Why Risk Retention Might Not Be So Bad for CMBS, After All

By Paul Fiorilla, Associate Director of Research, Yardi Matrix: After a year of fretting over the damage that risk retention rules would do to the CMBS market, the first deal that used the structure was a home run for the issuers. Now what?

By Paul Fiorilla, Associate Director of Research, Yardi Matrix

After a year of fretting over the damage that risk retention rules would do to the CMBS market, the first deal that used the structure was a home run for the issuers. Now some in the industry are wondering: Will the regulation ultimately do more good than harm?

The debate surrounding risk retention—a requirement that issuers of CMBS retain 5 percent of the securities sold—has centered on just how negative the impact would be. The laundry list of concerns focused on whether it would dry up capital to buy the first-loss classes and whether it would make securitization programs less competitive by increasing the cost of lending.

Yet when the first glimpse of risk retention came into view this month, the results were surprisingly positive. Although risk retention is not mandatory until the first quarter of 2017, Wells Fargo, Bank of America and Morgan Stanley teamed up to securitize an $870.6 million pool of loans in which they retained 5 percent of the bonds.

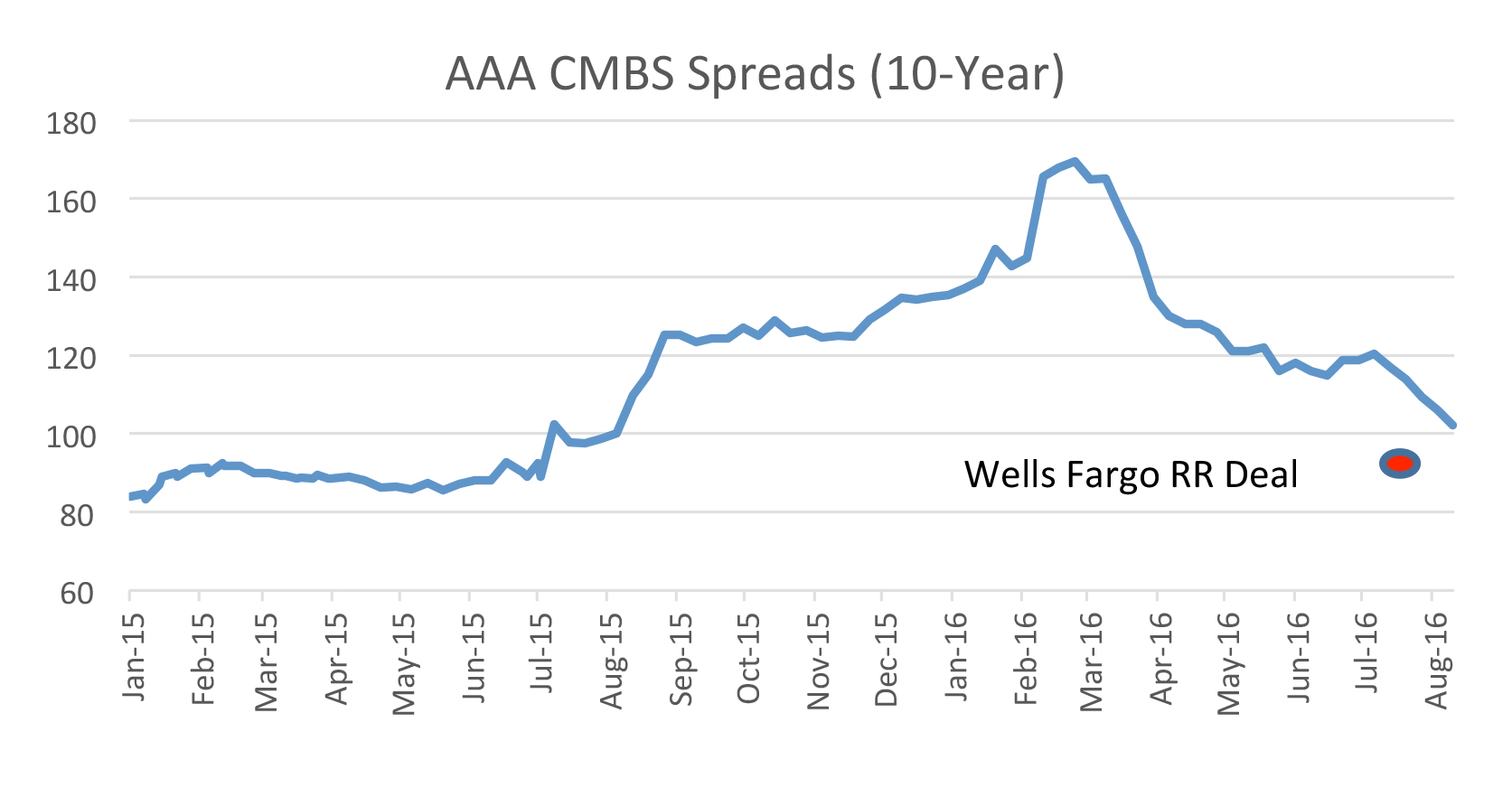

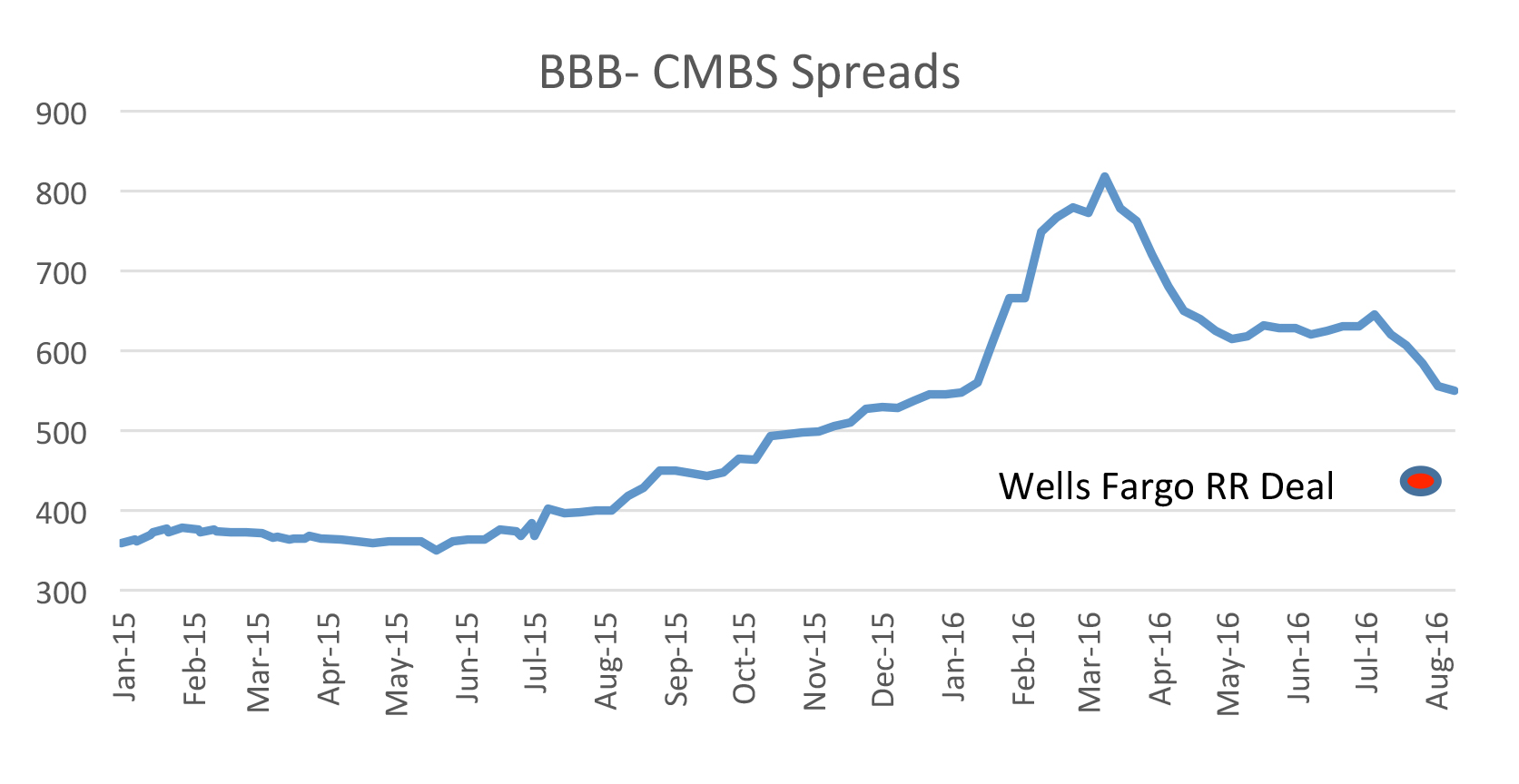

The Wells Fargo-led transaction, which priced on Aug. 4, was extremely well received by investors. The 9.9-year triple A-rated class was priced to yield 94 basis points over swap spreads, 15 basis points less than market spreads a week earlier and nine basis points less than a comparable deal that priced the following week, according to “Commercial Mortgage Alert.” The risk retention deal’s triple-B-minus class was priced to yield 425 basis points over swap spreads, compared to market spreads of 584 basis points a week earlier.

