Western US Drought: How It Impacts CRE

Developers are responding with new measures to address the crisis.

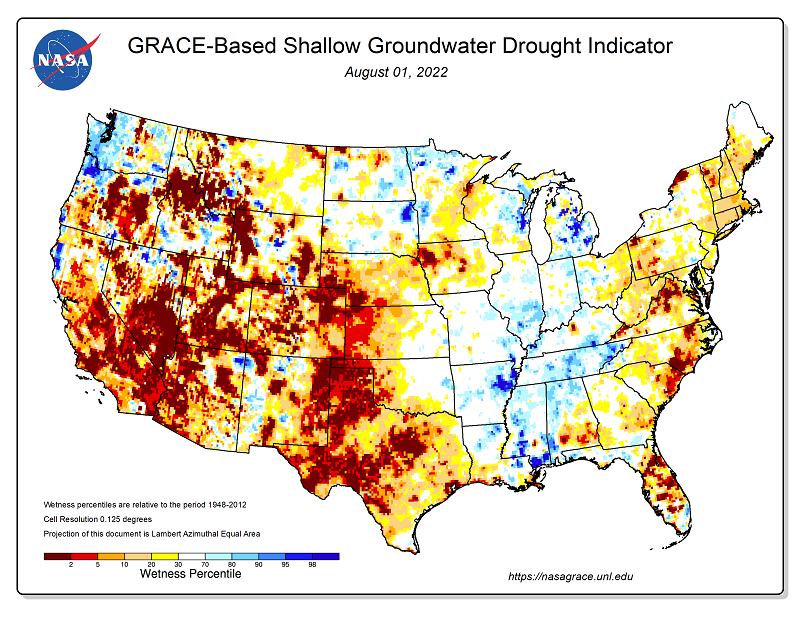

The arid regions of the Western U.S. are presently experiencing the driest two decades in at least 1,200 years, according to the Water Wise report issued by the Urban Land Institute. This is not a singular case, because about half the world’s population is facing severe water scarcity for at least a few months each year, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s 2022 assessment report. Drought is just one catastrophic phase, followed by others: wildfires, floods, erosion and ultimately, famine.

In June, California and six other Western states were given two months to come up with an emergency plan to stop using between 2 and 4 million acre-feet of water in the next year. Otherwise, the Bureau of Reclamation will make the cuts itself. It’s a shocking volume because it represents somewhere between 15 percent to 30 percent of all Colorado River water use.

An August update on the policy requires that, in 2023, Arizona will have to reduce its water usage by 21 percent and Nevada by 8 percent, with California suffering no reduction (so far).

Water rights (and wrongs)

Marianne Eppig, director of Urban Resilience at ULI and author of the Water Wise report, explains that in the West, overallocation of water rights is how things work. Western water law is governed by “prior appropriation.” In other words, the first person to divert water from a river or stream and put it to beneficial use is entitled to continue that use without interference from other users who make subsequent claims.

Hence, this law uses the “first in time, first in right” model and is based on use rather than landownership. This means that the first state in line must continue to use water just to keep the right because if the water allocation is not used, they lose their guaranteed access to it. “This system incentivizes water rights holders to use 100 percent of their historical water rights, whether they need them or not,” noted Eppig.

The result? This system limits access to water in a region facing long-term aridification, meaning that there is not enough to go around—as is the case with the Colorado River basin.

There is another water law, the Eastern riparian water law, which originated from England’s system of water law and is based on the ownership of riparian land—the land bordering a river, stream or lake. In addition to being based on landownership, riparian water rights require upstream water users to be reasonable and respect the rights of downstream water users and the public’s interest in safe, clean, plentiful water.

