With All That Dry Powder, Office Will Have Its Day

The capital supply has "sparked a manic race for suitable investments," according to John Kevill of Avison Young.

With COVID-19 largely (hopefully) in the rearview mirror, capital is pouring into real estate funds at a level comparable to pre-pandemic levels, and even exceeding that for certain property types.

The investment strategies being pursued by much of this capital will be different than in years past, and the sheer magnitude of the increased focus on some deal types will drive pricing increases, and in many cases it already has. Investors quite simply are making bets on a future that in many ways won’t resemble the past.

Unlike the Great Recession in 2009 and 2010, there has not been a notable degradation of investors’ capital bases. People have money, and given the period of volatility the market has experienced over the past year and a half, real estate makes sense to a wider audience of investors as a more stable place to park money. The capital supply has sparked a manic race for suitable investments, compressing capitalization rates, driving pricing up and testing the fortitude of investors as they aggressively push assumptions.

What’s fascinating is that many assumptions are being made with tremendous market uncertainty as the Delta variant creates near-term issues, and it still remains to be seen how COVID-19 has affected the long term use of real estate. It will be interesting to monitor the strategies undertaken by investors to park their capital and how they shift based on what realities emerge.

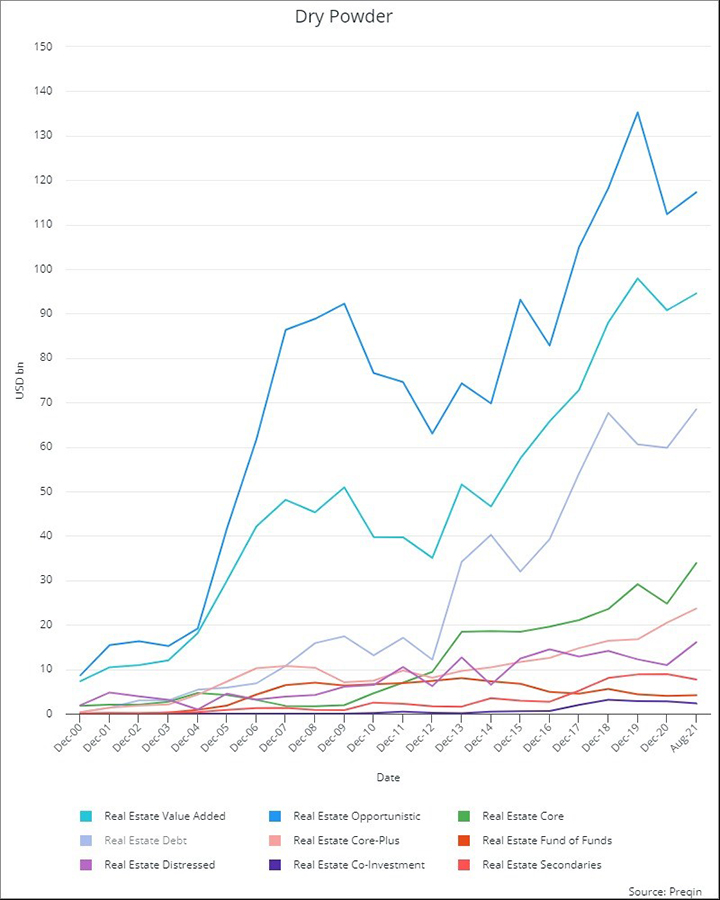

From 2011 to August of 2021, the amount of dry powder targeting U.S. real estate has increased 139.2 percent, according to Preqin, with the current figure totaling $231.8 billion. Most of this is focused on opportunistic (29.9 percent) followed by value added (28.3 percent) and debt (21.7 percent) investment opportunities. All of this money needs to go somewhere.

The phenomenon being observed with regard to cap rate compression—sometimes called “pancaking”—occurs when cap rates across markets, whether big or small, are essentially the same. An apartment building in Manhattan trading at the same cap rate as one in Baton Rouge? How does this happen? In addition to rising prices, several factors also contribute to this. The cost of debt capital and populations seeking a lower cost of living combine to present a lower risk profile for many markets that were previously deemed less desirable.

It has been well documented that industrial deal volume has exploded, with industrial transactions from January to May increasing 18 percent relative to their figures from 2015 to 2019. With the rise of e-commerce bolstered even further by stay-at-home mandates, retail sales have shifted toward a direct-to-consumer model by way of warehouse, causing a much-accelerated interest in industrial properties, primarily in accessible areas.

Industrial properties are drawing a premium from investors who have seen both an influx of tenants trying to fulfill the increased volume of online orders, as well as those who have observed the change in supply chains since the onset of the pandemic. Again, as in multifamily, markets that were once seen as riskier are now on par with those that have been more “core,” as there is a perceived permanence to these shifts.

There has also been an increase in office investing, but it remains a wild card in the longer term. The days where large-scale real estate investors were seeking core returns in downtown office towers may be well behind us for a long time. Many office buildings struggle to fill vacant space, and with the future of work being a heavily debated subject, traditional office investors have deviated and diversified their portfolios accordingly. While workers have begun to return to the office, it is certainly not universal. A comparison of weekly foot traffic from July 2019 to July 2021 shows an over 70 percent decline during that period. That is dramatic, and while common wisdom is that there will be a return to the office en masse after Labor Day, we have started to see businesses push that date back, due to the Delta variant.

Of course that complicates the underwriting of many office investors, as they need some proof that things are returning to normal or some indications of what the “new normal” might be. To date in 2021, $33.9 billion of office deals have closed, representing an annualized change of -42.3 percent relative to the prior five-year average dollar volume, while asset pricing has decreased by 27.1 percent in CBD markets throughout the country. In an unusual market twist, we see cap rates in CBD markets 25 bps higher than in suburban markets nationally. Our expectation for the near future is that the amount of capital targeted for office investment will drive velocity and it won’t take much proof of concept to drive investors into the market. The $231.8 billion needs to go somewhere.

John Kevill is principal & president of U.S. Capital Markets at Avison Young.

You must be logged in to post a comment.