There are various theories as to why the deal priced so well. One is that CMBS issuance has been thin in recent months, so investors were starved for paper to buy. Another is the quality of the collateral: Because the deal was the first of its kind, the issuers were keen to make sure the loans in the pool were pristine. Even granting those conditions, however, it is clear that investors like the idea of banks “eating their own cooking,” so to speak, and they paid a premium for that comfort.

Vertical vs. Horizontal

The key to making the deal work was the “vertical” structure, which means that the issuers retained 5 percent of each class in the transaction, a total of $43.5 million. In order to get more favorable capital treatment, the banks created a synthetic class that enabled them to classify the collateral for accounting purposes as whole loans rather than securities. That whole-loan treatment allows the banks to set aside considerably less capital than they would have to to hold securities, which in effect makes the deal more profitable.

Since 93 percent of the transaction carries an investment-grade rating of triple-B-minus or higher, the amount of collateral held by the banks that is in danger of defaulting is fairly small. What’s more, the banks stand to collect regular income for the collateral that they hold.

When risk retention was first contemplated, the market largely assumed that a different structure—known as “horizontal”—would be the most common. Under a horizontal structure, the bottom 5 percent of the deal would be sold to a “B-piece” buyer. CMBS issuers have historically sold the most junior tranches to B-piece investors. These classes are sold at high yields, typically between 15 and 20 percent, but also carry the highest risk because they bear the brunt of defaults.

