What’s Pushing the Pace of C-PACE

Experts at the ULI fall conference shared the latest trends in this alternative tool for financing upgrades.

“We are getting pulled into this need for energy efficiency and we’re getting pushed into it at the same time.”

That is how a current challenge for building operators was summed up by Cliff Kellogg, executive director of the C-PACE Alliance, during a panel on C-PACE financing at ULI’s Fall Meeting. Energy efficient properties not only attract tenants, they also address a growing number of regulatory mandates.

Designed as a lower-cost alternative to mezzanine debt and equity, Commercial Property Assessed Clean Energy (C-PACE) has been around for a decade to finance upgrades that reduce energy consumption and generate renewable energy. It requires an independent analysis of utility savings and cost effectiveness and comes with fixed-rate financing for the useful life of improvements (up to 30 years).

READ ALSO: Commercial PACE Finance Faces a Turning Point

The key mechanism for the strategy is an assessment on the owner’s property tax bill. The terms are negotiated between the property owner and the private capital provider. The strategy enables a developer to convert a capital expense it into an operating expense on the assumption that the savings in operations costs will exceed the cost of the loan.

Because the change to the property tax assessment requires authorization by the state legislature, and each local government must opt in, adoption has been gradual. But after a relatively sluggish first seven years, the past three years encompass about 85 percent of all financings to date.

Push and pull

Behind the remarkable growth C-PACE has experienced in recent years are the green initiatives that have been implemented in places like New York City, California, Washington state and Washington, D.C. These are prompting owners and developers to find capital sources for retrofits or energy efficiency measures in new developments. Another powerful incentive is the ESG push coming from institutional investors, as owners and occupants must report the actions they’re taking to reduce their carbon footprint.

COVID-19, too, has accelerated the progression. When capital for projects suddenly dried up, their owners had to find alternatives, and C-PACE checked many of the boxes, noted Mansoor Ghori, the CEO & co-founder of Austin-based Petros PACE Finance. From one of the last options in the capital stack, C-PACE rose to the top.

For their part, mortgage lenders recognized that the financing strategy increases a property’s value. Energy savings offset C-PACE loan costs; the program improves cash flow and the owner’s ability to pay down its debt.

C-PACE is “rescue capital,” said Kunal Mody, CEO of Blueprint Hospitality, a developer which has been using the method for 10 years. “It’s a new way to maximize your capital back and make sure you have enough cash on hand so that you’re not hitting your loan covenants,” he said.

PACE in practice

The value of C-PACE loans has also increased dramatically, from the $1 million to $50 million range. Wafra Capital Partners and the Nightingale Group secured $89 million in C-PACE financing for the rehabilitation of 111 Wall St. in Manhattan, a 1 million-square-foot office property built in the 1960s.

Included were upgrades to the HVAC and MEP systems, as well as fully redundant power systems. These dovetailed with New York City’s Local Law 97, which requires buildings larger than 25,000 square feet to meet energy efficiency and greenhouse gas emissions limits by 2024.

A key step is the energy audit, which determines how much PACE financing the project is eligible for, said Ryan Hoff, project manager at Bernhard TME, which performed the audit for 111 Wall. Because changes are much easier to make during design than after installation, the energy audit should be conducted as early in the process as possible, Hoff noted.

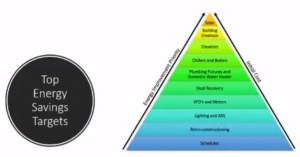

At 111 Wall, measures eligible for PACE financing ranged from LED lights and asbestos removal to efficient HVAC systems, elevators and plumbing fixtures. The improvements lowered operating costs and cut carbon emissions 42 percent. All told, the project has saved about $3.3 million annually in energy operation and carbon offset costs.

In case a property with an active C-PACE loan comes under new ownership, the loan automatically transfers to the new buyer or can be dealt with as part of the proceeds. However, it is only 1 or 2 percent of the property value that’s in front of the bank at any one time, explained Ghori.

You must be logged in to post a comment.