The Tricky Task of Office-to-Residential Conversions

Despite gaining traction, the process on the ground involves a big haystack and a handful of needles.

The glut of empty and obsolete office buildings and the severe housing shortage in the U.S. have prompted calls from numerous quarters for widespread office-to-residential conversions—one of the most recent coming from the Los Angeles Times’ editorial board. Meanwhile, states and cities are pushing legislation and policies to incentivize such deals.

From a supply and demand standpoint, the idea makes sense as hybrid work becomes the norm. But true candidates for residential conversion are the exception rather than the rule: Costly design interventions, structural integrity, mechanical system age and performance, floorplate size, zoning regulations, the cost basis and the nature of the neighborhood—any of which can foil a conversion—are just some of the initial variables developers must assess when considering a deal.

READ ALSO: What Hinders Office Space Conversions?

What’s more, some states and cities are demanding that buildings live up to new sustainability measures to fight climate change, suggested Julie Whelan, global head of occupier thought leadership & research consulting with CBRE in Boston. That poses yet another challenge.

“There are some older office buildings that are not going to be able to achieve these new standards, and they are going to have to be dealt with,” she stated. “They’re not always going to have a highest and best use and will just have to be razed.”

At a minimum, developers should plan on spending $500 to $600 per square foot on an office-to-residential conversion, said Richard Jantz, an executive managing director with Cushman & Wakefield in New York. Plus, on a square-foot-basis, the average rental rate for an apartment is about half that for run-of-the-mill office space.

READ ALSO: As Hybrid Work Expands, Coworking Is No Longer the Exception

Hence, not only are developers incurring costs on the conversion, but they also cannot increase their cost basis to generate more revenue from potential residents, he added. That means buying conversion candidates at a discount is paramount. Yet such financial wildcards don’t take into account the tight-fisted credit environment at the moment.

“It seems so simple—you’ve got space that people aren’t using and people who need space to live in, so why not connect the dots?” Jantz said. “But I honestly think office-to-residential conversions are probably the least realistic version of adaptive reuse.”

Needle in a haystack

Gensler worked with PMC Property Group on Franklin Tower Residences, a project that converted the former GlaxoSmithKline headquarters into 360 apartment units and opened in 2019. Image courtesy of Robert Deitchler/Gensler

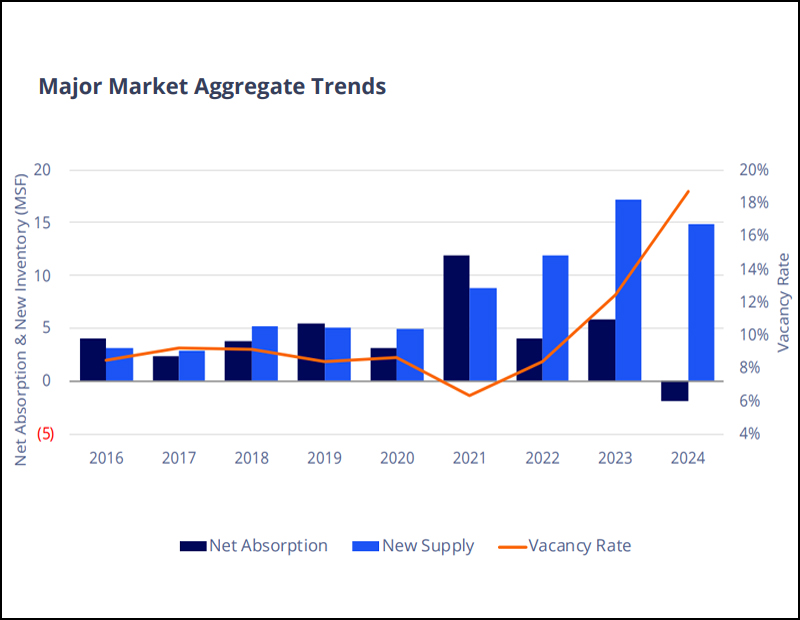

Recent research and tools developed to assess the viability of such projects support that assertion. Looking at completed, in-progress and planned conversions of offices into any alternative use since 2016, CBRE found that 91.1 million square feet has been or would be removed from the market. That’s less than 2 percent of total U.S. office supply, reported Jessica Morin, research director who specializes in office for CBRE’s Americas Research team.

