The Accelerated Growth of Private Debt Funds

Debt funds are filling the gap left by banks and other regulation-constrained lenders. As dry powder stacks up in a mature cycle, where will fund sponsors place their capital?

By Sanyu Kyeyune

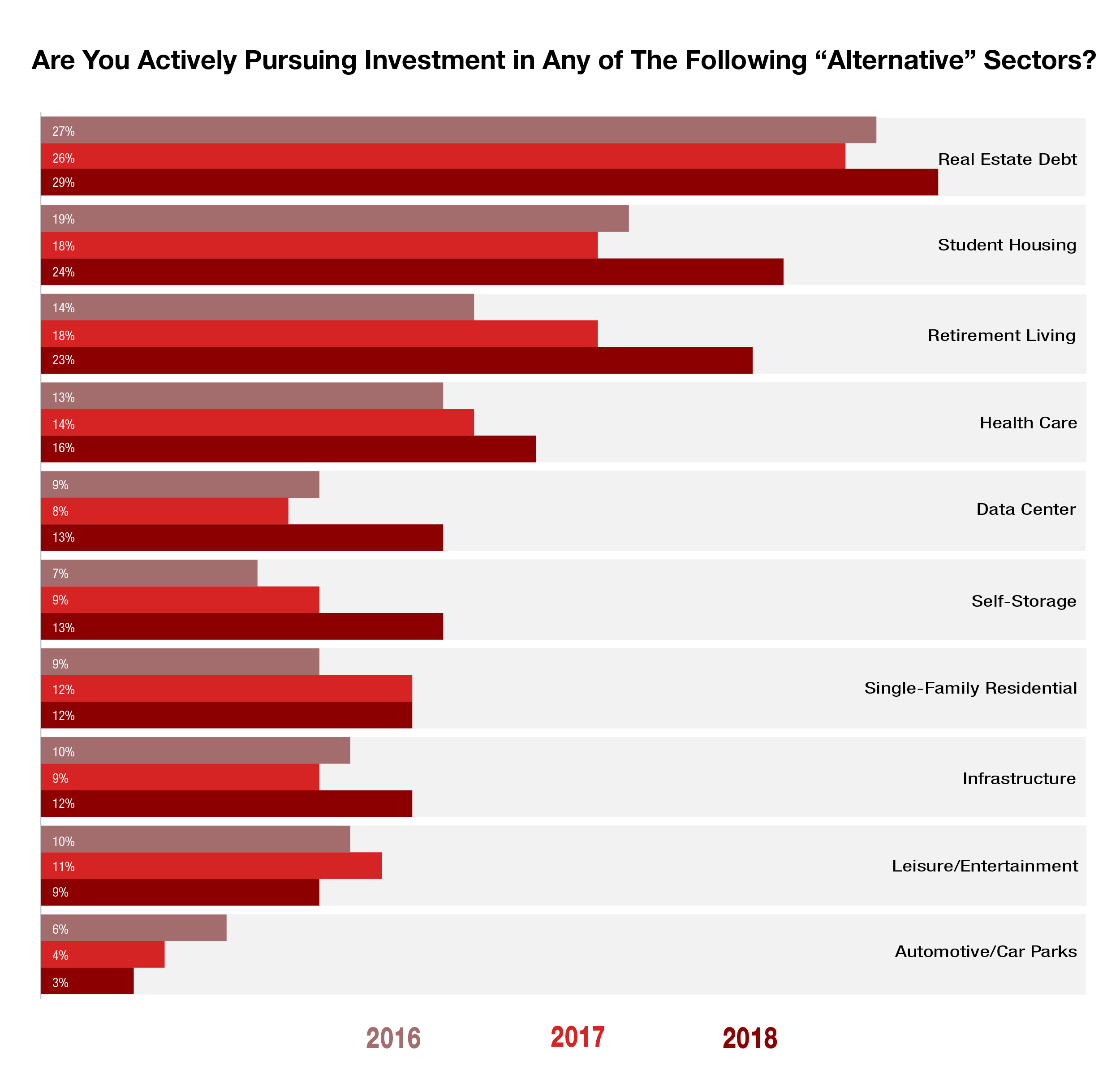

Real estate private debt funds have gained significant momentum in recent years, filling a void created by commercial banks and insurance companies after the 2008 financial crisis. In a market where there are few fixed-income vehicles providing a high current return, these funds have emerged as a darling among institutional investors searching for yield. Serving as a crucial hedge in a mature cycle, the downside protection that debt funds offer has made them a less risky alternative to equity. Furthermore, unlike conventional lenders, these non-traditional capital providers remain unhindered by regulatory hurdles and risk limitations, putting them in an advantageous position to close deals faster with better terms. Add to this their ability to match middle-market borrowers with higher-leverage loans, and it becomes clear why the growth of debt funds shows few signs of slowing.

