Who Will Bankroll the Greening of CRE?

Climate tech innovators are ready to solve real estate's challenges. But it’s going to take some capital.

The evolving climate tech landscape is a mosaic of innovations, some incredibly consequential and some destined to fail. As expected, the jury’s still out on many of them. One thing is certain, however. Commercial real estate’s reckoning with its role in climate change and climate solutions is here.

Approximately 40 percent of global emissions are related to real estate. That, “combined with new regulations, both in the U.S. and globally, changing tenant preferences (and) a preference for allocation of capital toward greener strategies” explain why climate tech is shaping up as a critical topic,” observed Abby Levine, leader of Deloitte’s real estate strategy and sustainability practice.

READ ALSO: How Can CRE Manage Climate Risk?

There is always a lot of excitement around something as promising as climate tech, but understanding the various subsectors and the granular nature of this new asset class requires digging down and unearthing specifics, said Mark Grinis, EY‘s Americas real estate, hospitality and construction leader.

“You start with an incredible hype, but then you move to a bit more of an understanding and where the things that are that give immediate return on investment that are functional, that are practical and applicable,” he explained. “I think we’re kind of moving into that.”

Climate tech innovations span the lifecycle of a property from building materials, windows, lighting tech, heating and cooling tech to solutions used to manage the building, carbon accounting reporting, and distributed energy solutions.

Building new commercial real estate properties with climate tech in mind, even as a key focus, is not enough, said Levine, who is also a member of Deloitte’s sustainability, climate and equity leadership team. Upgrading existing buildings with these technologies is essential, but both greenfield and brownfield projects will require capital.

One of the year’s hottest topics, artificial intelligence, will have a role to play in climate tech that is likely not yet fully understood. “It’s a super exciting time,” Levine remarked. Similarly, “the parallels of proptech and climate tech are following similar trends,” said Grinis.

“Technologies that benefit commercial real estate—and that we have helped to install in buildings across the U.S.—can range from heat pumps and electric vehicle charging to air sealing and energy efficiency windows and beyond,” added Jon Moeller, COO at Brooklyn-based climate tech startup BlocPower.

Demand, supply and insurance

Demand for properties with advanced climate technology will undoubtedly shape the pace of implementation. One question to ask is “What’s the cap rate for people that are buying these buildings?” said Grinis. “What percentage of institutional capital has said ‘We’re only going to do this quality, but we’ll pay up for it’?”

For some developers, insurance companies may force their hand. Grinis noted that some developers in recent years have been informed that their insurance rates for completed projects need to be re-underwritten because the insurance cost for the property has doubled due to increased climate-related risks.

READ ALSO: Why CRE Insurance Challenges Are Intensifying

“In California and other places, you have major insurers that are pulling out of the market and obviously that is going to change the ultimate cost,” said Grinis. “If you’re located on or close to the water, how are you addressing that? I know a lot of developers (whose properties’) first two floors are being designed in a certain manner that is anticipatory of flooding and will be resilient to that to the extent it happens.”

Backing small firms

In the global climate tech game, the U.S. is keeping pace with other leading countries. “I would have said a few years ago that the U.S. is lagging in an investment context, compared to other countries, particularly to (countries in) Europe and Asia, but the U.S. has certainly caught up,” Levine said.