Drying out

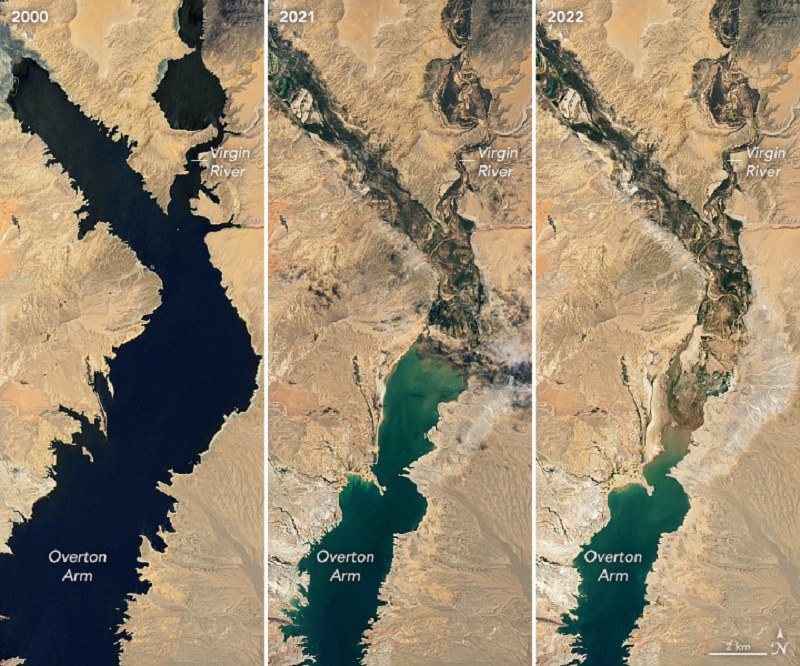

The water supply and demand of the Colorado River basin have been out of balance for more than two decades, clarified Jennifer Pitt, Colorado River program director at the National Audubon Society. “We know that because no water has flowed out of the downstream end into the Colorado River Delta.” She went on to say that since 2000, the major Colorado River reservoirs have declined by an average of 2 million acre-feet annually. Some rules have been established along the way to set shortage volumes for lower basin states, but those rules underestimated how quickly climate change would diminish river flows.

Basically, the challenges in the Colorado River basin exist because its 20th-century infrastructure is based on legal framework created in the 19th century and is far from matching the water needs of the 21st century, said Pitt. There is some good news as, according to Eppig, the existing management guidelines are scheduled to be renegotiated by 2026, when the current ones expire. In the meantime, how exactly are these states going to reduce water usage by such a major volume, remains to be seen.

“The Law of the River has some provisions for allocating shortages, but they have not been tested at this scale,” said Pitt. The Colorado River basin states—Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah and Wyoming—can devise a shortage-sharing scheme that avoids crises.

Typically, cities have junior water rights and, according to law, would have to apply water use restrictions before agricultural irrigators. However, in order to reach agreements, the states must lead, noted Pitt. Currently, some 80 percent of all Colorado River water is used to irrigate agriculture and the remaining 20 percent supplies cities and industrial uses.

“In the absence of a seven-state collaborative agreement, we are told to expect federal action and anticipate that litigation would follow. In that event, the reliability of everyone’s water supplies is in question. All of us who rely on water should be asking our water leaders and elected leaders to reach a collaborative agreement to share Colorado River water shortages,” added Pitt. She believes that investing in watershed resilience, naturally distributed shortage and water conservation in cities and on farms would help temporarily.

Rules and policies for the built sector

Climate change has led to greater heat and aridity, which have increased droughts’ frequency, intensity and duration to such an extent that they are now being acknowledged by government officials as a threat to communities. Hence, policies to address water issues are enacted but with a twist, as noted in ULI’s report: If, until not long ago, these policies focused on water supply management, these are now centered on the demand side of water management—conservation, efficiency and reuse.

READ ALSO: A Deep Dive Into Water Management Strategies

Expectedly, the built environment is the main target for these policies. Some of the fastest-growing states in the last decade are Texas and the ones in the Western U.S. The pandemic pushed many residents into suburban regions, which materialized into a good amount of new development in these areas. Suburban developments, according to ULI’s report, often include large, landscaped lots that require more water to maintain. In addition, the farther away from municipal water sources a project is built, the more resources it needs to either connect or find its sources of water. The latter can be quite expensive to construct and maintain.

Presently, across California, some rules have been set to more wisely use those 20 percent that supply cities and serve industrial purposes, most of them focusing restrictions on outdoor watering, which accounts for roughly half of all urban water use.