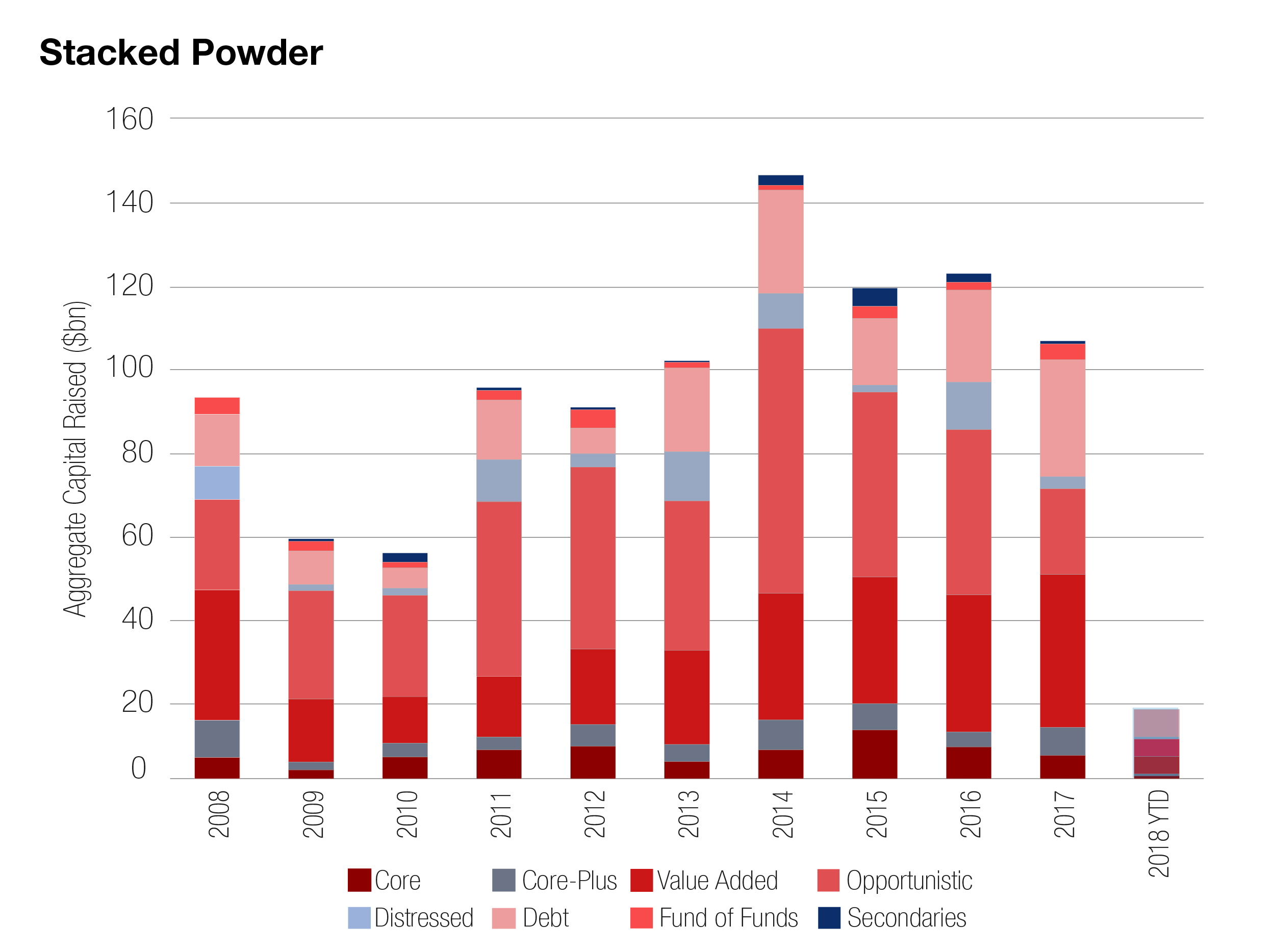

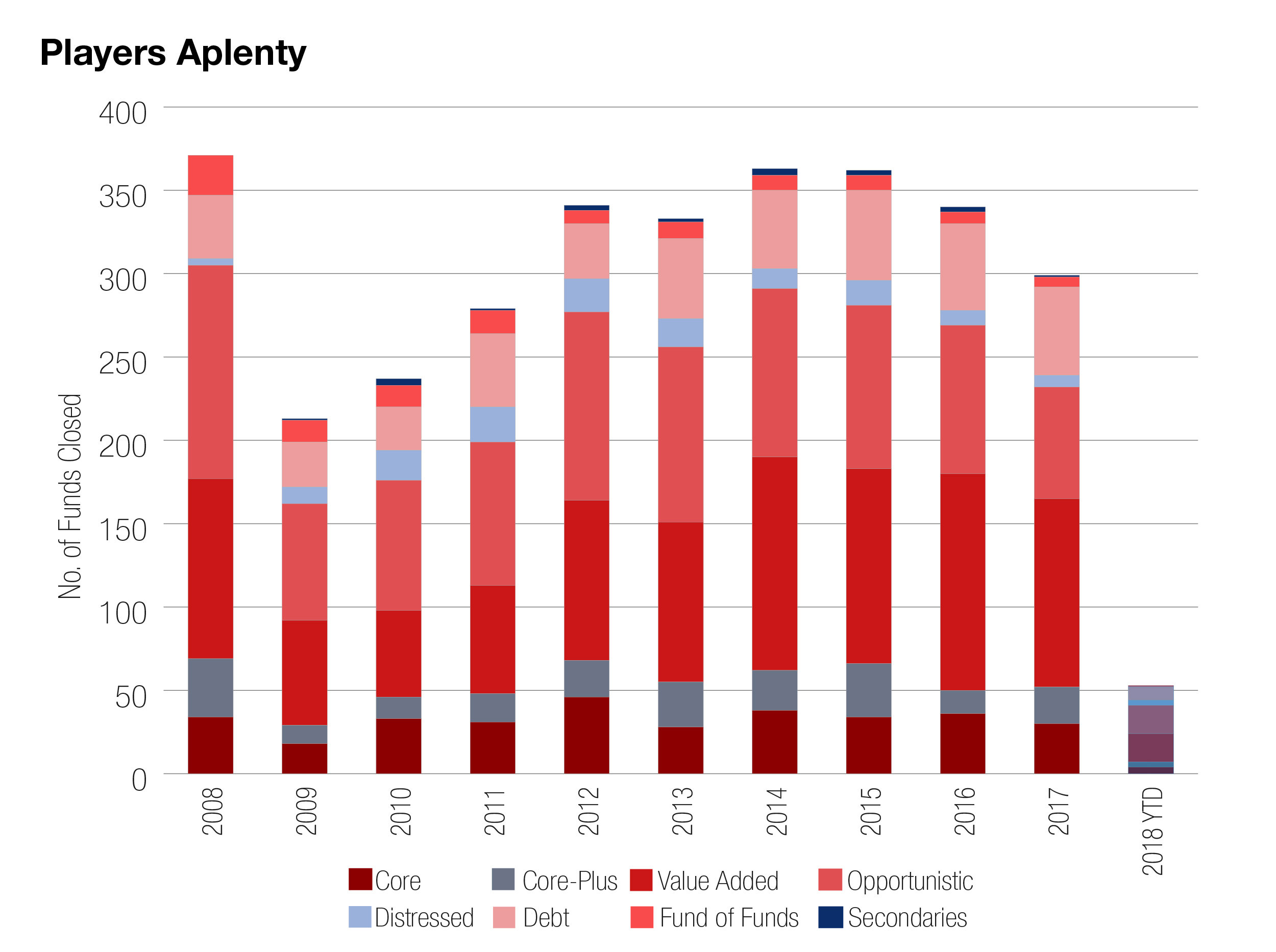

Private real estate debt funds grew substantially in 2017, with 51 vehicles securing $28 billion. According to data provider Preqin, that trend is expected to continue this year: As of March 2018, there were 104 private debt vehicles in the market, targeting an aggregate $39 billion globally. Despite the notable increase in active players and fundraising, debt funds have scarcely scratched the surface of the $3 trillion commercial real estate market, coming in at less than 1 percent of total volume.