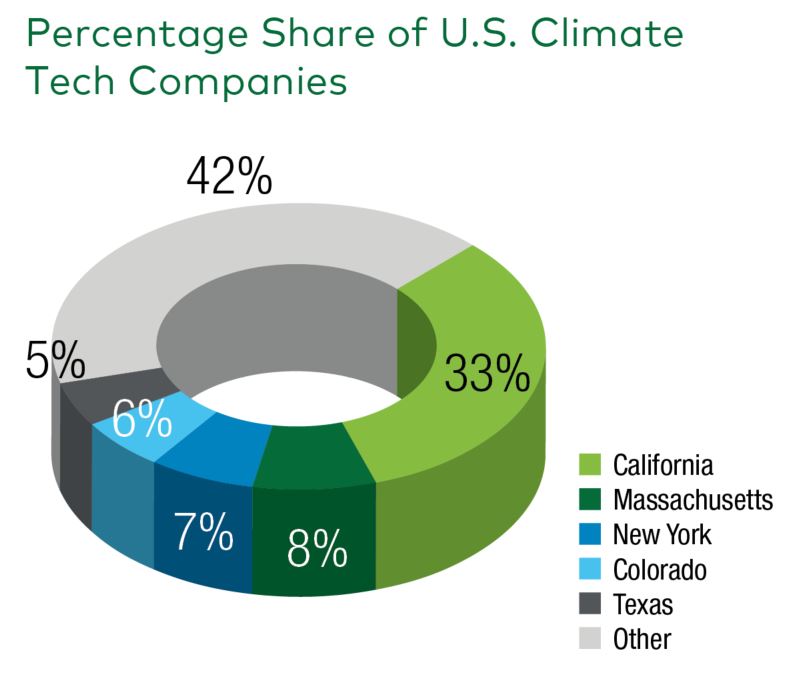

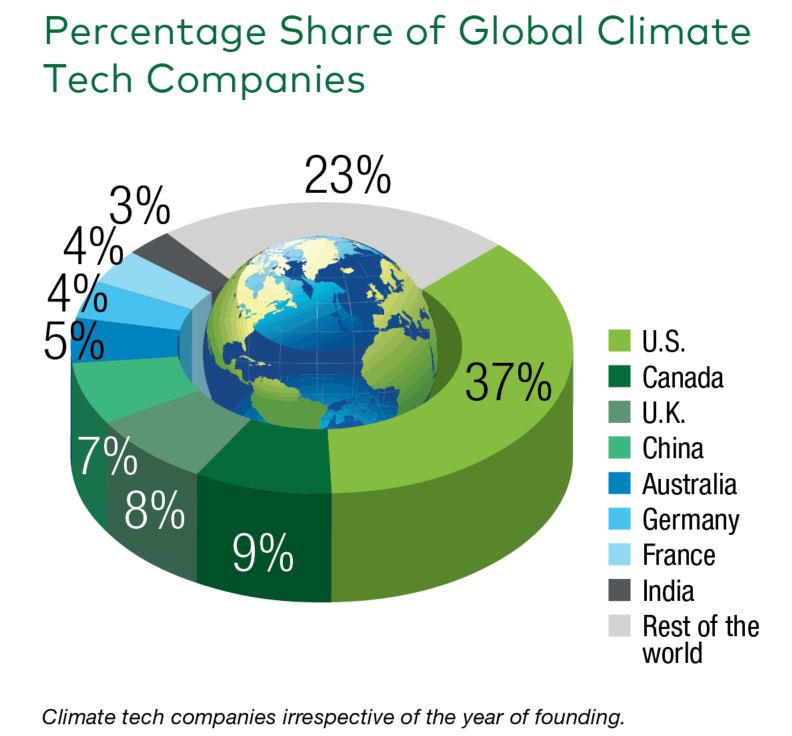

Eight countries account for a majority of global climate tech investment and entrepreneurship, Levine noted: Australia, Canada, China, France, Germany, India, the U.K. and the U.S. From 2000 to 2022, approximately 2,400 climate tech companies were founded, 9,000 funding deals executed and $148 billion invested globally, a recent report from Deloitte shows. The report stated that activity picked up significantly after 2013. The U.S. leads the pack in terms of global climate tech companies by country at 37 percent. Canada places a distant second with 9 percent, while the rest of the world’s countries beyond the top eight account for 23 percent.

READ ALSO: C-PACE’s Moment Arrives

“The U.S. has always been an engine of ingenuity,” said Moeller, who credits a recent blend of domestic policy and geopolitical urgency as accelerating the pace of climate tech adoption. “Innovation and investment is the key to this and with significant federal and local legislation, like the Inflation Reduction Act or Local Law 97 in New York City, the U.S. has spurred historic investment in climate technology across sectors. Europe is also increasingly reviewing electrification options, particularly as high fossil fuel prices and availability issues related to Ukraine.”

