating at full capacity. Combined with the low risk tolerance of investors that limits creative originations, that doesn’t leave many niches to be exploited.

While there is nothing wrong with a business model focused on writing and selling generic high-quality loans, CMBS is not most effective or profitable when operating in the same box as its competitors. What’s more, it takes away the structural creativity that is in its DNA and makes it such a valuable part of the commercial mortgage market. Says Olasov,“CMBS has often played the role of alternative lender to life companies, housing agencies and commercial banks. Unfortunately for CMBS market share, other lender types are running record volumes and squeezing out the need for CMBS.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.