Meanwhile, when assisting the city of Calgary to develop a plan to reuse largely vacant downtown offices in 2018, architecture firm Gensler created a tool to gauge reuse potential by analyzing building and market characteristics, including the state of mechanical, electrical and plumbing systems, the window-to-wall ratio, the size and shape of the floorplates, and surrounding residential rental rates.

READ ALSO: How Vacant Office Spaces Get New Life

The firm found that about three out of 10 buildings in the 43 million-square-foot market had the potential to become apartments, said Kelly Farrell, a principal with Gensler & global leader of its residential practice. “Depending on an owner’s basis in the building, that number may be even lower,” added Farrell.

To help fuel conversions where it makes sense, Calgary is providing grants of $75 per square foot of office space that will become housing. Gensler is now helping U.S. cities formulate similar strategies as empty and underutilized or obsolete buildings contribute to falling downtown property values and diminishing tax revenues, Farrell also mentioned.

“The fundamental question centers on how incentive programs will work, because converting these buildings is not a simple task,” explained Farrell, whose firm worked with PMC Property Group to convert the former GlaxoSmithKline headquarters tower in Philadelphia into 360 apartment units in 2019. “It’s much simpler to develop a new building from the ground up than it is to rip out the guts of a building and do a conversion.”

The Franklin Tower Residence project. Developer PMC Property Group changed out the full mechanical, electrical and plumbing systems, which freed up room to create a rooftop lounge and outdoor deck. Image courtesy of Robert Deitchler/Gensler

Helping hand

Some cities and states are already crafting incentive policies. In June, San Francisco began seeking developer input on how the city could help speed up or enhance conversions through regulatory changes, financial incentives and other means. That followed approval of legislation that provides zoning and fee exemptions, among other benefits, to help streamline the reuse process.

“The number one thing that is needed for conversion projects is city support,” said Thomas Cox, founder & managing principal of TCA Architects. “We’re seeing a lot of the tech industry meltdown, especially in the Bay Area, and San Francisco needs to get people back downtown.”

To the south, Los Angeles continues to expand and modify a 1999 adaptive reuse policy that has fueled the conversion of some 12,000 new housing units by expediting approvals and relaxing code and zoning requirements, according to the city’s planning department. That program was in place when Forest City Enterprises converted three office buildings that added 745 downtown units to the market early this century, said Cox, who worked on the projects. The properties were largely acquired at discounts, which helped financial feasibility. Cox sees a similar dynamic at play today.

Currently one of his developer clients pursuing conversions is negotiating with a bank that took three heavily vacant downtown Los Angeles office buildings back to either acquire the properties or partner with the lender in a deal. The goal is to turn one of them into housing after moving tenants into another building. If it succeeds, the developer will repeat the process, Cox said.

“What we’re seeing now is a very large change in ownership of these office buildings—lenders are taking them back and are discounting the pricing,” he said. “That’s opening the door for developers to step in and consider a residential conversion.”

The Franklin Tower Residence project spread out amenities such as a media room, basketball court and spin studio throughout the building. Developer PMC Property Group changed out the full mechanical, electrical and plumbing systems, which freed up room to create a rooftop lounge and outdoor deck. Image courtesy of Robert Deitchler/Gensler

In limbo

The office-to-residential conversion theme is hardly new and tends to emerge in the commercial real estate cycle’s recession phase. Following the savings and loan crisis, New York City launched the 421g Tax Abatement program in 1996 to facilitate office-to-residential conversions in downtown Manhattan. The initiative helped convert roughly 13 million square feet, or about 13 percent of the downtown office market, into 12,865 units in 11 years, according to New York’s Citizen Budget Commission.

Such incentives don’t exist today, however. Despite support from the governor and New York City Mayor Eric Adams, a proposal geared toward facilitating residential conversions south of 60th Street in Manhattan failed to clear New York’s General Assembly this year. That could change if more office owners can’t refinance their debt and a mass of assets wind up with lenders, Jantz noted. But for now, he suspects lenders are addressing troubled loans on a one-off basis.

“My gut tells me that lenders don’t see a reason to change that approach. I think everybody believes that people are going to eventually return to the office in a more robust and regular manner,” he reported. “Going to the office five days a week may not come back, but if you have people working the same three to four days during the week, you’re going to need office space.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.