Why CRE Insurance Challenges Are Intensifying

Strategies for finding coverage when demand far outstrips supply.

Commercial real estate discussions of late have largely centered on rising mortgage rates, plunging investment sales, declining values and troubled loans. But for asset owners and investors, the ability to find and afford property insurance is becoming increasingly daunting.

That’s especially true in regions that have suffered massive damage and hundreds of billions of dollars in claims losses from hurricanes, wildfires, flooding and other extreme weather events over the past few years. In some cases, the losses have driven insurance companies out of business and carriers have exited riskier markets. As a result, insurance costs have skyrocketed amid “hard market” conditions–insurance demand that greatly outstrips supply.

Early this year, for example, insurance brokerage HUB International and insurance company Swiss Re launched a comprehensive coverage program for shopping centers. The initiative aimed at filling a hole in the market as a result of carriers pulling back from retail assets due to high vacancies, dark anchor tenants, losses suffered during the George Floyd riots and organized looting in some cities, explained James “Chip” Stuart, leader of HUB’s real estate specialty practice in Los Angeles.

But the program dissipated after Swiss Re reorganized and eliminated some business lines following a plummet in net profits in 2022. HUB plans to relaunch the program with Archer Insurance.

“It’s hard for people to understand, but there are not that many insurance companies eager to write new business, especially in the property arena,” Stuart remarked. “The competition is way down right now, and we’re seeing a lot less insurance for a lot higher prices.”

Danger Rising

The situation is creating potentially adverse consequences for property owners, who face default if they fail to meet insurance requirements demanded by lenders. Plus, higher insurance costs could eat into their net operating income, and passing them onto tenants may yield similar hardships for those businesses.

Despite the turmoil, investors are not yet avoiding areas exposed to higher weather risks, as developers of research, data and manufacturing facilities remain active in all regions observed Barry LePatner, a real estate construction adviser in New York. Still, scrutiny is increasing.

“Lenders are the ones who do due diligence on risk, and they are paying much more attention to developers who are building in areas affected by climate change,” he declared. “But as long developers can make a deal pencil out, they will build in those areas.”

If the frequency and severity of weather events witnessed over the last few years continues, however, cost pressures could become too much to overcome, suggested Cindy Barreda, a senior managing director with Trimont REA, an asset manager of complex credit circumstances for real estate lenders and investors globally.

“While investors may consider how much capital they’re willing to place in any particular region, we haven’t seen anyone pull out of a deal because it’s a difficult insurance zone,” she added. “But it doesn’t mean it won’t happen.”

Storm Surge

Tracking climate and weather catastrophes that cause at least $1 billion in damage, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reported that 18 separate events in the U.S. in 2022 cost an inflation-adjusted $165 billion, the third highest amount since 1980. The first seven months of 2023 already eclipsed the 2022 pace, with 15 separate $1 billion disasters, and the Maui wildfires in August will add one more. The average number of $1 billion catastrophes since 1980 is 8.1 a year, according to the agency.

“It seems like the volatility of weather events is worse than it ever has been,” said Danielle Lombardo, chair of the global real estate practice for Lockton Cos. in New York, who participated in a recent insurance webinar hosted by Berkadia. “Lenders, real estate owners and insurance carriers are trying to get a handle on what the new normal looks like so that they can continue to transact with budget certainty.”