Continuing the work of former Governor Jerry Brown, who mandated a 25 percent reduction in water use in the face of a severe drought in 2015, last year, California Governor Gavin Newsom asked residents to reduce water consumption voluntarily by 15 percent. The result was impressive—water use in the state was 16 percent lower in 2021 than it was in 2013. Still, single-family homes typically use the most water of any customer sector of North American water utilities, according to ULI’s report.

READ ALSO: Go With the Flow: Clean Water Expert on Sustainability, Value Creation

To reduce water usage, residents can limit outdoor irrigation by planting native and drought-tolerant plants. Eppig reminds that there are many water providers and municipalities that offer cash-for-grass programs, paying residents to replace their grass with water-smart landscaping. In addition, there are the EPA WaterSense-labelled fixtures and appliances that fall under rebate programs at many water providers and municipalities. She strongly recommends upgrading the technology solutions to include not just water-efficient fixtures, appliances and irrigation, but also consider water reuse, smart metering and submetering, as well as better data collection on water availability and leaks.

While it’s common knowledge that real estate development follows demand, and demand is strong in Western U.S., when looking at the map illustrating groundwater conditions, the first question that comes to mind is—how come there aren’t regulations to which any given region can withstand in terms of population expansion and water capacity?

In Western U.S., water sources are drained and “most rivers have been dammed to capture high spring runoff and to recapture water downstream for subsequent use,” the United States Army Corps of Engineers reported. Municipalities have a hard time deciding whether to allow new developments, as this means more pressure on the already withering water supplies. Without the ability to build more, housing prices will continue to increase, deepening the affordability challenge.

One good thing the pandemic left behind is that people are less restricted to a location in relation to their dream jobs—given that the respective jobs can be performed remotely. This allows for expansion in metros less drained of their natural resources, areas that allow for horizontal expansion not just vertical. Of course, this would be a lengthy process, but it looks increasingly less of an option and more of a necessity.

Drought impacts insurance, energy prices

The impact of drought on real estate also includes property insurance. Investors and developers will become increasingly cautious to build in parts of the world that are at risk. In some areas, insurers are simply unwilling to provide insurance if there’s high risk of wildfire, which is a direct consequence of drought.

The National Centers for Environmental Information reports that annual losses caused by drought are close to $9 billion. But in addition to these direct losses, another economic impact is related to energy prices: While nationally, hydropower provides about 7 percent of energy, in Western U.S., this number is three times higher. As water levels in the reservoirs decrease, hydroelectric plants are at risk to stop producing energy.

Images were captured on July 6, 2000, July 8, 2021, and July 3, 2022, by Landsat 7 and Landsat 8. Courtesy of NASA

Water levels in lakes Powell and Mead have already dropped to around 25 percent of capacity, so the federal government mandated an extra release of water from the Upper Colorado River basin and delayed a release from Lake Powell. In fact, by 2024, projections show that water levels in Lake Powell could drop too low for hydropower turbines to operate and generate electricity.

Another example is Hoover Dam—its hydraulic turbines have already been replaced with models that can work in shallower water. While this solution kept the energy running, there’s only so much technology can do. The federal Bureau of Reclamation has reported that the lower water levels have already reduced the dam’s electric output by one-quarter. Furthermore, with less water available, the energy produced by coal, natural gas and nuclear power plants is also at risk, because all of these require water to cool down their systems.

Droplets of hope

Yet, water-smart development has a documented market advantage. As Aaron Tartakovsky, CEO of Epic Cleantec puts it, “in the 21st century, we should not have to rely on whether or not it rains to determine if we’ll have enough water supply for our communities. We have the technological solutions today, we just need to deploy them faster.”

He is referring to onsite water reuse, a technology he developed with his father, Igor Tartakovsky, as part of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation’s “Reinvent the Toilet Challenge.” The tech captures and processes a building’s wastewater—either black or gray—and produces three outputs: recycled water for nonpotable applications—such as toilet flushing, cooling tower makeup, irrigation and laundry—recovered waste heat energy and repurposed organic solids for use as a natural, carbon-rich soil amendment.

Epic’s first installation was in the 754-unit NEMA building in downtown San Francisco with multifamily developer Crescent Heights. As of 2021, Epic is operating San Francisco’s very first approved and operational greywater reuse system in Related’s newly opened 39-story Fifteen Fifty building.

