Where CRE Meets Health and Social Justice

Panelists at ULI's fall virtual conference discussed how the industry can evolve to better serve the needs of the community, as well as address health and societal challenges.

Over the last few years, the real estate industry has taken a larger interest in the role health, but it’s not enough to only offer health as an amenity. The industry needs to look beyond that viewpoint and work together with communities to be proactive in its approaches to health and well-being through a social-equity lens. On a panel titled “Public Health and Real Estate: Scenarios for 2050” at the Urban Land Institute’s virtual fall conference, industry experts discussed how real estate can evolve to better serve the needs of the community, how to address public health issues, societal challenges and what working together can accomplish in the future.

District Health Consultant Sarah Skenazy moderated the panel, which included RAND’s Vice President & Director of Social and Economic Well-Being Anita Chandra, Lendlease’s Community Partnerships/Development Engagement Manager Quency Phillips, University of Virginia School of Medicine’s Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine and Public Health Research Matthew Trowbridge and USGBC’s Project Manager, Health Research Kelly Worden.

READ ALSO: Emerging Trends 2021: The Changes a Year Can Make

The effects from COVID-19, the increase of racism and police brutality, and the ongoing challenges of climate change have placed health and social inequity at the forefront of tasks to handle in commercial real estate, said Skenazy. “The industry has been reactive instead of proactive and we need to take a look forward and ask ourselves, ‘what could and should the future look like?'”

Social inequities

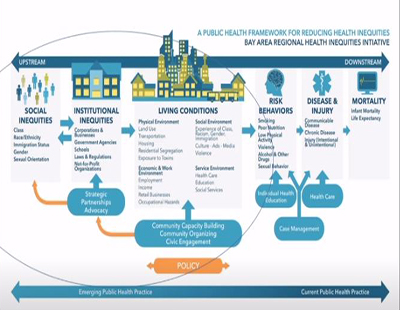

Right now someone’s zip code is more significant in determining their life expectancy than their health history. According to Trowbridge, 20 percent of health outcomes are changed by the variance of the quality of health care someone has, while 80 percent comes from everything else like where someone lives and the behaviors and choices available to them.

“How can public health take what we can do—evaluating, researching—and place that into the hands of someone who can follow through? Developers who can build this project that has intentions on health and envisions a market for this to be a self-sustaining environment,” he said. Factors such as land use, access to public space and fresh air, housing, parks and more, all allow individuals to lead healthy lives, and that comes down to real estate placement.

Real estate decisions can help shape environments and the healthiest and easiest choice is to make a community suited to all incomes, genders and races, explained Skenazy.

The topic of health can essentially be looked at in two ways: Where we were before the coronavirus and where we are now. Before COVID-19, health professionals started to collaborate with other sectors to help raise awareness on the importance of health in real estate, but that was incremental. People often think of health as health care, but instead there needs to be a shift to health inequities for access to a healthy environment. “If the last six months have shown anything, it’s that we’ve had systemic inequities and climate disasters and it has exposed that fact that we’re not doing enough,” said Chandra. “It also shows urgency that we can’t continue to tackle this incrementally.” The coronavirus has proven to be a social, economical and community crisis, not just health.

According to RAND’s 2018 National Survey of Health Attitudes, 37 percent of U.S. adults recognized a strong or very strong influence of social and physical factors on health. However, 28 percent did not consider investment in community health a top priority.

Taking action

On the positive end, the industry has taken some strides to make health a priority. Worden noted the GRESB Health & Well-being Module, the first portfolio level health assessment for real estate practitioners and investors. From 2016 to 2018, a total of 399 real estate funds participated in the module, which represented 5.8 billion square meters (approximately 62 billion square feet) of real estate and more than $1.75 trillion in gross asset value among all property types. The module assesses a real estate company’s internal approach to promoting health for its employees, as well as its external approach to promoting health for tenants and communities through real estate fund management, according to Green Health Partnership.

“Our ability to position health as an investment scale is huge,” said Worden. “Seeing an interest in health and using that within the design and development phase each step of the way.” However, there are some concerning trends she noted. First, the industry needs to ask: Health for whom? Usually developments are focused on the individual health of an occupant, but it’s most important to think about the global health impact and the surrounding community. Second, there is also the overemphasis on office space, such as air quality and social distancing because firms are eager to reopen, but that sector is not the most important one to think about. Third, the best practices that were created among the real estate industry weren’t put in place to think about communities as a whole and that leads to some blind spots, leaving the underprivileged affected.

“We need communities to lead these processes. Intentionality and acknowledgement are very important. That shows steps towards improvement,” said Phillips. “We have an opportunity to reverse engineer practices and policies, social inequities and living conditions. To have a system that thinks about the people.”

Phillips noted to not judge a community by where they were years ago or by a stigma that might be attached, but make the effort to understand that these people can be “advocators not agitators,” and to change the narrative about communities being the problem behind why a project is stalled or stopped.

You must be logged in to post a comment.