Expansion Routes

“Debt funds—especially those targeting higher-yielding mezzanine loans—are finding ample opportunities to place capital, as well as more avenues ahead for (expansion),” asserted David Kessler, managing partner of CohnReznick’s Real Estate Industry practice. Over the past several years, scores of these vehicles have materialized as a more productive alternative to equity investment for a number of reasons.

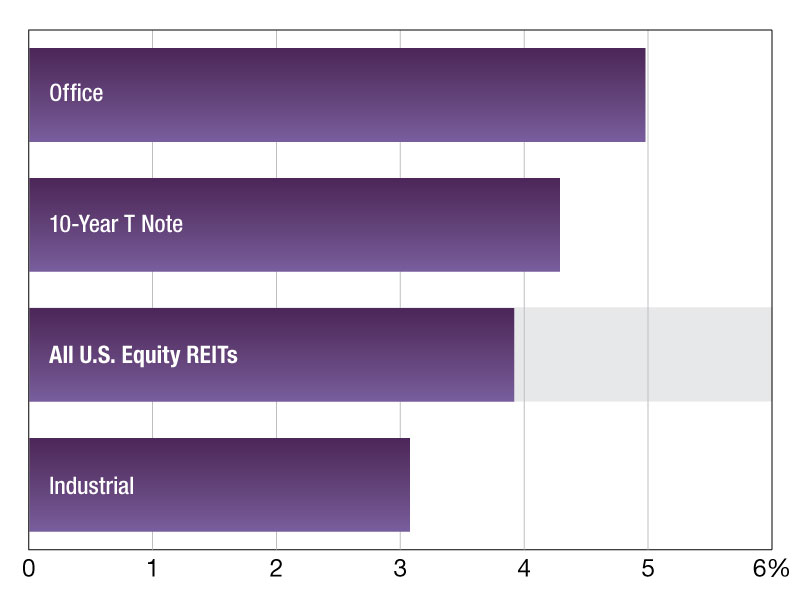

Aggregate Capital Raised by Closed-End Private Real Estate Funds by Primary Strategy.

Source: Preqin

Following the 2008 financial crisis, Wall Street reform catalyzed the rise of debt funds, with Dodd-Frank and other regulatory measures curtailing the availability of commercial real estate debt from banks and other conventional lenders. This tightening provided opportunity for private funds to fill the gap, noted Bruce Batkin, CEO & co-founder of Terra Capital Partners, while a relatively healthy, stable real estate market and low interest rates brewed the perfect storm for further growth.

According to Sadhvi Subramanian, senior vice president of Capital One’s Commercial Real Estate Group, debt funds’ increasing competitiveness with traditional lenders results from their capacity to serve investors looking for higher yields: “Debt funds can finance a vacant, well-located building at higher LTV and lower reserves than banks, whereas large banks are unable to finance the asset as it is not cash flowing.”

The widely held view that the market is approaching its cyclical peak has also driven investor demand for debt funds. “In a more mature cycle, private debt funds can provide a more moderate downside risk profile as compared to equity funds,” said Gary Otten, managing director & head of real estate debt strategies for MetLife Investment Management.

Echoing this view, Mesa West Capital Co-Founder & Principal Jeff Friedman commented that subordinate debt has become a popular way to mitigate late entry into the cycle, especially among international market participants, “partly because it’s an easy spot in the capital stack in which to play. It’s more akin to buying paper than it is to originating loans on a one-off basis, and it provides yield—music to the ears of a non-U.S. investor.”

Hurdles or Opportunities?

Various strategies have emerged within the debt fund space in recent years, with the greatest expansion occurring among vehicles that focus on equity-like risks. Otten names mezzanine, preferred equity and, to some extent, construction loans and construction mezzanine as the best examples, while core debt funds are growing at a more measured pace.

Especially within the mezzanine space, Friedman said, “We’ve been seeing our year-over-year volume increase, mostly because there are fewer banks, and the remaining ones are regulated heavily.”

