Typically a Turtle, Industrial Could Be Real Estate’s New Hare

Often deemed a relatively unexciting sector marked by incremental growth, the asset category is arguably the hottest in real estate, thanks to changing consumer and lifestyle trends.

By Paul Fiorilla

Traditionally seen as unexciting and featuring incremental growth, industrial has become arguably the hottest sector in real estate because of changing consumer and lifestyle trends.

Although the sector’s growth has myriad reasons, the chief force behind the burgeoning demand for industrial space is e-commerce. Demand is measured not only in square feet, but also new facilities with modern technology and in locations closer to population centers. That has led to robust development and atypical growth in rents and property values.

The impact of e-commerce on industrial is in its early stages, says James Bohnaker, a senior economist for CBRE. “The structural tailwinds are all very strong and pointing in the right direction,” he said.

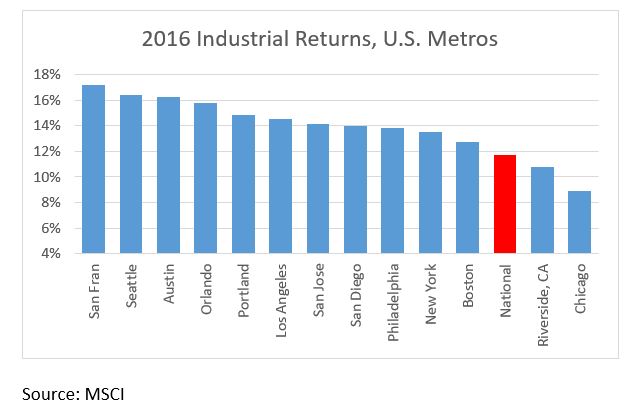

Industrial property values are rising fast. According to research and analytics firm MSCI, U.S. industrial properties returned 11.7 percent, the highest of any property segment in 2016, and well above the 7.7 percent all-property average. MSCI found that double-digit returns were widespread in metros across the country. As might be expected, industrial property returns were highest in rapidly growing western and southern metros that are attracting jobs and population growth, including: San Francisco (17.2 percent), Seattle (16.4 percent), Austin (16.2 percent), Orlando (15.8 percent), Portland (14.8 percent), San Jose (14.1 percent) and San Diego (14.0 percent). However, returns also were solid in markets where overall property value growth was less robust, including: New York (13.5 percent), Philadelphia (13.8 percent), Boston (12.7 percent) and Chicago (8.9 percent).

Whether investor and tenant demand can continue at above-trend levels is an open question, and there are concerns about whether the sector’s bull run will be curtailed by issues such as overdevelopment, a cooling economy or protectionist trade policy.

Slow, Steady Growth Sector

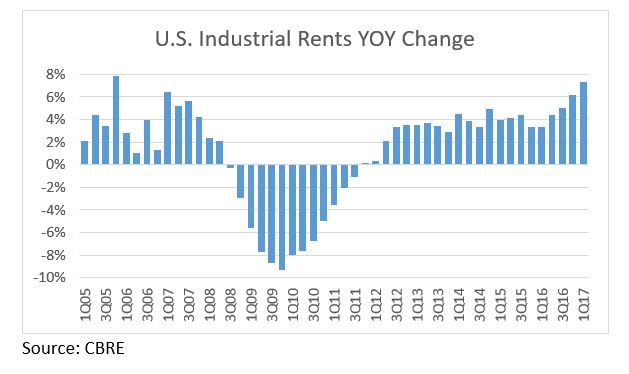

Industrial has long been a relatively unexciting segment of commercial real estate. Warehouses and processing centers are functional and anonymous, mostly situated away from trendy locations, and rent growth historically has been slow-moving. It’s hard to make a quick profit or flip industrial properties, which rules out some types of capital sources, and owners need some operational expertise, which rules out others.

Dynamics of the industrial sector are changing for many reasons, particularly the growth in e-commerce, foreign trade and technology. The old model for warehouses was to cluster them near ports or out-of-the-way spots, where products would be stored and shipped to retail locations. But that has changed as today’s consumers want to buy products online and have them delivered almost immediately. U.S. consumers purchased nearly $400 billion of goods online in 2016, and E-commerce sales have been growing by about 15 percent per year.

The new retail model requires distribution centers that are compatible with online purchases—equipped with state-of-the-art technology and high ceilings and located near population centers. Growing demand for those types of facilities has supported development of new space to support retailers such as Amazon and Walmart. That has put industrial in the unusual position of competing for land with property types in higher-cost locations.

“The focus in the past was where to find the cheapest labor,” said Jay Pelosky, principal at consulting firm Pelosky Global Strategies, speaking at last week’s MSCI Real Estate Investment Conference in New York. “Now we’re talking about how to get close to the customer.”