The company has since partnered with other major developers across the U.S. with planned developments in multiple states, including the 1.3 million-square-foot Park Habitat commercial project in San Jose, Calif., with developer Westbank. “In this project, designed to seamlessly integrate nature into the built environment, Epic will be producing 30,000 gallons of highly purified recycled water each day to irrigate 20 stories of plant life and diverting tens of thousands of pounds of wastewater organics from landfill to produce high quality, carbon-rich soil products for local reuse,” said Aaron.

Younger generations, especially, prefer developments equipped with water-efficient fixtures and appliances and water monitoring systems, so this type of technology is an appropriate answer to their needs. More so, Epic Cleantec’s system works across different property types—commercial and residential, corporate offices and campuses, community-scale developments, stadiums, golf courses and even wineries, breweries and distilleries.

“On average, we are able to reduce a commercial property’s water demand and utility costs by up to 95 percent given the higher usage of non-potable recycled water—for toilet and urinal flushing, cooling tower makeup water, irrigation and laundry. In many of the projects that we partner with, this translates into millions of gallons of water recycled each year, an especially important statement for any project in our drought-prone Western states.”

Literally greener

FirstService Energy President Kelly Dougherty added that, in addition to smart irrigation and water monitoring systems implemented at the properties they work with, they counsel the communities to review landscaping: Communities in Arizona could decorate their green spaces with agave or cacti, rather than a traditional bush more commonly found in the northern regions of the country. “This small change could help a community save hundreds of gallons of water on a yearly basis,” she said.

Another method to reduce water waste is limiting the amount of paved surface area within a community. Certain surface areas such as driveways and parking areas are necessary, but “creating a more thoughtful design that replaces unnecessary paving with green spaces is beneficial for communities because it allows water to permeate the soil. By having a balanced combination of surface areas and green open spaces, communities are better able to control their water usage,” explained Dougherty.

Green buildings are steadily becoming the norm among renters, displaying higher occupancy and retention, and lower vacancy. These buildings use anywhere between 20 and 40 percent less energy and water, and owners reported saving about 15 to 20 percent on bills. Dougherty confirmed that, as of late, a greater number of people are asking more questions about the sustainability and resilience of communities. Questions like “Is this a LEED-certified building?”, “Is there a green director or a green committee?”, “Does the building have a plan on how they will achieve zero-net?”, “Is there a robust recycling program in place and are there compost areas?” are becoming quite common.

Similarly, property managers are touting a property’s green features to attract prospective renters and buyers. Many of the buildings FirstService Energy works with, in New York and Illinois, have a labeling system that informs future and current residents of the green features in place.

“While green features aren’t the only deciding factor in purchasing a property, they are becoming increasingly important. Buyers are becoming more inquisitive about sustainability, and realtors are following suit with enhanced fluency about the benefits of green features. This increased knowledge, combined with regulations coming from both state and federal levels, is a good indication that people will seek out sustainable communities in the future.”

Furthermore, green buildings not only offer a better ROI, but they’re also a solid venture as, according to the U.S. Green Building Council, upfront investment in water and energy efficiency measures increase property values by 10 percent or more in some cases.

There is not a universal recipe that can be applied to all property types and certainly not across the country. Properties in the Western U.S. will spend more than those in the Southeast mainly because the western region is considerably drier. “It’s safe to say that for established communities to implement water-saving technologies and measures funding is required. Moreover, these aren’t one-time investments, and communities should budget for the ongoing expenses to ensure green features are properly maintained in order to guarantee a return on their investments in the long run,” added Dougherty.

It’s all about education

Communities are most resilient when residents are aware of the scope of current and potential water shortages and engaged in improving the situation individually, according to Dougherty. She says it’s equally important to encourage this engagement organically, and what seems to make the most impact is a grassroots effort within a community.

“Residents can create water conservation committees to educate fellow residents on ways they can help save water. While property managers and association boards can help mitigate disasters, each resident must cooperate and do their part. Moreover, when the request for water-saving lifestyle changes comes from resident-driven education initiatives, they are typically more impactful,” she said.

It is incumbent upon everyone to do their individual part to conserve water during these prolonged periods of water scarcity, concluded Tartakovsky. These include simpler actions like being mindful of turning off the tap when brushing teeth or doing the dishes.

You must be logged in to post a comment.