For every niche in climate tech, there are startups that are vying for funding. “There are a range of solutions and technologies that can make a big difference to the commercial real estate sector,” said Moeller. “Weatherization is often a cost-effective and good first step with quick payback—and if an owner is considering electrification projects later, it makes sense to ensure an effective building envelope. “Depending on the application, focusing on centralized applications like hot water or central heat with electric alternatives makes sense,” said Moeller.

One area Grinis noted as particularly interesting is 3-D modeling, which he says may be able to drive more efficient design and prevent the over-engineering of buildings. “In 100 years, we barely moved the needle from an efficiency perspective in the construction space,” he remarked. “To the extent now, where you have the digital tools to build and analyze and do everything in a 3-D capacity… you can really learn a lot without putting one shovel in the ground. I think the construction space looks to benefit a lot, and I’m seeing a lot of R&D going into that.”

READ ALSO: New Pathways to Green Building With Mahesh Ramanujam

Many of these companies are less than half-a-decade old and rely on venture capital. “When you see something really get traction, then you see the second-stage venture really come in a big way and you’ll see $50 million to $100 million, because there’s a line of sight toward (an economically viable product),” said Grinis. “If you build a better mousetrap around glass or concrete or you name it, the addressable market is gigantic and so the returns can be tremendous.” However, first rounds of funding tend to be in the single-digit millions.

“The need for climate tech innovation, especially in high-emissions sectors, makes venture-stage funding crucial to the fight against climate change,” PwC said in a recent report. “But if climate tech is to deliver significant impact, it will take much more financing than is currently flowing into the category: not just venture capital, but also growth capital to help start-ups expand quickly and financing to help companies and governments deploy climate tech solutions en masse.”

Moeller pointed to his own firm’s fundraising round of $150 million earlier this year as a sign that traditional financing sources are taking notice of climate tech’s opportunity. The financing included more than $24 million of Series B corporate equity led by VoLo Earth Ventures and $130 million of debt financing led by Goldman Sachs. Microsoft Climate Innovation Fund and Credit Suisse both joined the equity round.

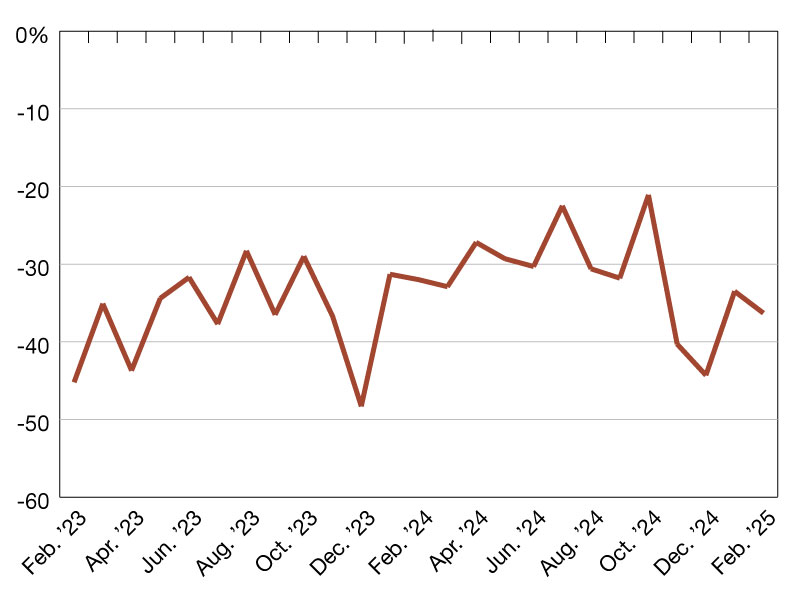

For now, market forces seem to be doing their Darwinian duty among the niche firms. Of course, there are always macroeconomic factors to consider. A downward turn in the economy, or increasingly high cost of capital, is always a hindrance to some extent. And climate tech may already be feeling the impact of an uncertain economy—in 2023, funding for climate tech start-ups decreased to 2018 levels, PwC said in its report.

“Every downturn sees risk off in venture capital, risk off in funding,” said Grinis. “Those that are further down the speculative nature of the curve, they may experience drying up of funding. Those that are not, I think the capital will be there. Do I think that a downturn could hurt the more speculative technologies? 100 percent.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.