A big drawback to the horizontal structure is that B-piece buyers typically purchase less than 5 percent of the deal structure, while the risk retention regulations prohibit the owners of the 5 percent strip from selling the bonds for five years. The concern was that forcing the B-piece buyer to purchase higher-rated classes they do not want and then prohibiting them from trading the positions would dry up demand, or at the very least drive down prices for B pieces to the point that it would become prohibitively expensive for the securitization programs.

Using the vertical structure eliminates most issues with the B piece, as the junior bonds (minus the 5 percent strip retained by the issuers) can be sold in the normal process. The Wells Fargo team sold the junior classes to Rialto Capital at a reported 17 percent yield. What’s more, no matter what structure is employed, the number of active B-piece buyers in the market has allayed fears that there would be a shortage of capital to buy junior bonds under risk retention.

Only the Beginning

Even though the first risk retention CMBS transaction was a success with the vertical structure, it’s far too soon for the market to celebrate. For one thing, bank examiners have yet to rule on the whole-loan accounting treatment employed by the banks. If that treatment is ultimately disallowed, it would make the vertical structure less economical.

Another issue is that the vertical structure requires banks to hold loans on their balance sheets, and eventually they could get to the point where they are full of commercial mortgage holdings and cut back on lending. This might not be a big issue with giant money-center banks such as Wells Fargo and Bank of America but could be with midsize banks and specialty lenders that have smaller balance sheets and less capacity to book loans.

As the CMBS market enters uncharted waters, expect a large amount of experimentation and deals with many different structures—be they vertical, horizontal or “L-shaped,” which is some combination of the two.