On the other hand, construction lending has proven challenging. While these loans have historically been a mainstay product of commercial banks, they have been bolstered by recourse and repayment guarantees. Conversely, because debt fund-issued construction loans aren’t necessarily bridled by these covenants, they may experience volatility as the current cycle wears on, Friedman advised.

“By and large, (debt funds) haven’t figured out how to raise money on a profitable basis for construction lending,” Friedman held. “Although debt funds have picked up some of the slack, most sponsors would continue to report that it’s difficult to get construction financing on an economical basis.”

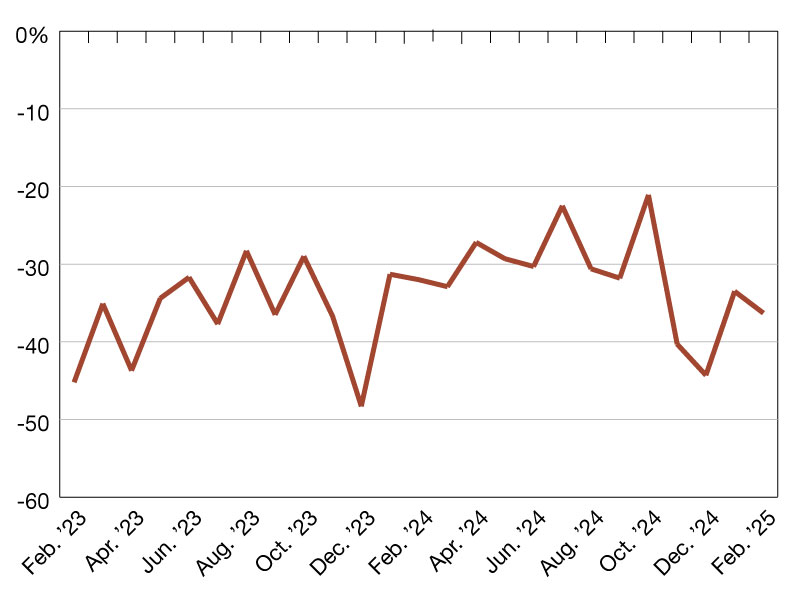

Exacerbating this issue is Libor’s ongoing climb. Although it is due to be phased out in 2021, the rate is currently tied to $200 trillion worth of U.S. dollar-based loans and derivatives, according to data from the Alternative Reference Rates Committee (ARRC). Continued increases to Libor could have the potentially disruptive near-term effects of narrowing credit spreads, magnifying capital costs and making floating-rate debt harder to price. For international capital providers, this trend could also weaken the value proposition of investing in U.S. commercial real estate.

Experience Counts

By contrast, Terra’s Batkin believes construction lending harnesses the most potential, despite it being “an area that requires particular expertise to originate, underwrite and monitor.” Because the number of non-recourse construction lenders is limited, as are non-recourse loan-to-cost proceeds, he sees a wealth of opportunities to provide middle-market borrowers with high-yielding capital for new construction projects.

Still, Batkin maintains a measured forecast for the sector. Consolidation may result from the failure of some funds to deploy capital reserves effectively. Experienced groups, he posits, will thrive while others fall by the wayside. Moreover, Batkin notes, the current cycle shows few warning signs of the overbuilding and overleveraging that led to the subprime mortgage crisis, a factor that contributes to a much more disciplined environment.

“We are flush with capital, and I don’t see that changing as long as we have a good economy,” said Tom Fish, executive managing director & co-head of JLL Capital Markets, Finance. Fish qualified his prognosis by pointing to the looming risk of bank deregulation, which would make it increasingly difficult for debt funds to maintain their niche: “The banks are already trying to undercut with pricing, but the debt funds are still more aggressive with leverage.”

Liquidity poses another potential risk to debt funds, industry veterans say. “The amount of capital raised may exceed the demand for typical debt fund executions at a property level,” Otten observed. “As a result, debt funds are adjusting prices or modifying their loan structures in order to invest dry powder, which ultimately impacts the yield provided to fund investors.”

There are simply too few deals to meet the amount of available equity, concurred Capital One’s Subramanian, and debt funds have been making this task even more difficult for banks in recent years. “Debt funds are being extremely competitive and winning a lot of deals,” she said. “If economic conditions don’t change too much, I think that this will remain the case for the foreseeable future.”

You’ll find more on this topic in the May 2018 issue of CPE.

You must be logged in to post a comment.