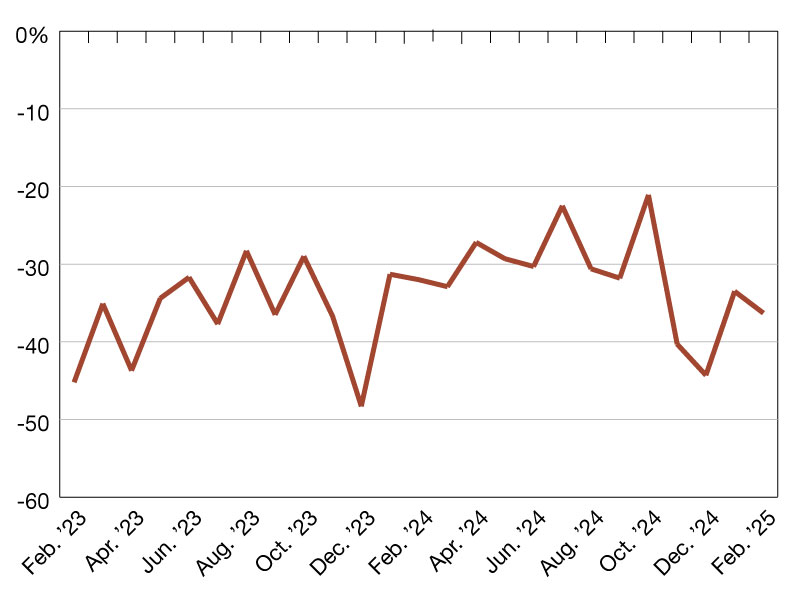

To adjust to the new normal, insurance companies and reinsurers–insurance for insurance companies–have dramatically raised their rates. Traditionally, the cost of property insurance rose by 2 to 3 percentage points a year, but since 2017, the rates have increased an average of 7.6 annually, and they spiked an average of 17 percent midway through 2023 compared to a year earlier, according to Moody’s Analytics CRE.

What insurance carriers have to pay reinsurers is driving those price increases. Reinsurance companies have increased rates 35 percent this year, according to the recently updated Buy Carpenter U.S. Property Rate on Line Index. That represents the largest increase in prices in 17 years.

Some of the increasing expense is impacting how insurance companies view replacement costs, as construction materials and labor have become more expensive. Typically, insurance companies would base a premium on the value of a property—call it $100 a square foot—but replacement cost would be $300 per square foot. Now, carriers are charging much higher premiums that reflect the replacement cost, noted Stuart.

“It’s an advantage to both the insured and the insurance companies to get the replacement cost right,” he stated. “But the hesitation that the insured have is, ‘What’s that going to do to my premium? Triple it?’ And yes, it does go up quite a bit.”

What’s more, insurance companies are pegging deductibles to replacement cost, observed Fred Meno, president & CEO of asset services for Woodmont Properties, a Fort Worth, Texas-based retail developer, brokerage, leasing and management firm. In Texas, a hail deductible of, say, $25,000 per claim in past policies now could be 3 percent of replacement cost value. So, for a 300,000 square foot building worth $300 per square foot, that deductible is now $2.7 million.

“That’s a huge swing,” Meno said. “Landlords may have an option to buy that deductible down, but it’s still incredibly expensive.”

Seeking Solutions

The hard market also puts borrowers at risk of running afoul of loan requirements that typically include carrier rating and coverage minimums. When it’s time to renew a policy, property owners may find lower-rated companies as the only option, or they may not be able to afford the coverage.

“This could be a big tripwire,” Meno pointed out. “Property owners need to get out in front and begin negotiating with their lenders and educating loan officers about what’s going on rather than waiting until they get a proposal and realize they’re going to be in default.”

In addition to communicating with lenders, property owners should take proactive measures, including hardening buildings by adding ember-resistant screens to slow fire, adding sump pumps for floods or strengthening roofs to withstand hail. But some of those strategies may be physically and financially impractical except during new construction, Barreda said. And even then, they may not have a great impact on premiums.

Alternatively, property owners with the financial wherewithal can create their own captive insurance company or pursue a junior version of self-insurance, said Lombardo in a follow-up conversation with CPE. Insureds who are paying $8 million for a policy that covers the first $10 million losses, for example, may determine that it makes more sense to keep that $8 million on their balance sheet as a reserve for losses.

“The challenge is that you could have 10 $10 million losses per year, and you would have to pay them. But there are options to cap your downside,” she noted. “The broader idea is that property owners are looking into alternatives to take on more risk because the market is so volatile, and rates keep increasing.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.