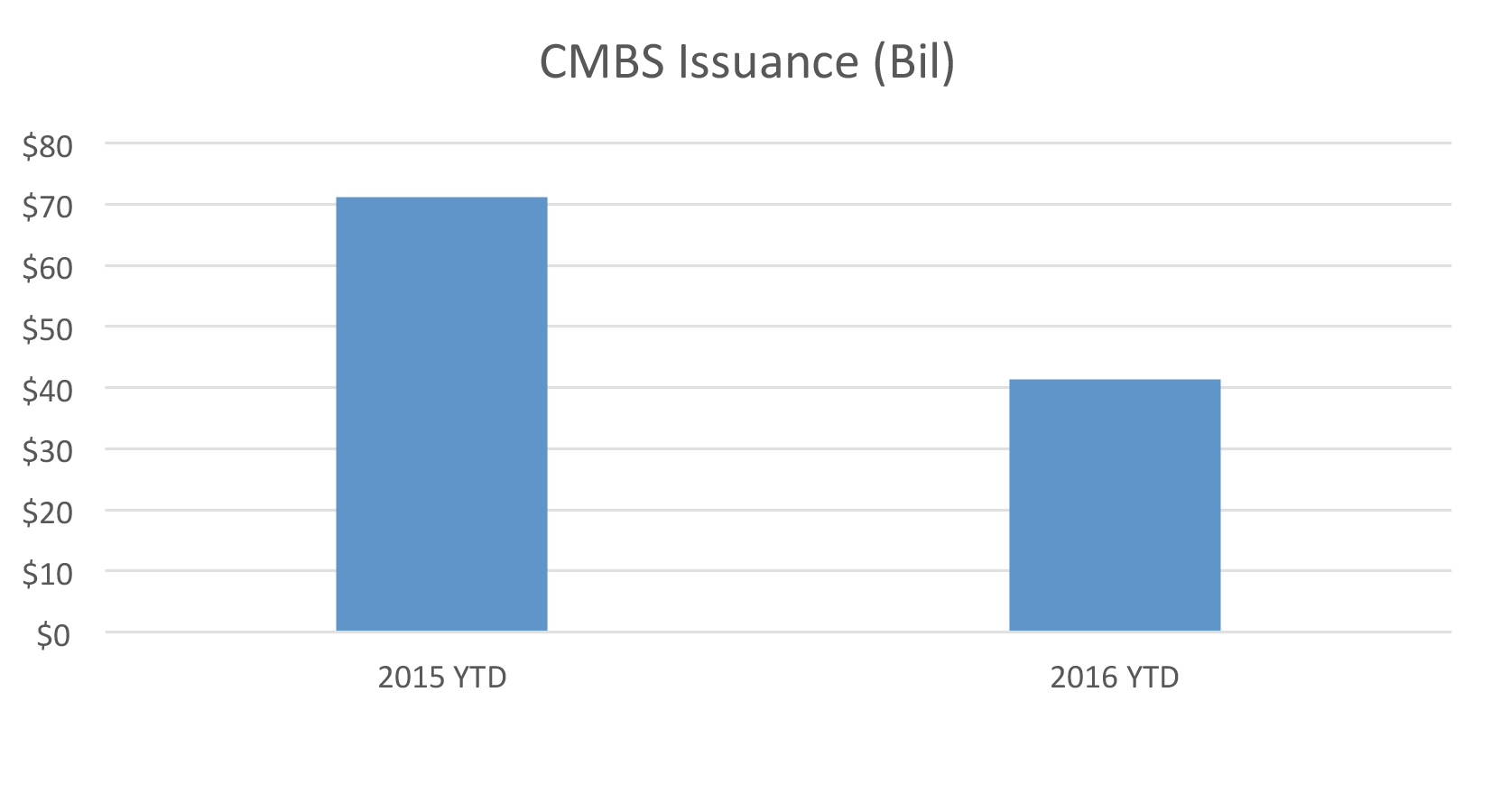

Even so, however, the fact that the first risk retention hurdle was cleared without a hitch is encouraging to a market that has struggled in the face of a host of new regulatory burdens and pricing hurdles. Through mid-August, CMBS issuance in 2016 was only $41.4 billion, down 44 percent from the $71.2 billion issued during the same period in 2015, according to CMA.

If CMBS prices fall as a result of regulations that include risk retention, some fret that the market will find itself permanently unable to compete with banks and life companies. So at least for now, the market can exhale and plan to get back to business.

“The vertical structure makes a lot of sense for larger issuers, especially those with a large balance sheet,” said Tom Fink, a senior vice president at analytics firm Trepp. “It is as close to business as usual as you can get.”

Some investors are even more positive about the impact of the vertical structure, saying that it will force lenders to write better loans that will make the product more popular with investors. Plus, the banks will make money on the portion of the deal that they hold, in what will amount to a win-win situation.

“Banks will find a way to hold the loans with lower capital costs. They will do more business, deals will get larger and they’re not putting much capital at risk. It’s positive across the board,” said one veteran investor. “The industry is going to come to love it.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.