E-commerce isn’t the only driver of warehouse demand, though. The rise of sustainable energy production, legalization of marijuana in some states and growing global trade has also played a role in the increased use of distribution and warehouse space. The demand is broad-based, some near ports in metros such as Inland Empire, Seattle and Central New Jersey or in states such as Colorado where marijuana is sold legally.

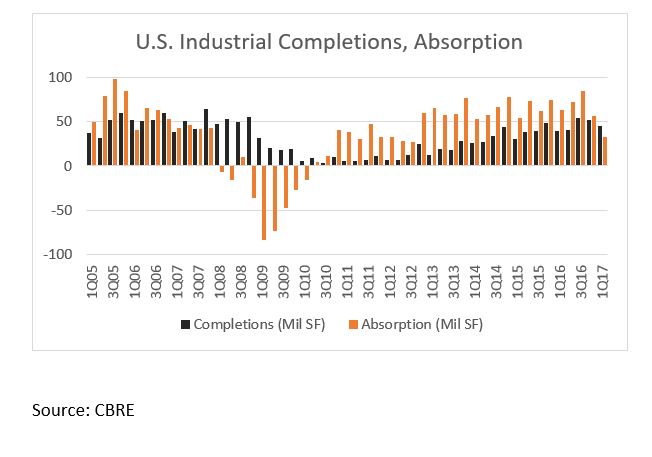

With so much absorption, occupancies of industrial space have crept higher as the economy recovered from the last recession. Since the beginning of 2013, 1.1 billion of space has been absorbed. After peaking at 14.2 percent in 2Q10, industrial vacancy rates steadily declined to 7.9 percent in 4Q16 before rising by 10 bps in the first quarter of 2017 (CBRE).

Like all commercial asset classes, development was stalled in the wake of the Great Recession, but now construction is on the rise. Since 1Q13, about 600 million square feet of space has been developed, compared to about 200 million square feet between 2009 and 2012 (CBRE). Some 187 million square feet was added to inventory in 2016, up 19.3 percent year-over-year and the most since 2008 (CBRE).

With occupancy rates at or near all-time highs in most markets, supply might not be an issue. The question is whether new development will continue and eventually overshoot, dragging down occupancy rates and slowing or even flattening rent growth.

Capital Trends

Industrial property sales in the U.S. totaled $59 billion in 2016, down from the sector’s peak volume of $78 billion in 2015, according to Real Capital Analytics. The decline reflects the fact that several large portfolio trades and mergers and acquisitions closed in 2015, and a lack of motivated sellers, not any shortage of capital.

In fact, many institutions would like to grow their industrial holdings but find it difficult to break into the sector. For one thing, individual property values are relatively low, and there are no trophy assets, so institutional investors with large pots of money to invest can only get into the market by buying large portfolios. That produces a “portfolio effect,” where institutional buyers must pay up for large portfolios with lower acquisition yields.

“It’s a hard sector to get into,” said Jacques Gordon, global head of research and strategy at LaSalle Investment Management, speaking at the MSCI conference. “It’s hard to buy and there’s not a lot of it.”

Questions About Global Trade

Since global trade is one of the big drivers of industrial use, the direction of U.S. trade policy could have a major impact on future demand, not only the amount of space needed, but the location. During his campaign, President Donald Trump said he wanted to impose steep tariffs on goods imported from countries such as China and Mexico, and rewrite trade agreements that he said had negative effects on manufacturing communities in the U.S. Republicans in Congress have also proposed reforming the tax code to include a “border adjustment tax,” which would have the effect of increasing taxes on businesses that import goods and lowering them on exporters.

To date, no proposals for tariffs or taxes have been introduced. While it is unclear what will be proposed and what can make it through Congress, it’s safe to say that the administration has a view of trade that differs from all recent predecessors, regardless of party. U.S. policy has been about open borders and increasing trade, while Trump’s view is nationalist.

Trade agreements such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) have been about coordinating among countries in a region the mismatch between labor, resources, capital and consumers. For example, in NAFTA (simply put), Mexico has low-cost manufacturing, Canada has resources and the U.S. has consumers and capital, Pelosky said. While there are inevitable downsides, trade agreements give businesses access to markets and resources that boosts growth in all countries.

Pelosky noted that although Trump’s policies are not yet formed, and he has yet to nominate candidates to positions in the federal bureaucracy who would form and implement trade policy, that the new president is likely to soften his campaign stances once he realizes the benefits of cooperation between countries. Trump’s nationalistic rhetoric “comes from a good place, he realizes the need to work,” Pelosky said. “How to address it is the question.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.