Whither Goest Interest Rates?

By Robert Bach, National Director of Market Analytics, Newmark Grubb Knight Frank: Common wisdom among economists is that if you forecast a specific number, don’t forecast the date when that number will occur, and vice versa. This applies to interest rates.

By Robert Bach, National Director of Market Analytics, Newmark Grubb Knight Frank

Common wisdom among economists is that if you forecast a specific number, don’t forecast the date when that number will occur, and vice versa. This applies to interest rates. I am 99.9 percent certain the yield on the 10-year Treasury note will hit 5 percent, but don’t try to pin me down on the date. I’m willing to go on record that it won’t be this year, and I’m also going on record that the 10-year yield will end 2014 higher than 2.73 percent, where it was perched on March 31. I might get more specific at the end of this article if you twist my arm.

Common wisdom among economists is that if you forecast a specific number, don’t forecast the date when that number will occur, and vice versa. This applies to interest rates. I am 99.9 percent certain the yield on the 10-year Treasury note will hit 5 percent, but don’t try to pin me down on the date. I’m willing to go on record that it won’t be this year, and I’m also going on record that the 10-year yield will end 2014 higher than 2.73 percent, where it was perched on March 31. I might get more specific at the end of this article if you twist my arm.

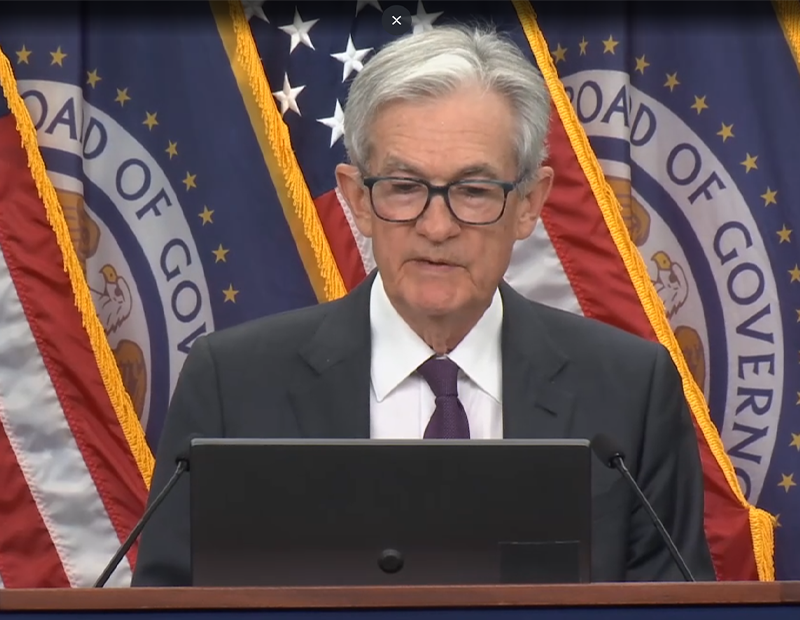

The reason I don’t like to be pinned down is that the 10-year yield and its sidekick, inflation, have confounded analysts throughout the recession and recovery, now approaching the end of its fifth year. Early in this cycle, the favored scenario among many was that the Treasury Department and Federal Reserve would have to pursue a policy of low interest rates/high inflation so households, businesses and governments could repay their massive debts from the financial crisis with inflated (less valuable) dollars – the ultimate bailout. But it didn’t turn out that way. Despite stimulus packages and rounds of quantitative easing to keep interest rates low, inflation remained tame and in fact has fallen below the Fed’s target rate of 2 percent for the past two years. Meanwhile households and businesses have shed their excess debt while the federal government’s deficit has returned to historical norms thanks to sequester-mandated spending cuts and improving tax collections – all without any whiff of inflation.

Some financial analysts developed a following by hammering the Treasury Department and Fed for their unconventional policies, which, they argued, would trigger higher (if not hyper-) inflation or, even worse, another round of financial contagion spreading through global markets. These analysts sought to attract defensive-minded clients who had been hurt by the financial crisis and were willing to believe that the U.S. and/or European governments were setting the stage for another one. These analysts convinced their clients to hedge against this risk just as the Fed was setting the table for a raging bull market in home-grown, garden variety stocks.

What, you might ask, does this have to do with commercial real estate? Our industry owes a tip-of-the-hat to ex-Fed Chairman Bernanke who, though he was slow to recognize the gathering storm clouds, was quick to embrace strategies that delivered the dramatic recovery of property prices and the more measured recovery of leasing markets, which promise to gain momentum this year. I’ve read articles recently suggesting this period of low inflation and interest rates could go on for years. Just remember, however, that nothing lasts forever: not the financial monster that nearly swallowed the world, nor the economic stability that has endured for the past five years, earning strong returns for investors in stocks and real estate.

Fortunately for analysts who go out on a limb, people tend to have short memories. So, despite my description of the pitfalls, let me risk answering the question posed in the title of this piece. The 10-year Treasury yield will end the year around 3.5 percent, about 50 basis points higher than where it began the year. This will signal both an improving economy and a return of inflation back to the Fed’s target level of 2 percent. But if I’m wrong, I don’t want to hear about it. Deal?

You must be logged in to post a comment.